© Yi-Chun Wu. (Click image for larger version)

Jérôme Bel

The Show Must Go On

★★★★★

New York, Joyce Theater

21 October 2016

www.jeromebel.fr

www.joyce.org

Jérôme Bel has been called many things, from conceptual artist to choreographer. If art is supposed to put a mirror up to humanity and at the same time challenge convention, Bel is certainly an artist, and one who has also referred to himself as a “philosopher of dance.”

Bel has been busy this month. His work Gala recently had its London premiere, and in New York, he is a focus artist at the Crossing the Line Festival, which is presenting The show must go on at the Joyce, the eponymous work Jérôme Bel at the Kitchen and Artist’s Choice: Jérôme Bel MoMA Dance Company – a work commissioned specifically with the collaboration of MoMA and its staff – at the museum. Bel’s work has instigated lawsuits and the Paris premiere of The show must go on sparked outrage, while in New York it received a warm reception, and got a Bessie Award in 2005.

© Yi-Chun Wu. (Click image for larger version)

The show must go on, named after the Queen song, is an entertaining meditation on the human response to music – the emotional and the visceral – and dance itself. In keeping with many of his other works, Bel uses both amateur and trained dancers (in this case, they were local; in London he has at times worked with Candoco) and a healthy dose of humor to get his points across. The mixture of dance experience on stage creates a temporary reality not unlike the dance floor at a wedding. Bodies of all shapes, sizes and capabilities move and groove, dancing to the beat of their own drummer. By re-creating this environment and placing it on the stage, Bel elevates and allows for examination of the very primal connection we have to music and rhythm. The communal power of music is apparent on two levels: that of the intuited, human response to any beat or musical phrase (almost all of us respond to music, whether we are on the beat or not is another matter), and that of the instant sense of community which is created through common knowledge of a song. By using pop tunes for this evening-length work, Bel’s work strikes a universal chord. Even if you can’t stand some of the tunes, you would have to have lived in the bottom of a well for the last several decades not to have heard them.

Today we rarely experience music for the sake of music. Music is everywhere and nowhere at once, demoted to the place of carpet or wallpaper: something deemed a necessary part of our overall environment but which through its overuse has become invisible. At what store, restaurant, gas station or airport are we not harangued with music? Silence and its tired bedfellow, music, are rarely truly heard in modern society. We don’t go to see three bands and watch them all perform at once. Music requires if not complete silence then monotasking, one artist following another per stage. Silence acts in the service of music and is required to “hear” music, and Bel does a wondrous job of making us realize the necessity of the two working together. He also makes us realize how increasingly rarified it is.

The most obvious, simplest and wittiest way he achieves this is through Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sounds of Silence.” The stage is bare, no performers, and the DJ clicks play on the CD player. Whenever the lyrics approached the first syllable of the word “silence,” the DJ fades out the music. He brings it back, and fades it each time the word repeats. The audience laughs at the joke, and it is funny, but it is also a reminder of how much better you hear, and can listen to music, when contrasted with quiet.

© Yi-Chun Wu. (Click image for larger version)

While Simon and Garfunkel enabled Bel to make a joke about silence and sound, he sets the entire tone for The show must go on by utilizing the “silence” of movement. The work opens with a dark stage and a dark auditorium. A DJ is set up facing the stage in the first row of the theatre, with a very small soundboard.

