© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Wayne McGregor bill: Chroma, Multiverse, Carbon Life

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House:

10 November 2016

Gallery of pictures by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.roh.org.uk

This triple bill celebrating Wayne McGregor’s ten years as resident choreographer with the Royal Ballet reveals the changes in his approach and interests, which have always been eclectic. He has profited from ballet’s extensive vocabulary of steps large and small, enabling precision-trained dancers to move at speed, covering space.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

When he first made Chroma in 2006, he was primarily concerned with the ways in which hyper-supple bodies can be articulated and manipulated. The 25-minute piece is essentially a sequence of duets and trios framed by a rectangle in John Pawson’s architectural set. Dancers stand within it in silhouette, watching aggressively acrobatic encounters until their turn comes. McGregor had worked out how to get his dancers on stage but not how to get them off. After a physically intimate duet, with the woman flung and clasped around the man’s body, the pair simply walk off in opposite directions. Nothing significant has happened between them.

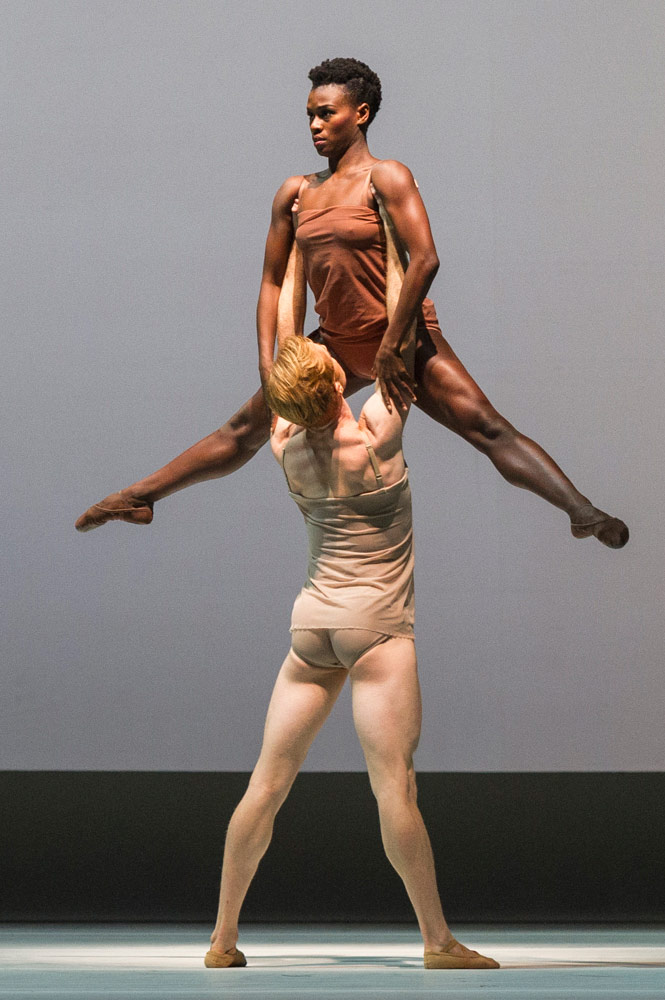

Ten years on, Chroma has become more human, more colourful. Jaqueline Green, a guest from the Alvin Ailey company, extends an imperious hand to Jereboam Bozeman, demanding to be paid attention after his self-concerned solo. Lauren Cuthbertson refuses to be impressed by Jamar Roberts’s sinuous writhing and wrestles with him provocatively. In contrast, Sarah Lamb with Federico Bonelli look like delicate insects mating to Joby Talbot’s tinkling music. All ten dancers come together for a calligraphic battle of flying limbs to Talbot’s urgent Helicopter for full orchestra.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The inclusion of guests from Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, a mainly contemporary dance company like McGregor’s own troupe, shows that his acrobatic choreography can be performed by a range of flexible physiques. (Chroma is in the repertoire of numerous companies.) Not so Multiverse, given its premiere on Wednesday. Its opening sequence could only be executed by super-speedy ballet dancers; later, some of the women are on pointe. McGregor is making a statement about time-shifts, past, present and possibly future.

