© Courtesy of Geimaruza. (Click image for larger version)

Geimaruza

Nihon Buyo Dance

★★★★★

New York, Japan Society

3 March 2017

www.geimaruza.com

www.japansociety.org

Nihon Buyo at the Japan Society

That the Japan Society should host a sophisticated evening of superlative dance comes as no surprise; the cultural center regularly offers performances by extraordinary Japanese artists. I remember a revelatory evening of Okinawan dance in 2015 (more please!). This weekend, it hosts Geimaruza, an ensemble of young artists, all graduates of the Tokyo University of Arts, performing nihon buyo, or Japanese dances associated with the kabuki tradition. It would be a shame to miss them.

© Julie Lemberger. (Click image for larger version)

The dances are a mix of traditional, from the 18th and 19th centuries, and more modern reinterpretations, like the danced folk-tale Oshukubai (The Nightingale in the Plum Tree), which dates from 1948. All are performed using pure kabuki technique and costuming; there is nothing jarringly updated or anachronistic here. As the program note explains, however, the very idea of performing these dances as stand-alone pieces, separate from the dance-dramas in which they originally appeared, is a late twentieth-century one. Freed from their dramatic context, the dances are revealed as pure-dance miniatures.

The varied program included three dance works and one musical interlude. Each section was excellent, and revealed a different aspect of the dance and music that constitutes this repertoire. The musical ensemble of chanters, shamisen (a banjo-like instrument), percussion, and bamboo flute, played throughout, at first on a tiered platform at the rear, later seated on the floor on opposite sides of the stage. I loved how their expressions remained completely neutral, eyes downcast, even as they produced exciting whoops and growls. Only once did I happen to notice one of the percussionists following the action with his eyes.

© Julie Lemberger. (Click image for larger version)

Various forms of expression, from the broadly comic to the highly poetic, were explored. Ayatsuri Sanbaso (Puppet Sanbaso) was a whimsical piece for a small dancer (Hanayagi Ohhisui) depicting a puppet manipulated by its puppet-master (Hanayagi Tatsuma) with invisible strings. A western viewer is immediately reminded of Coppélia or of the various toy characters that populate ballet. With her face painted like a porcelain doll, Ohhisui moved with jerky, broken movements, growing increasingly wilder until she fell, seemingly broken. My favorite moment came when the puppeteer “fixed” one of her imaginary strings; delicately, he took the invisible filament in his fingers, knotted it, and pulled at the knot with his teeth.

In the story of the Nightingale in the Plum Tree, sound effects were as important as the dance and mime. The story hinges on the contrasting sounds of the nightingale’s song and the ugly call of the crow, the crow’s caw caw and the nightingales’ beautiful ho-o ho-o kekyo. The vocalizations ricocheted from one character to the next, echoed by one of the singers in the musical ensemble. The short, comic piece is drawn from a folk tale about a crow who tries to impersonate a nightingale in order to convince a plum tree to allow him to rest on her branches. Each character has his own movement style and voice; delicate and slightly ditzy for the tree (Fujikage Shizuhisa), broad and grotesque for the crow (Hanayagi Genkurou), noble and sinuous for the nightingale (Fujima Toyohiko). Interestingly, the dancer playing the tree does not try to resemble a tree, but rather remains a delicate maiden. When the nightingale arrives, he doesn’t attempt to “land” on one of her branches, but mimes opening a sliding door and stepping over the thresh-hold. Animal and human behavior collide.

© Courtesy of Geimaruza. (Click image for larger version)

After the break, the musicians took over. First, a tour de force for two shamisen players (Touon Minamidani Mai and Touon Sakata Maiko), playing in unison, call and response, and harmony. Then, a haunting solo for the flutist, Tosha Suiho. And finally piece for percussion, flute, and voice, ending with a great accelerating flourish.

