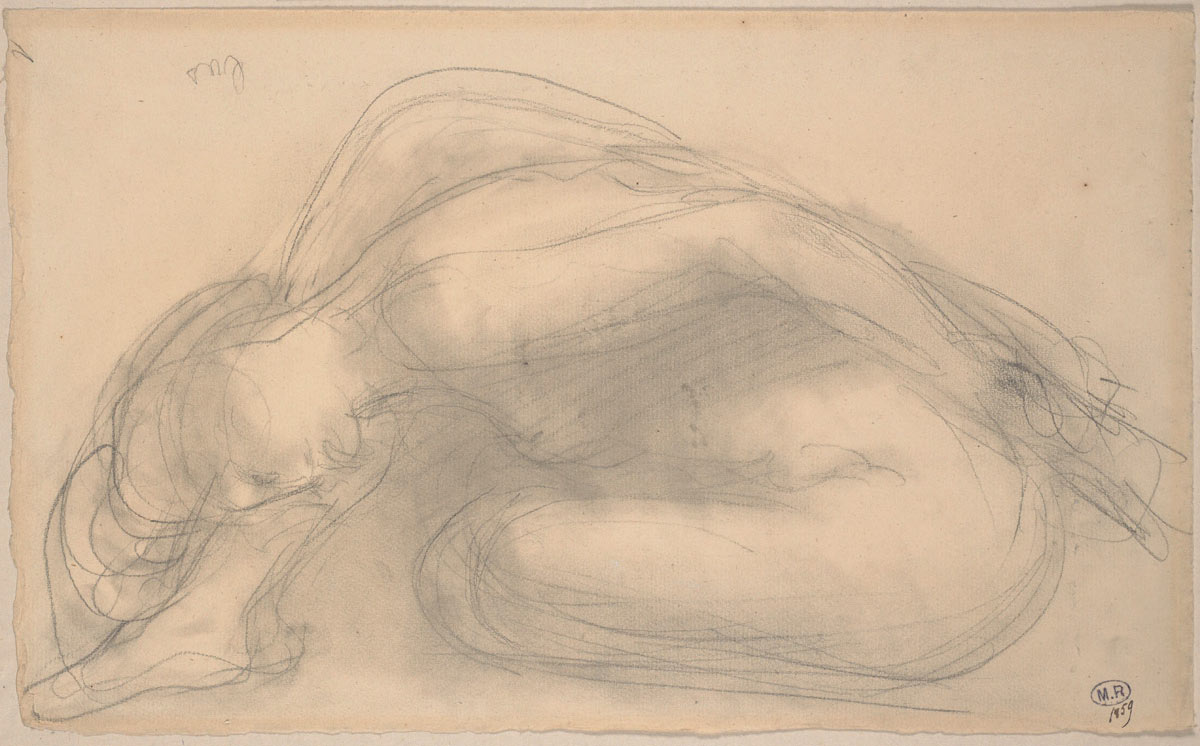

© Musée Rodin. photo: Jean de Calan. (Click image for larger version)

Rodin and Dance: the Essence of Movement

London, Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House

Runs to 22 January 2017

★★✰✰✰

courtauld.ac.uk/gallery

The title of this scholarly exhibition is a misnomer. Though Auguste Rodin was fascinated by trying to capture movement in a still form – drawing or sculpture – the figures on display are static. Apart from sketches of dancers at the start of the exhibition, the statuettes are of held poses. Most are depictions of a female acrobat, Alda Moreno, maintaining limbering positions in the nude. Rodin understood anatomy but not how dancers moved, unlike his contemporary, Edgar Degas.

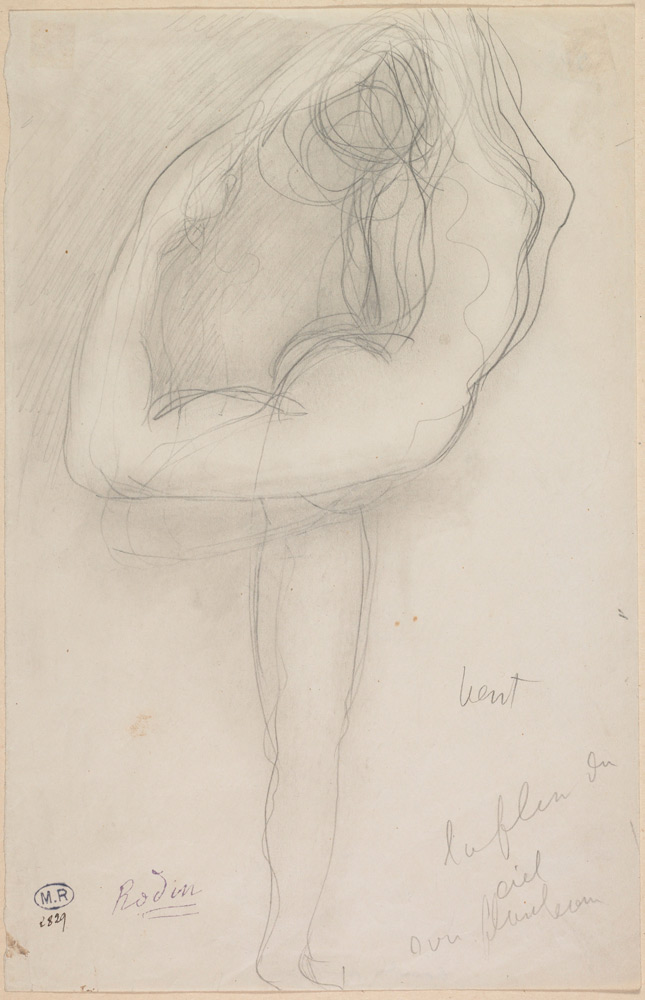

© Agence photographique du musée Rodin – Pauline Hisbacq. (Click image for larger version)

Since Degas had appropriated classical ballet as a subject, Rodin turned to other forms of dance for possible inspiration. He sketched visiting troupes of Javanese and Cambodian dancers who came to colonial and trade exhibitions in Paris and Marseille in 1906. Though the delicate drawings do give an impression of movement, they are unrevealing of oriental dance styles. Perhaps the costumes got in the way.

