© Charlie McCullers, courtesy of Atlanta Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

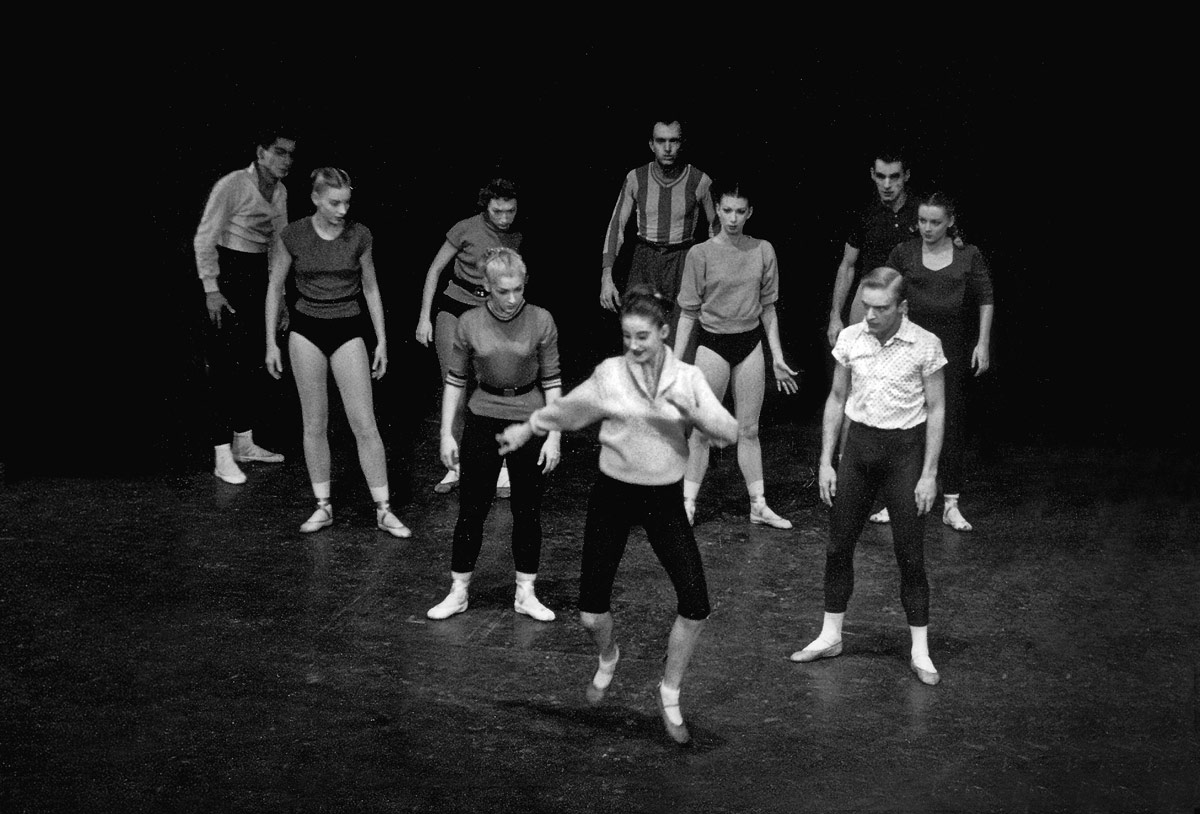

Robert Barnett began studying ballet with Bronislava Nijinska in Los Angeles after he was mustered out of the Navy after the Second World War. He spent a year in Europe with Colonel W. de Basil’s Original Ballet Russe before joining the New York City Ballet in 1949. During Barnett’s nine years at NYCB, he cut a wide swath through the repertoire. George Balanchine choreographed featured roles for him in The Nutcracker and Stars and Stripes; Jerome Robbins, who prized Barnett’s dramatic skills and the unmannered intelligence of his dancing, cast him in every one of his ballets.

In 1958 Barnett and his wife, fellow NYCB dancer Virginia Rich Barnett, left to join the Atlanta Ballet as principal dancers and co–associate directors. Four years later, Barnett became artistic director of Atlanta Ballet, a position he held until 1994.

Photo: Melton-Pippin, New York City Ballet, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

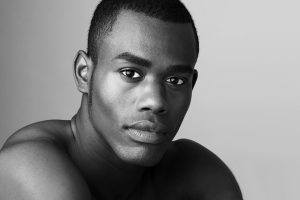

Barnett continues to be in demand as a stager and a teacher. Now 91, he describes himself as “semi-retired,” but he looks anything but retired when he’s working with dancers in the studio. I caught up with Barnett in mid-November while he was in New York coaching for the George Balanchine Foundation Video Archives.