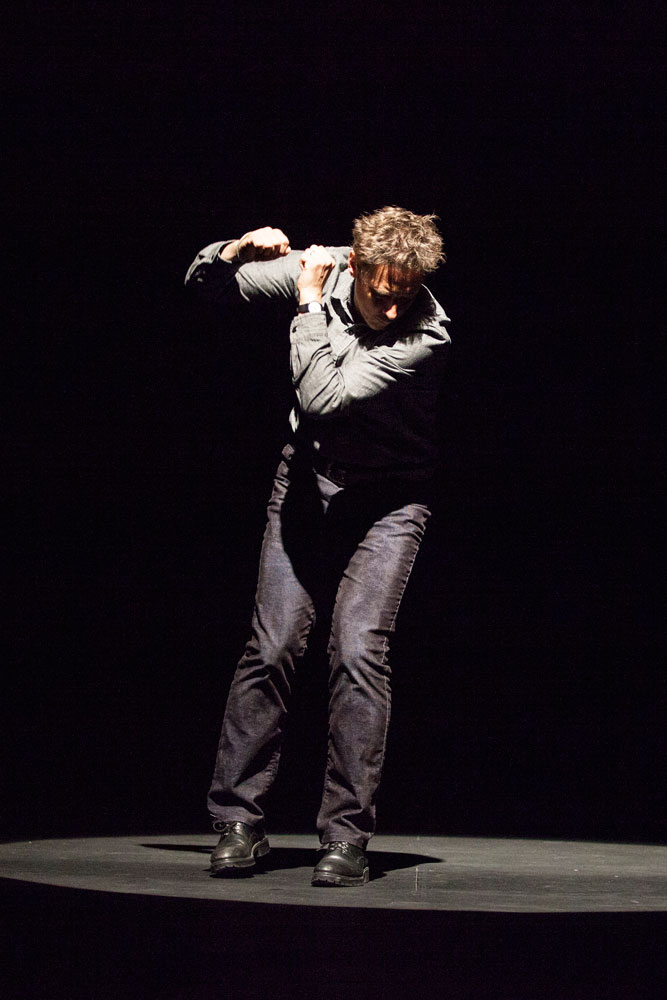

Excerpts of Bernstein’s “Tonight” from “West Side Story” are played. Everything remains pitch black. We hear the DJ click and flick switches. The gospel-like strains of “Let The Sunshine In” plays. The stage lights eventually grow brighter and brighter; the sunshine is coming in. The DJ methodically opens the CD player, takes one CD out of the tray, puts it aside, opens a jewel case and puts the new CD in the tray, the audience having full audibility of the plasticy clicks and taps. The DJ’s methodical choreography becomes a running joke throughout the piece. He could use a playlist, the songs could all be recorded on one CD, or played off of a laptop, or he could mix tunes, but with earnest dedication he plays one song after another all on CD. An essential player in the piece, the DJ – who has a moment in the spotlight later on, dancing solo to Tina Turner’s rendition of Mark Knopfler’s “Private Dancer” – is the maestro, frequently putting on and taking off his glasses with a professorial seriousness that often sparks laughter.

The Beatles’ “Come Together” starts playing and eventually a group of bodies come onto the stage. They do nothing but stare at the audience for the entirety of the song. The audience can’t help but laugh. Bel thwarts expectations by putting bodies on stage that do not move, or by playing music with no other visible activity occurring. When was the last time any of us sat in a room and did nothing but sit still and listen to a song or an album? As we know most people experience pop music in department stores and on their smartphones, while commuting through the urban landscape (Bel reminds us of this in a not-so-silent disco sequence wherein performers groove to their iPods/iPhones and occasionally belt out the lyrics to very different tunes). Overall, the pauses of activity in Bel’s work force us to be attentive to the music.

David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” follows The Beatles. The performers still stand, unmoved. The audience laughs again. It is only when Bowie sings the actual lyrics, “Let’s Dance,” that the performers start moving, each in their own way, a little shuffle here, a hip jut there, a booty shake and head nod over there. They stop moving at intervals, and start again whenever Bowie says “Let’s Dance.”

© Yi-Chun Wu. (Click image for larger version)

“I Like to Move It,” the seminal club track by Reel 2 Reel (legendary DJ and producer Erick Morillo and Mark Quashie), comes on next and the performers take the audience on a ride of wild abandon. Everyone on stage dances as if no one is watching: tits come out, there is repetitive humping and pumping, and in general everyone appears to be having a good time. It is absurd and the audience sustains a nearly uproarious laughter. By the end, half the performers collapse in a heap on the ground, and an audience member says with a laconic sneer, “Pick up your sh*t,” as if they’re talking to their hungover couchsurfing friend the morning after, and we all laughed some more.