He accounted for his thinking – and the title – in an ROH Insight talk. There’s also a long article in the ROH programme by his dramaturg, Uzma Hameed. We’re in the realms of cosmology, positing that there may be many alternative universes coterminous with ours, in which events have infinitely possible outcomes. Even in this universe history repeats itself, so that legends of the Flood and Noah’s ark re-emerge, transformed into migrations across the sea by desperate refugees.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

How this plays out in a ballet of three scenes depends on Steve Reich’s music and Rashid Rana’s set design. The commission of a new piece, Runner, from 80-year-old Reich turned out to be too short, at 16 minutes, for a one-act ballet. With Reich’s agreement, McGregor has preceded Runner with It’s Gonna Rain, a two-part vocal work from 1965. Reich had played a recording of an apocalyptic sermon by a black Pentecostal preacher on two separate tape machines, not completely in sync. The repeated warning, ‘It’s gonna rain’ (and drown the world), begins in unison and then goes in and out of phase, rendering it barely comprehensible. Ear-splittingly amplified in the Opera House, the threat becomes a howl.

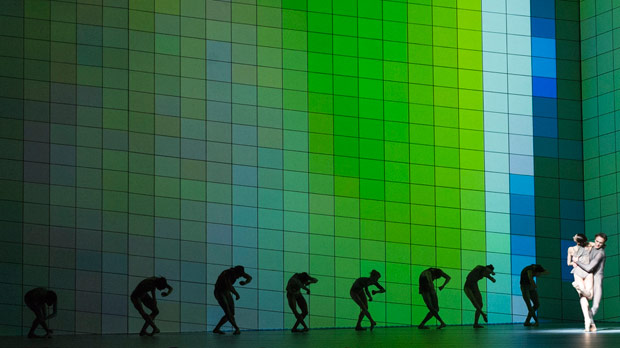

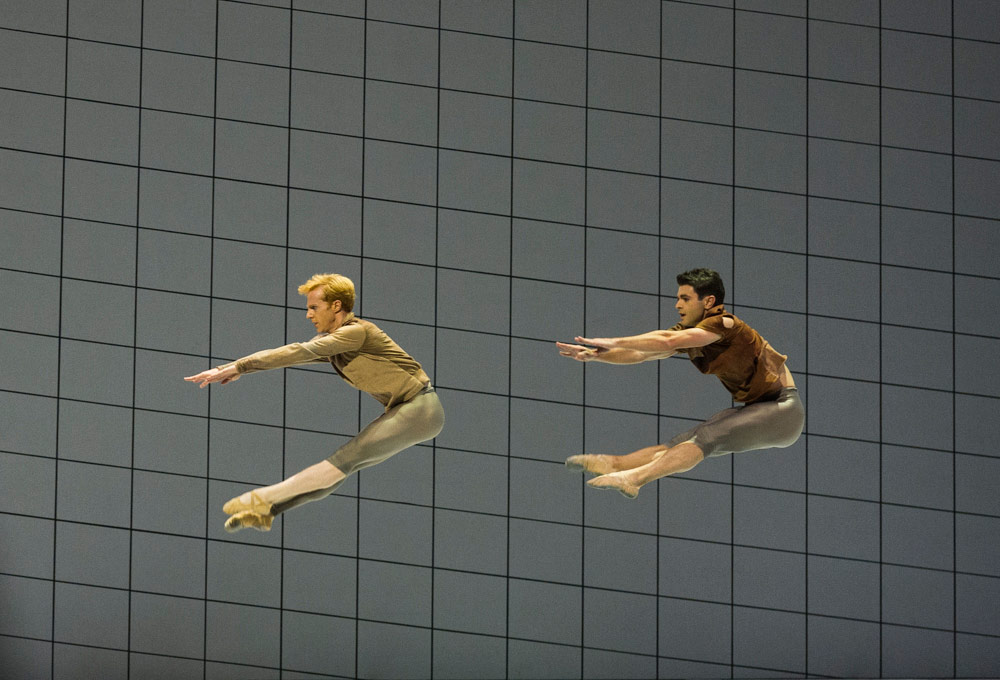

Rana’s set is a V-shaped cell, one wall longer than the other, covered in a grid pattern repeated on the floor. Two men, Steven McRae and Paul Kay, begin in unison and alternate in being leader and follower in overlapping canon formations, reverting at times to unison. Balanchine employed the same contrapuntal device for two men in Agon, though he didn’t sustain the sequence for as long as seven minutes. McGregor’s choreographic demands are less intricate than Balanchine’s – pacing, jumping, spinning, skipping, without the need for interlocked fifth positions – but they require considerable skill, stamina and concentration. Kay and McRae succeed in making their ‘phasing’ look like a gambit by companions rather than a purely technical feat of timing.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

In the next scene, the second part of It’s Gonna Rain, Reich used another extract from the sermon about the rising floodwaters, making the multiple looped phrases frantically incomprehensible and almost unbearable. A photomontage by Rana is projected, all too briefly, onto the longer wall. It is (I am told) a rearrangement of Géricault’s 1818 painting, The Raft of the Medusa, a dramatic depiction of shipwrecked sailors clinging to an overcrowded raft. The fragmented images assembled on the grid pattern are the visual equivalent of Reich’s spliced tape recordings.