This is a long page and to make it easier to navigate, here is an index so you have the option of jumping straight to what interests you…

Robert Barnett – Topics Covered

Joining New York City Ballet in 1949 and the early years

Frederick Ashton’s Picnic at Tintagel and Bronislava Nijinska

On Joining New York City Ballet in 1949 and the early years

NDC You auditioned for the New York City Ballet in 1949, a little over a year after the troupe was formed. Can you talk about the audition?

RB: I saw the notice in Variety, that they needed a boy. There was an audition on the fifth floor of the City Center. [New York City Ballet was then the resident company at the City Center of Music and Drama, now called New York City Center.] That was in December 1949. I had returned from Europe in April of that year and had gone to St. Louis, Missouri, to do summer theatre, just so I could make some money. I came back [to New York] and I was studying and I was doing terrible TV shows just to make ends meet. I saw this notice and decided I’d go give it a try. I walked in, and there were at least 200 boys in that room. I thought to myself, “Well, you’re either going to get this or you’re not, but you’re going to be aggressive,” so I was the first boy out on everything. All the steps: Learned it and did it. I was the only boy they took. Which surprised me, because I didn’t know they were just looking for one boy. After the audition, they [George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins and Lincoln Kirstein] called me over and said, “You’ve got the job.” And that’s all they said to me.

There was a dressing room, a separate room, in that studio, and I went up and started to get undressed. Jerry walked in and said, “Where are you going?” I said, “Well, nobody told me what to do, so I decided I’d get dressed and leave.” He said, “No, you have a rehearsal.” So I put my practice clothes back on and went downstairs. They were doing a ballet called The Guests, which I’d never seen, didn’t know anything about it. [The Guests was the first work Robbins made for NYCB.]

So they’d already premiered The Guests before you joined …

Yes, I believe they premiered it the season before. They didn’t do it in the original season, the first season [fall 1948]. But I think he did Guests in their second season. Anyhow, I had never seen it and didn’t know anything about it. Robbins did a run-through of the ballet. It just so happened that the girl I was dancing with knew how to drag people through it [laughs]. So she dragged me through it and taught it to me. The next day I came into rehearsal and learned the second movement of [Balanchine’s] Symphony in C. And the next day I was on the stage doing both of them. So that was my introduction to the New York City Ballet.

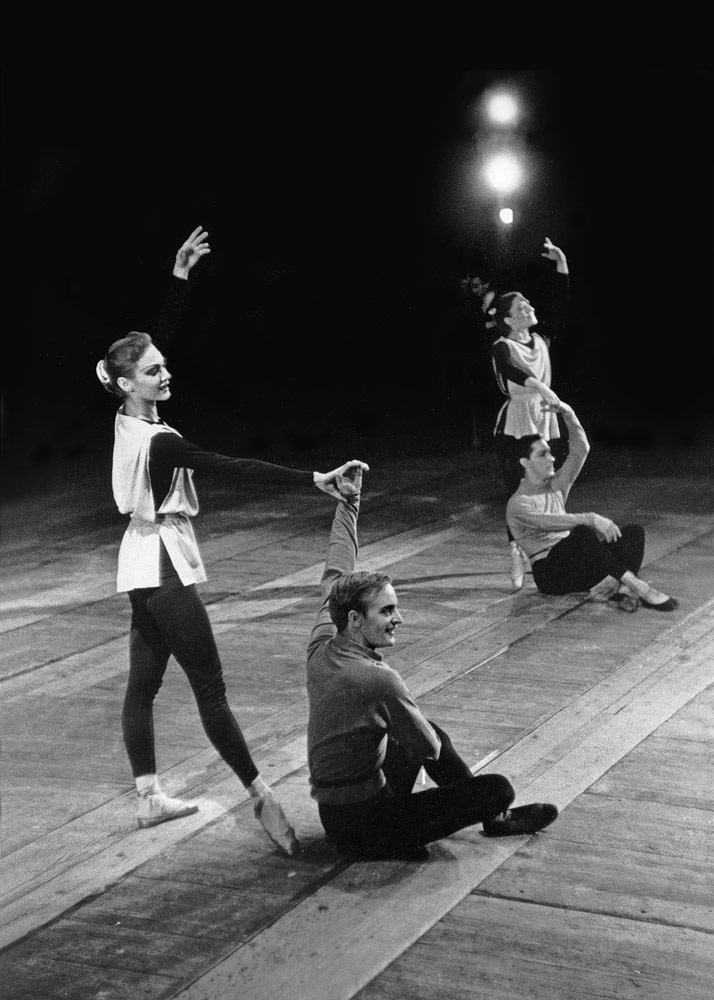

Photo: Fred Fehl, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

Are Candy Cane, from The Nutcracker, and your role leading the “Thunder and Gladiator” regiment in Stars and Stripes the only principal parts that Balanchine created on you?