He failed to record Isadora Duncan’s visit to his studio, probably because she wouldn’t pose for long enough. She objected to his groping her body – or moulding it, as he preferred to say. He did, however, sketch Ruth St Denis’s upper torso and outstretched arms. He made numerous drawings of a dynamic Japanese actress and dancer, Hanako. Was he responding to radically new kinds of dance that freed the body to move in more expressive ways than the formalities of ballet training? Or was he looking for eye-catching shapes that he could use in his sculptures?

He traced over his rapid sketches of Hanako and Alda Moreno, simplifying them into almost abstract outlines. A 1905 cut-out of Moreno, described as Nude Doing a Handstand, resembles one of Matisse’s paper ‘drawings with scissors’, long before Matisse resorted to cut-outs in his old age. The tripod outline could be placed sideways, turned upside down, destabilised. By 1911, Rodin was experimenting with little clay figurines of Moreno in two limbering poses. To preserve them, he had them cast in plaster moulds, which his mould-makers cut into sections. Rodin could thus assemble ready-made limbs, torsos and heads in any configuration he wanted, formed of clay, terracotta or plaster.

© Musée Rodin, Paris, France. (Click image for larger version)

These maquettes, shown only to his close friends and supporters, were labour-saving try-outs, a private repertoire of sculptural ideas. They are displayed in the exhibition in a glass cabinet in the centre of the room, with nine of the plaster moulds he used in a case to one side. Entitled Mouvements de Danse, the figures are labelled Dance Movement A to I (a precursor of Yvonne Rainer’s post-modern dance, Trio A, 1966). Seen together, the little models look like dancers leaping, leaning, balancing – time-lapse choreography. But inspected individually, each one is weightless, frozen in an artificial pose. A woman with her hands on the ground, one leg elevated in a penchée arabesque, can be upturned so that so that she is raising the other leg, her hands above her head. A figurine lying on her back, head tucked into her shoulder, leg held by her chest, can be suspended by a support so that she appears to be skipping, defying gravity.

© Musée Rodin, Paris, France. (Click image for larger version)

Rodin was not depicting dancers in movement so much as experimenting with poses taken by a naked acrobat, mostly in positions that exposed her genitalia as overtly as possible. No wonder the figurines were never exhibited in his lifetime, though one of his notorious bronze sculptures, Iris, messenger of the gods, is a full frontal display of female pudenda in a headless figure that could be flying or falling. Like Picasso, Rodin was frank about his obsession with sex.

One of the maquettes of Moreno in an acrobatic position, holding her right foot behind her near her head with both hands (described as Dance Movement A), was scaled up long after his death and cast in bronze. Its clumsiness is obvious compared with Rodin’s delicate sketches of her in the same position. Far more impressive is a small sculpture of Nijinsky, found by chance in a drawer and cast in bronze in 1958. The vigorous, contorted figure of a muscular dancer clutching his left foot in an anatomically impossible position could not have been made from life, though Nijinsky did visit Rodin’s studio in 1912. It is supposed to be Nijinsky in L’Après-midi d’un faune, but the dancer never adopted that knee-hugging position in his controversial ballet, which Rodin had defended in print (in a letter written in his name, subsequently retracted).

© Musée Rodin, Paris, France. (Click image for larger version)

The vital little figurine must have been an impression made from memory – perhaps of Njinsky as the Golden Slave in Schéhérazade. It was never meant to stand upright – the right leg has no foot. Yet it was cast in an edition of 13 by the Musée Rodin, held up on a plinth, some 40 years after Rodin’s death. The Courtauld Gallery owns one of them, thanks to a gift from Lilian Browse in 2006. It’s the only three-dimensional image of a dancer in action in the entire exhibition, and it has nothing to do with the lifeless recycled body parts in the display case.

© Musée Rodin, Paris, France. (Click image for larger version)

To animate the exhibition, a dancer from Shobana Jeyasingh’s company performs on special occasions alongside the figurines doing Dance Movements A to I. Noora Kela, in a flesh-coloured leotard, adopts the same limbering pose as Alda Moreno, holding one leg upraised behind her with both hands. Kela shunts sideways, hanging onto her foot, in simulation of the repeated outlines in one of the drawings of Moreno as she shifted, trying to keep her balance. Kela sinks into a plié (Rodin made a lot of crouched figures) that forms the diamond shape of South Asian classical dance. She links movements together, using the sinuous arm and hand gestures of oriental dance techniques. In the brief performance, Kela gives a sense of what Rodin must have been observing when he sketched and sculpted supple female figures. The results displayed in the exhibition, however, are of more interest to Rodin scholars than dance-lovers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.