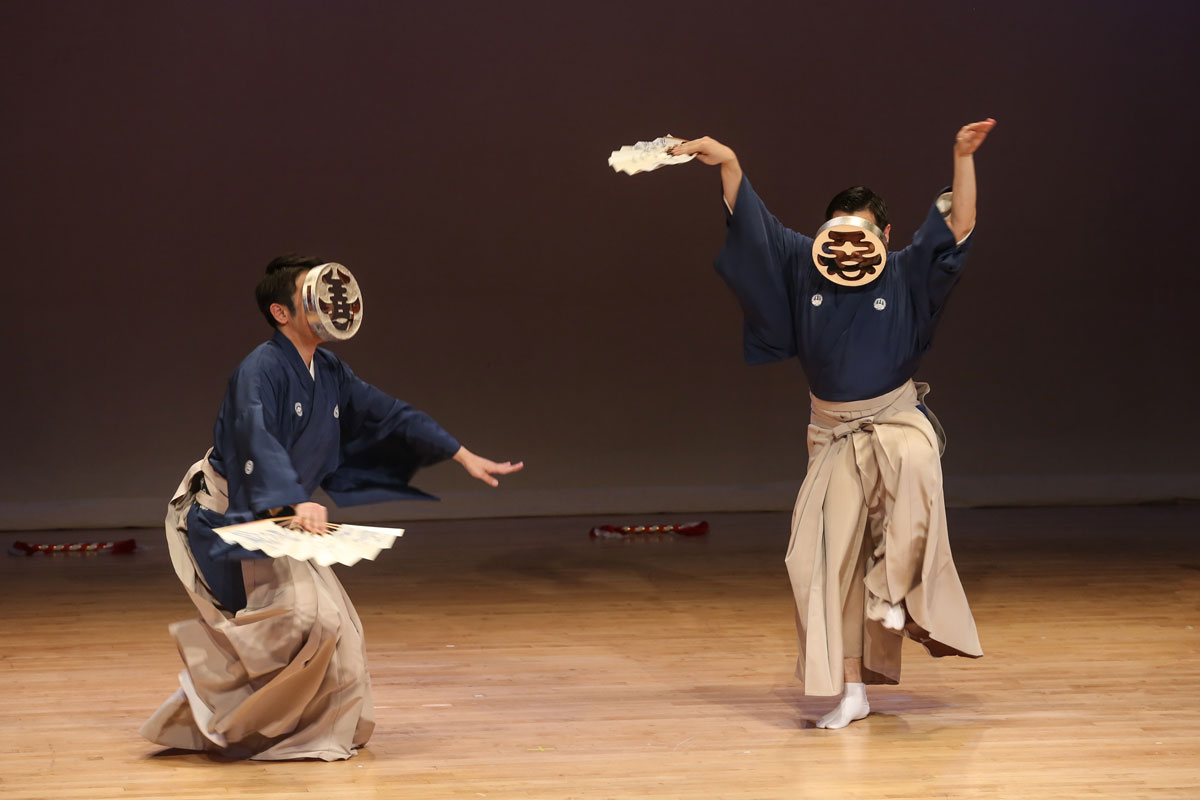

This, in turn, led into the evening’s most extraordinary work, a suite of dances depicting the four seasons (Shunkashuto). Here, the costuming was sober: monochrome kimonos in pale colors and silver fans, clean faces. Each season received a different treatment. Spring was a young woman (Shizuhisa), whose gliding movements gave way to a simple but mesmerizing ribbon dance. (Which made me wonder whether the modern dancer Loie Fuller had seen any Japanese dance?) For the segment depicting summer two men entered and put on metallic, abstract masks, which they held with their teeth. Then they engaged in a kind of acrobatic superhero battle. Two women represented fall, first with a spinning umbrella dance and later with cartoonish masks that turned them into canoodling lovers. And finally, just as the suite was beginning to feel a tad gimmicky, it concluded with an exquisite fan dance in which the fans, manipulated into breathtaking figures, became the falling leaves, snowflakes, and the wings of birds skimming across the water on their voyage south. An image of pure poetry.

© Julie Lemberger. (Click image for larger version)

What was remarkable about these pieces was how legible they were; there was no barrier to comprehension. The jokes were funny and the stylistic differences between characters absolutely clear, even for an untrained eye. That is one of the advantages kabuki has over noh; because it was conceived as a popular entertainment, it is by its very nature accessible. And, even without being a connoisseur of Japanese dance, one senses the modernity of Geimaruza’s presentation. The dances look absolutely fresh and of our time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.