Yes. I worked a lot with Jerry Robbins and he created things on me, but those were the only things Balanchine created on me. I did a lot of the Balanchine repertoire, but things that had already been choreographed, like third movement in Symphony in C, I danced quite a bit. And I did the first movement of Bourrée Fantasque [1949], which the company doesn’t do anymore, which is really a shame. [The music is by Emmanuel] Chabrier.

The third movement of Symphony in C seems like it would be such joy to dance, and the music is so marvelous. Was it as much fun to dance as it looks?

It was. It’s so lyric, that movement. It’s tricky – like the double chassée turns and all those things – but it had to be done so subtly. Lots of people went at it like they were killing snakes, you know, and that was not the point of it at all – in my estimation. I did it with Melissa [Hayden]. I did it with Patty Wilde. I did it with so many different people.

By “not killing snakes” you mean …

Easy, easy. Just let the technique happen. Don’t push it. That’s what I found wrong with the dancer that I coached in both dances on Monday. [In mid-November, Barnett coached Pennsylvania Ballet Principal Dancer Alexander Peters in Stars and Stripes and The Nutcracker in a film taping for the George Balanchine Foundation Video Archives in New York.] He was hitting it so hard. The steps choreographically are difficult to do. So you don’t need to embroider it, just do the steps as they were meant to be danced. That’s what I tried to get across to [Peters], and I think he got it. I was very pleased, first of all, with the way he worked, because he was so positive and he so wanted to learn. And then the fact that I was really able to get the work out of him so that, at the end, he was doing the correct choreography and he was doing it the correct way musically. It pleased me that he was able to accomplish that.

The George Balanchine Foundation Video Archives, New York, November 2016. Photo by Costas. (Click image for larger version)

I was fascinated not just by the technical things you said – how he should do the jumps and batterie, the importance of keeping his weight forward because of the speed – but also your advice in terms of overall approach and presentation. You said something like, “Be more restrained. Don’t project outward so much.”

What I said to him was, “Just do the steps. Just do the steps. Let the choreography do it. Don’t be pushing it.” I told him at one point: “This is not about you. It’s about executing the choreography. And letting that be the excitement.” He understood that and thanked me for it afterwards when I spoke with him. He said: “You were so helpful as far as the approach is concerned, and it made it easier to dance. “ I could see that happen. I could see him become at ease.

On Stars and Stripes

I know Balanchine almost never told dancers what he thought or why he did things, but do you have any sense why he chose you as the lead for the men’s regiment in Stars and Stripes?

Yes. I think he chose me because of my style of dancing. I was small. I had a big jump. Pirouettes were easy for me. I had studied commercial dancing as well as ballet. And also I learn quickly. All of those things I think were a part of it. And he did the Candy Cane dance for me first [in 1954; Stars and Stripes premiered in January 1958], so he knew how I could move. I think he felt that the movement he was going to do suited me, so he chose me to do it. He never told me why.

Why do you think Balanchine made Stars and Stripes?

I think he did it because Mr. B was very patriotic. He loved this country. And of course when he was married to Maria [Tallchief], he had a lot of contact with American Indians. So I think he did it simply because he felt it would be wonderful to use that music and because he felt very strongly about the United States. I think that’s exactly why, when we went on the tour to the Far East, when we went to Japan [in 1958], a lot of people discouraged him from taking that ballet because it was so patriotic, with the American flag coming up and all of this. Many people thought that would be a slap in the face to the country that we were going to. He said no, he didn’t feel that way at all. He didn’t agree with that premise. He wanted to take it because he was proud of his company being American.

Photo: uncredited, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

Did you and the other dancers agree with him?

I never even thought about it. It wasn’t up to me to think why we were doing it or not, whether there was a purpose. It was up to him as a director, not me as a dancer. I did what I was told.