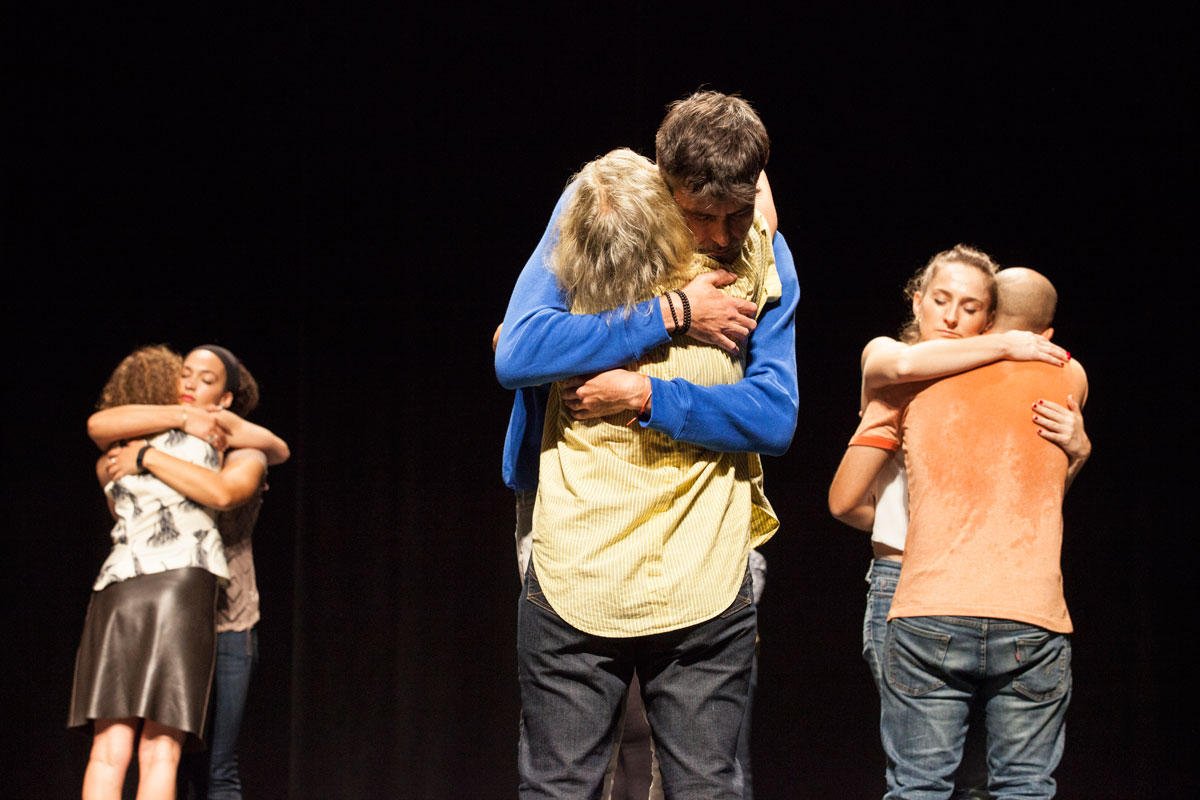

The incorporation of “Macarena” and the earnest dedication the dancers give to the choreography can make The show turns the audience into voyeuristic spectators at a zoomba class. Watching the various ways in which all our very differently shaped bodies move to the same choreography, is a fascinating exercise and is a wonderful celebration of human diversity. In another turn of clever pop culture play, Bel uses Celine Dion’s “The Heart Must Go On,” and reuses the film’s gestures (Kate’s arms out, her waist held by Leo) from one of its most famous scenes to sidesplitting effect, coupling the dancers up into pairs and pitching each “Rose” (not always a female performer) forward at just the right moment, at a 45 degree angle before engaging in a promenade. The witty use of a singular pop culture reference creates community among the audience and the dancers, and across the pit.

If Bel is a philosopher of dance, what is the ultimate motive behind The show? While the play between spectator and performer is constant and may have been a prime motivator in the work’s creation, the biggest take away from The show must go on is its celebration of humanity and our relationship to music and dance – dance as community, dance as expression, dance as cathartic ecstasy. If every club was as accepting as Bel’s stage is towards our diversity, society would be a much more inclusive, happier place. The human body created music, and our relationship to it is deep, instinctive and unifying.

You must be logged in to post a comment.