A cast of 14 refugees enter in a frightened huddle, staring up at the walls (or heavens) and holding onto each other. There’s a sense of panic and disequilibrium when they break away. Some assert themselves in solos and grappling duets, others are intimidated. Two of the women, Lamb and Marianela Nunez, are on pointe – perhaps a reference to the earlier culture of the painting and balletic tradition. A dark shadow slowly descends on the grid. When it blacks out the stage, figures with torches arrive: rescuers or ruthless people traffickers?

The third section is set to live orchestral music that Reich based on different note durations. Runner seems to promise endurance and maybe salvation. Coloured lights play across the walls as dancers run, leap and spin. A frieze of pacing figures progresses across the shorter wall, measuring out Reich’s rhythms as duets, trios and quartets unspool in the middle. Though the partnering is as extreme as ever, the women’s legs constantly splayed, the transitions between lifts are far more fluent than in Chroma. Relationships appear to develop, hard to identify as couples keep changing, though evidently emotional.

A protective family grouping emerges, involving Cuthbertson, Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball. But they disperse and most of the cast exit stage left along the bigger wall. By the end, the music pulsing on long notes from the woodwinds, Cuthbertson, Hayward and Maya Magri are left moving serenely in canon. The music runs out but they keep going – into eternity?

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The connections between the three sections of Multiverse are far from obvious, even if you’ve pored over the programme notes. The seven minutes in the middle referring to migrants, and possibly climate change and divine retribution, are opaque; the implications of the final section are too elusive for a conclusion. McGregor and his dramaturg may know what they want to convey about life and the universe(s) but despite the dancers’ efforts, the result is baffling.

Carbon Life from 2012 is an entertaining pop-video extravaganza to end the evening. A band on stage features one of the composers, Andrew Wyatt (the other is Mark Ronson) and a young rapper, Dave, among the seven singers. The lyrics are apparently about love in various forms. Gareth Pugh’s designs animate the setting and disguise the performers in increasingly cumbersome costumes.

© Foteini Christofilopoulou, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

McGregor’s choreography is a collage of references, somewhat similar to Rashid Rana’s montage of other artists’ paintings in Multiverse. Near the start, a phalanx of dancers parades in a drilled sequence of tendus – very Balanchine, very Forsythe. Then come tributes to Karole Armitage’s Drastic-Classicism and Michael Clark’s punk ballet essays in outlandish outfits. Youngsters enjoy themselves but more senior artists, such as Marianela Nunez, Edward Watson and Eric Underwood, could save their energies and their bodies for something more worthy of their talents.

You must be logged in to post a comment.