I don’t understand it when people suggest that the patriotism Balanchine exhibits in Stars and Stripes is jingoistic. I see it as a valentine-to-his-adopted-country kind of patriotism, which is totally different.

Yes… You do a ballet because you feel like doing a ballet. If you have a purpose in mind, so be it. But why make a big deal out of it? I think that lots of times critics overdo that. [He laughs as he says this.] They think that everything has to have a meaning. Why? Everyone used to ask Mr. B, “What is the story of Serenade?” Why did it have to be a story? It’s just a gorgeous ballet. The patterns and everything. And there were some things in it that were brought to mind because of things he had seen or things that had happened within rehearsal. He used those things. But it wasn’t a big psychological drama. It’s just so visibly beautiful, that ballet.

Are you going to do more for the Video Archives?

They mentioned it, but they didn’t say when and they didn’t say what because, as I say, I inherited a lot of principal roles, but the only two things that Mr. B actually did for me were Candy Cane and Stars and Stripes. So I don’t know. Third movement of Symphony in C was done for Herbert Bliss when it was redone for this company, and he’s not around anymore. It was originally done in France [in 1947, for the Paris Opera Ballet]. Palais de Cristal it was called. A lot of people have done the first movement – like Patty Wilde did the first movement. Tanny did the second movement of Symphony in C. And probably was the most beautiful in it. Nobody’s ever danced it like she did.

Photo: Melton-Pippin, New York City Ballet, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

On Tanaquil Le Clercq

Some of the things you told Joel Lobenthal about Tanaquil Le Clercq in your 2013 interview for Ballet Review I’ve never heard before. Details like her putting egg whites in her hair for The Cage to stiffen it so she could arrange it like tentacles, instead of wearing the usual black wig. And putting white makeup on her face and wearing white tights for Swan Lake.

Oh yes. She was a complete artist – and thorough. She knew she was different, so she used that.

Different in what way?

Her body: tall, thin. She had one foot that was slightly sickled. The only flaw that she had. The most beautiful face on the stage you would ever want to look at. And makeup. Just impeccable for whatever she did. It was never the same. She thought about the role. She was a storyteller. I never saw her ever dance anything that I didn’t think she was just absolutely from heaven.

I know she’s a terrific comedienne, and I love her in that 1956 television broadcast of Concerto Barocco for Radio-Canada in Montreal.

The way she moved in Concerto Barocco, that was intensely her. It was almost jerky. But so right for that piece of music.

So that was her idea, not Balanchine’s? She made it look that way?

That’s right. And he allowed her to do it. That’s one of the things which I think fascinated him about her. She was a real artist.

And Jerry Robbins was in love with her too…

Absolutely. And used her beautifully. Like Afternoon of a Faun. It broke my heart that she didn’t do it with Frank [Francisco] Moncion [for the 1955 Radio-Canada broadcast]. It was done for them, but it was filmed with Jacques d’Amboise. Jacques was fine in it, but there was a mystery about it, there was a whole different connotation, when Frank did it. And they should never do La Valse again. Because nobody will ever dance it like she did. Mimi Paul had a career doing La Valse. I saw her do it, and she was beautiful in it. But I never wanted to see it again, after Le Clercq no longer danced it, because Tanny thought about everything. How she took the hand and put it in the glove. And the épaulement, and the way she used her head. It’s just so special. A real thinking performance.

She was incredibly bright, right? Her letters are wonderful.

Yes. Brilliant, brilliant. And very private.

So that’s why she never wrote an autobiography?

That’s right. Very private. She was the sort of person who could be so much your friend at one moment and then… Not that she was ever your enemy, but there were moments when she wanted to be by herself, quiet. She could be part of a group and funny. But at other times you knew she was to be left alone.

Photo: uncredited, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

The whole company must have been devastated when she contracted polio.

Yes. My wife and I had dinner with Mr. B and her the night before she got sick. That was on the 1956 European tour. We started in Salzburg, Austria. I had bought a black moiré scarf, a sort of a large scarf. Tanny wanted to use it as a stole. I was wearing it one night, and she saw it and she said, “Bobby, can I wear that scarf?” I said, “Sure.” I whipped it off and gave it to her, and she put it on because she was a little bit cold. It didn’t occur to me until much later that she had never given it back. So we went to Vienna and we went all through Switzerland. We went to Venice, went to Berlin and all through Germany and Belgium and danced in France. We were in Cologne, Germany, which was the third-to-our-last stop before coming home. Ginger and I had set a date to be married, so we were out looking at wedding rings in Cologne. And Mr. B and Tanny and Diana [Adams] were walking along. We got to looking into the window of a men’s store, and Tanny turned to me and confessed that she had lost my scarf and that she had been looking the whole tour to replace it. Mr. B I think maybe felt a little bit guilty so he asked Ginger and me to come back to the hotel with them and have dinner. Maybe 10 minutes after we got there, Tanny excused herself. She said she was not feeling well, and she got up and went to their room. We finished dinner and left.

