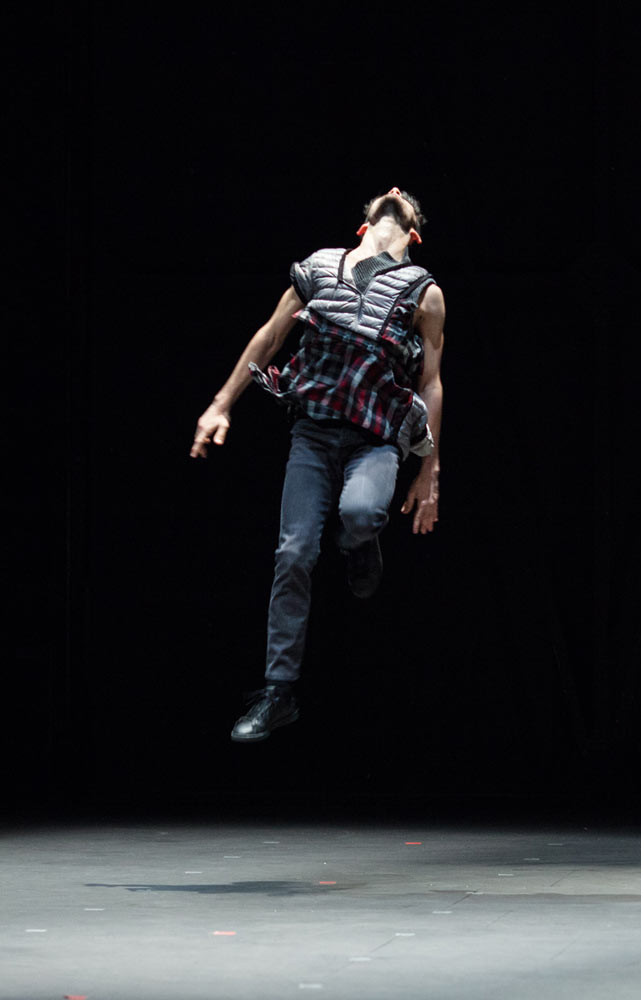

© Laurent Philuppe. (Click image for larger version)

CCN: Ballet de Lorraine

Devoted, HOK Solo Pour Ensemble, Sounddance

★★★✰✰

New York, Joyce Theater

7 Feb 2017

ballet-de-lorraine.eu

www.joyce.org

Fast and Furious

This winter, New York is getting to see more Merce Cunningham than it has in years, thanks to visits from various European companies. It is a sad fact that Europe has always been more supportive of Cunningham than the choreographer’s own country. In March, the Paul Taylor Dance Company will host Lyon Opera Ballet in Summerscape in a tripartite evening devoted to Cunningham, Graham and Taylor. In April, the Compagnie CNDC-Angers, led by former Cunninghamite Robert Swinston, brings a whole evening of works. But the first European visitor is the Nancy-based Ballet de Lorraine, which this week brought the 1975 work Sounddance to the Joyce Theatre as part of its American début.

And thank god they did, because the two works that preceded it – Cecilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud’s Devoted, followed by Alban Richard’s HOK Solo Pour Ensemble – had given a less than riveting impression of the ensemble. The Ballet de Lorraine is a “centre choreographique”; in other words, it supports new creations, which is all to the good. Bengolea, Chaignaud, and Richard are all young-ish choroegraphers based in France. So the company supports home-grown talent.

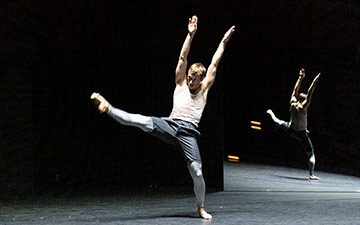

© Arno Paul. (Click image for larger version)

But the devil is in the details. Devoted and HOK Solo Pour Ensemble turned out to be far too similar in concept: movement studies with an accumulative structure, set to Minimalist scores, in which simple movements accrued, while being tweaked and recombined in various ways. Devoted, which was danced sur les pointes by a group of nine women in green leotards, was the more problematic, in that the dancers didn’t look particularly comfortable in the movement. There were wobbles, varying degrees of turnout, a sickled foot or two. It made the dancers look unforceful, almost like students. It was also the most derivative work of the evening, a variant of the formula introduced by Lucinda Childs in the seventies, in which simple ballet steps like spinning and bourréeing and balancing, are repeated almost obsessively until they blend into a kind of mantra. (It was even set to music by Philip Glass, a frequent Childs collaborator.) The palette was somewhat expanded to include undulating torsos, steps in which one leg loped while the other dragged, and, finally, almost gymnastic displays in which dancers jumped up only to land in a split on the floor, with a resounding thwack. The dancers’ faces were painted in fanciful slashes of color. This did little to improve matters.

Albin Richard’s HOK was a step forward, if only because the cast of twelve – now mixed – seemed much more comfortable in its gender-neutral get-up of black jeans, black sneakers, and gray t-shirts. Again, the dancers lined up at the start, only to begin bending their torsos and swinging their arms, to a clanging score by the Dutch Minimalist Louis Andriessen. What was at first done in unison, then broke into a series of variations, with new elements added along the way: walking, running, pivots, circles and bends. There were moments of excitement when the movement seemed to escape its rigid structure and melt into a smear of bodies. But, like Devoted, the changes seemed arbitrary, the surprises not terribly surprising.

© Arno Paul. (Click image for larger version)

What a contrast with Sounddance! From the moment it begins, with a dancer (Matthieu Chayrigues, a standout) rushing out of an opening in a golden curtain at the rear of the stage, the energy rises to a fever pitch. The music, by David Tudor, is like a windstorm. Chayrigues’ solo is fast and furious: within seconds he bends, he pivots, he hops, rises up in relevé, pats the floor in rhythmic footwork, fouettés, nods, tilts. Then another dancer runs out, and it becomes a furious courtship, until a moment later, a third emerges and it morphs into a lively three-way conversation. The dynamic is constantly shifting; there are hints of eroticism (dancers straddling other dancers), aggression (a dancer shaking another dancer by the shoulders) and animal movement (fluttering hands, like feathers). Abstract formations made up of multiple dancers drift like coral reefs in the current, only to dissolve. The sheer profusion of steps, and variations on those steps, is astounding. It’s impossible to take in everything that is going on onstage, until one realizes it’s ok to relax, and just absorb what one can. Cunningham assists us just a little bit by building in moments of repose. We need it, and so do the dancers.

© Laurent Philuppe. (Click image for larger version)

Even so, I often found myself trying not to blink, and holding my breath. Best of all, the work really showed off the dancers; they looked twice as interesting and strong as they did earlier. That’s what good choreography does.

You must be logged in to post a comment.