The next day, we got on the train and headed for Copenhagen. She did Swan Lake on opening night. Second Act Swan Lake, a role she hated. And I’m not sure she was feeling good either. Next day she was due to do Caracole, which was a Mozart ballet that eventually became Divertimento No. 15. [But] she didn’t dance. Yvonne Mounsey learned the role and was going to dance. I was not on that night. I was having dinner at a restaurant near the stage door and waiting for Ginger, who was dancing in the third ballet. Mrs. Le Clercq [Tanaquil’s mother] arrived at the stage door and asked me if I had seen Mr. B. I said, “Yes, I saw him onstage. He was rehearsing Yvonne in Caracole.” She said, “Well, I need him.” In that theatre there was a scenic loft in the middle of the building that went all the way to backstage of the theatre. So there were two entrances to the stage, but you couldn’t get across. You had to either go this way or go this way [demonstrating]. So I said to her, “I will go this way and you go that way so we don’t miss him.” I went all the way to the stage and he wasn’t there, so obviously he went the other way. Mrs. Le Clercq took him back to the hotel. [The next day] they discovered she had polio. It was very fortunate that the doctor who was the house doctor for the hotel was moonlighting. He was a doctor actually at the polio clinic. He got her into an ambulance. At the polio clinic, she went immediately into an iron lung.

And then I never saw her again until she came back to New York, where she was at Lenox Hill Hospital.

Wasn’t she in Copenhagen almost a year?

I don’t think it was a full year but it was a long time. Jerry Robbins brought her home. He got her on a plane and brought her home. She was only here in the hospital for a short time, and then she went to Warm Springs, Georgia. Ginger and I were married on July 20 1957, and we went the next day after our wedding to see her. I used to see her all the time when I came to New York, but she… she never got out of the wheelchair.

I don’t know how a dancer survives that.

I heard yesterday that she was thinking about stopping dancing. That she really was wanting to write, and she was thinking about stopping dancing.

Maybe she was exhausted at that point. I’ve heard that the downside of becoming a Balanchine muse is that he demanded so much of you, and took everything out of you, in a way.

I have no idea what that was like [laughing].

On The Nutcracker

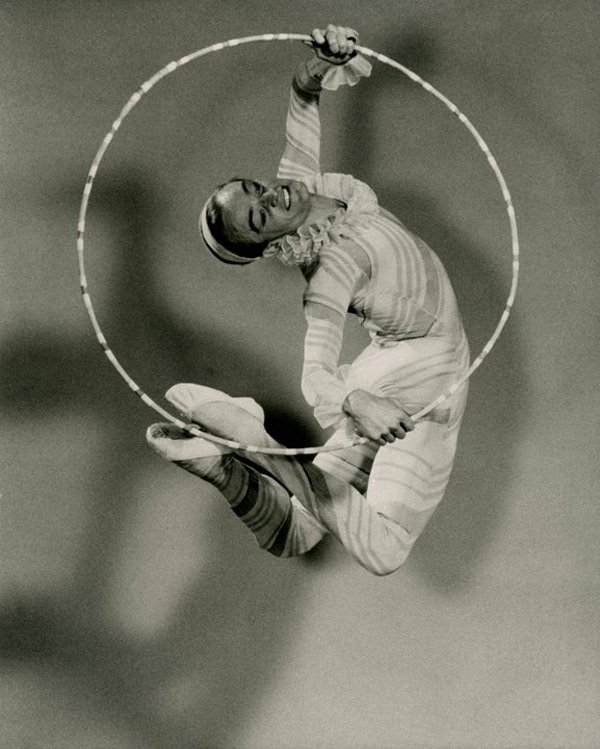

Did you know when Balanchine set Candy Cane on you that he had danced it in his youth?

Yes. He told me that.

Photo: Radford Bascome, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

Balanchine’s choosing you to do the one dance in his version of The Nutcracker that he had kept intact from the original 1892 production, and that he himself had danced, seems to me an enormous compliment.

I don’t really remember how he ever proposed it, but I remember it as being an absolutely pleasant experience. And the fact that he always rehearsed it. Other people rehearsed other things in the company but he always had his hands on that dance. He was the same way with Serenade. He always rehearsed Serenade. He had certain favorites which were a pleasure for him. But he told me while he was teaching it that it was the only piece in his Nutcracker that was from his days as a child. He had watched it before he went to the Choreographic School [the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg], and then he eventually danced it.

On Jerome Robbins

Your dates in the company almost exactly coincided with Robbins’ dates with the company, until he came back in 1969 with Dances at a Gathering. And Robbins cast you in every single one of his ballets, didn’t he?

Yes, and he used me as a guinea pig. I learned a lot of the parts. I learned both solos in The Cage. … If I didn’t have a rehearsal, he used to grab me and we’d go into a studio, and he’d start working things out. I did the premiere of The Concert, but the principal role was Todd Bolender’s. He [Robbins] had taught me one version – because Jerry was prone to change everything all the time …

Really?

Oh, God, you could learn 56 versions and he’d come in opening night and want you to go to version No. 25…. Anyhow, before the premiere of The Concert, I was getting ready to do my role. Todd was the Husband in it. But then that night, Todd was sick and was not going to do the premiere. So Jerry called me downstairs onstage fifteen minutes before the curtain went up and asked me if I remembered what he had taught me. I said, “I remember what you taught me, but you did something entirely different for Todd and I haven’t a clue what that is.” So we spent ten minutes meshing my role and Todd’s so there would always be somebody onstage and I went back up and put on my makeup and did both roles. But he changed it for everybody, and Yvonne [Mounsey] and Tanny were involved in it too.

Photo: Radford Bascome, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett.

How much Robbins did you do as director of Atlanta Ballet, if any?

None. For my 25th anniversary as director there, I asked him for Interplay. I was going to bring back Gil Boggs, one of my students, who was at American Ballet Theatre at that time, and I had students who were dancing in Europe. I wanted all the people who were away – very strong dancers – to do Interplay. So I wrote Jerry and asked him for Interplay and he wrote me back and said, “Send me a film of the company so I can see the dancers, and then I’ll let you know.” So I did. I sent it off right away, and I didn’t hear and didn’t hear. This performance was in the beginning of November. Well, I got a letter from him at the beginning of February saying, “Bobby, you can do Interplay. I’ll send someone to teach it.” I wrote him back and said, “Well, Jerry, you’re about three months too late.” [laughs] That was Jerry.

Robbins’s style is quite different from Balanchine’s, and it looks like it must feel different to dance because it’s often a more-relaxed style. Does it feel different to dance?

Yes. The thing is, Mr. B worked very fast because the music was terribly important and he went by the score. So he moved very fast, and he knew when he walked into the room what he was going to do. Also he expected you to respond. Like if there were four sections on the stage, he might teach this group here [gestures on the table]. You had to do it opposite to them. But Jerry took forever. You knew what your little fingernail was doing when Jerry choreographed. And he did umpteen million versions, and you never knew what you were going to do until the last day before you went onstage and a lot of times not even then. There was one time where it was absolutely devastating. We did a ballet that was very short-lived. Very expensive costumes [This was a 1954 work called Quartet, set to Prokofiev’s String Quarter No. 2, op. 92.] I remember he was never happy with it the whole time we were learning it. So he kept changing it. Every time we’d go into rehearsal he would change it. He would either create something new or he’d go back to a former version. Well, this was opening night and we were all onstage in costume, warming up, walking around, trying to get the choreography to gel. He walks on and says, “We’re going to do the 23rd version.” We all looked at each other and said, “The 23rd version? What version is that?” One of us knew it – it was either Jillana or Yvonne Mounsey or one of the other boys. But, anyhow, we all got our heads together and pulled it out of ourselves. And we went onstage and did it.

I had a terrible experience with him in London, the first time we went there in 1950. He had just choreographed Age of Anxiety to the Bernstein score and Auden poems. There was a place [a section of the ballet] called The Seven Stages. The ballet was made up of different sections, and each one of them seemed like a different ballet. Well, he decided he wanted to change the section I was in. I was sort of the central character in it. I got thrown in the air, and I got rolled offstage. He decided he wanted to change my exit and Frank Moncion’s entrance. So we were on that Covent Garden stage, which is a wooden stage, and he had me rolled off, he had me thrown, he had me jumping and grabbing ahold of Frank. He had me doing everything. And he got so frustrated that all of a sudden it was my fault that it wasn’t working. He stopped and berated me in front of the whole company because it wasn’t working. I was bruised and tired and I turned to him and I said, “Look Jerry. I’ve done everything I can possibly do to make this work for you, and if it doesn’t work that’s too damn bad, but I’m outta here.” And I left the stage and went down to the dressing room and I thought, “You’re going to be on a slow boat back to New York.” (It was my second season in the company.) And then I thought to myself, “Just calm down. You either have a job or you don’t.” So I took off my clothes and put on a robe. The showers were in a sub-sub-basement, so I went down and took a shower. I took my time and then finally went upstairs to get dressed, and Jerry was sitting at my dressing room table. He said, “Bobby, we’re going to leave it like it was.” But I never had a problem with him ever again.

Photo: uncredited, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

Every dancer has stories about working with Robbins.

Oh yes. I loved working for him. I loved doing his ballets. But I wasn’t going to take abuse – from him or anybody else. And that’s what it was. It was just plain abuse. He would do it as long as he could get away with it.

On Frederick Ashton’s Picnic at Tintagel and Bronislava Nijinska

Can you remember all the principal or featured roles that other choreographers made for you while you were at New York City Ballet?

Well, let’s see. … I did two ballets by Frederick Ashton: I did the Dandy in Illuminations [1950], and I did Merlin in Picnic at Tintagel [1952]. I did the Truck Driver in Lew Christensen’s ballet Filling Station. What else? I don’t remember….

I love your story about what happened when you auditioned with Frederick Ashton for Picnic at Tintagel. Can you tell that story?

In the ballets that Ashton did for our company, where you were a certain character, he used to audition people individually. He would take you into a room and he would give you a verbal explanation of the role you were going to do. Then he would want to see your reaction and how you would interpret that role or that particular character. We were in the process of doing that, and he stopped me about five minutes after we were there and he said, “You’re not a product of the School of American Ballet are you?” I said, “No.” And he said, “I know exactly who you studied with: Bronislava Nijinska.” I said, “How can you possibly know that?” He said, “Because she was my teacher as well, and for me, she’s a university of the dance. There’s no one like her.” He was in the Ida Rubinstein company when Nijinska was there. He used to say that when Nijinska was choreographing, if he was not being used, he would sit in a corner and watch her. Just watch her. The way she used the music and the way she choreographed and how she approached everything. He said he learned his craft from her. And Ashton [many years later, when he was director of the Royal Ballet] brought her back to the Royal Ballet to stage Les Biches and Les Noces.

Photo: uncredited, from the collection of Robert and Virginia Barnett. (Click image for larger version)

On Directing the Atlanta Ballet

You and your wife were invited by Atlanta Ballet founder Dorothy Alexander to join her company as principal dancers and co-associate directors in 1958, and you took over sole direction of the company in 1962 when Alexander retired. During your tenure, the company gained professional status. Can you talk about that?

When I went to Atlanta, the budget for Atlanta Ballet was $16,000. It was a very, very strong nonprofessional company. Dorothy was an excellent teacher, but she just didn’t have the funding [to pay dancers]. Her whole purpose was to train dancers and try to keep them in Atlanta by creating a professional dance entity instead of a nonprofessional one because at that time, you were training dancers and they were all running off to New York. We eventually were able to take the company professional, in 1967, and so keep the dancers home. When I left, the budget was still not that much, but it was $4,600,000.

You mentioned during the Video Archives filming that in 1959 Balanchine gave you the rights to his Nutcracker. I read on the Atlanta Ballet’s website today that he gave you the rights to Serenade at the same time. How did that happen? Did you ask him?

I asked him for it, yes.

Both of them?

Yes. I have a letter that he wrote to me and my wife when we left the company, saying that we were allowed to set any of his ballets that we could remember. I still have that letter.

Balanchine knew that I was going to take care of his ballets. He knew how I was offended every time I saw somebody change the choreography. I was that way with my dancers, too. I sometimes had problems with my dancers wanting to do roles that they really weren’t suited to. I would just say, “No. I’m not thinking about you. I’m thinking about the ballet, and that’s important to me. And I don’t want you to look bad in that ballet. So you’re not going to do this role.” A lot of them refused to dance. I said, “Fine. There’s somebody standing right behind you who will do it better and doesn’t have an attitude.”

I was offended when I saw the Royal Ballet do Serenade and change the choreography. The Waltz wasn’t a semblance of what it was supposed to be. I was in London and saw that and came back through New York and went up to see Betty Cage, who I was very close to….

When was this?

This was probably in 1965. I said to Balanchine, “Mr. B, do you know who’s taking care of Serenade in the Royal Ballet? He said, “No, it’s been several different people.” I said to him, “Well, you wouldn’t recognize your ballet. It’s just terrible what they’ve done to it.” He said to me at the time, “You know, Bobby, when I’m gone, they’ll all be changed.” And I said, “Well, not as long as I’m still here, they won’t be changed.” But he was so right. They have been changed. A lot of them have been changed. And it’s such a shame. The fact that [the Balanchine Foundation] is doing this [filming original interpreters coaching the roles Balanchine made for them] is great.

© Lynn Donovan. (Click image for larger version)

When did Atlanta Ballet first perform Serenade?

In 1960. It was set by Una Kai, she was working for Mr. Balanchine, staging his ballets, at that time. I staged it from then on, with Ginger’s help. Ginger had danced it in the NYCB. She was in the Canadian television broadcast of it [in 1957]. She’s one of the front girls and she does the Russian Dance. Serenade was her very favorite ballet.

© and courtesy of Greensboro Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

You later staged Serenade for Philippine Ballet Theatre for their 1989–1990 season.

I set a whole Balanchine evening on them. I set Who Cares?, Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux, Concerto Barocco and Serenade. I did the same thing in Taiwan [in 1990]. That was also an all-Balanchine program. Again, we opened with Serenade, and we did Prodigal Son and Four Temperaments. I went to Taiwan and did an audition of dancers from all pre-professional studios in Taipei invited by the Minister of Culture. I chose 17 girls for the corps de ballet in Serenade, boys for the corps de ballet in Prodigal Son, and then we did The Four Temperaments with no guest dancers involved. All principal roles were danced by the Atlanta Ballet dancers. The dancers in Taiwan had never had the experience before. It was a very popular program. We were there for five days, and did the same program every night to full houses.

Balanchine’s production of The Nutcracker is wonderful, and, as you mentioned earlier, The Nutcracker is a moneymaker for ballet companies, subsidizing the rest of the season. Is that why you asked Balanchine for the rights to stage his version? Or because of your attachment to it? Or both?

Well, both. I thought it was an incredible ballet and I was new to the company there, and we wanted something for the holidays. So I thought, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.” So I asked him if we could possibly do his Nutcracker. And he said, “Sure.” And he never charged me a royalty.

In the beginning [in 1959], I staged the whole second act and I did Snow. And then in 1965 we did the whole ballet for the first time. Victoria Simon came and taught it. I did it as a gift to the city. I got the [Atlanta] Journal-Constitution to pay for it. They paid for the theatre, they paid for the costumes, they paid for the sets – they paid for the whole production. People wrote in to the paper and asked for tickets, and the newspaper gave them out. Then, after that first year, it was ours to sell.

That’s such a nice idea. Whose idea was that?

Mine [laughs]. We did it for several nights to sold-out houses.

© Charlie McCullers, courtesy of Atlanta Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

What was your approach to choosing repertoire?

I felt that for my audience in my city, which is rather a traditional city, they wanted to see traditional dances, and I wanted to educate them. Not only to give them what they wanted, but to expand and educate them. For the traditional side, I brought in David Blair and his wife from the Royal Ballet to stage Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and Giselle. We did them in three different years, starting with Swan Lake [in 1965].

And then to educate my audience I brought in people like Lynne Taylor-Corbett and Todd Bolender. I did a whole season with a choreographic group that came out of Pennsylvania run by Barbara Weisberger. And I brought in guest companies: Baryshnikov with Mark Morris, Twyla Tharp, Dance Theatre of Harlem.

How many Balanchine ballets did Atlanta Ballet perform under your directorship?

We had about 15 of his ballets. I picked mostly what I felt were classics. Serenade was the first one, and we did Concerto Barocco. We did Allegro Brillante, Scotch Symphony, Four Temperaments, Prodigal Son. And we did Theme and Variations, Square Dance and Tarantella. And Raymonda Variations we did.

At one point, I asked Balanchine for Pas de Dix. He said it was Petipa’s choreography, not his: “It’s not mine; you can do it.” So we did Pas de Dix as well.

Absolutely splendid interview of an absolutely splendid individual, whom I have been privileged to call my friend. And with thei nformation, Bravo ten times over.

Wonderful interview! Thank you. I had heard the name Robert Barnett and seen photos, but knew little about him.