© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Whipped Cream

★★★★✰

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

22, 24 (mat) May 2017

www.abt.org

The Confectioner’s Art

Alexei Ratmansky’s new ballet for ABT, Whipped Cream, is like a Viennese confection: so layered and airy that it takes a moment to fully take in the flavor of its many ingredients. That’s not unusual for a Ratmansky ballet. The second helping is usually better than the first.

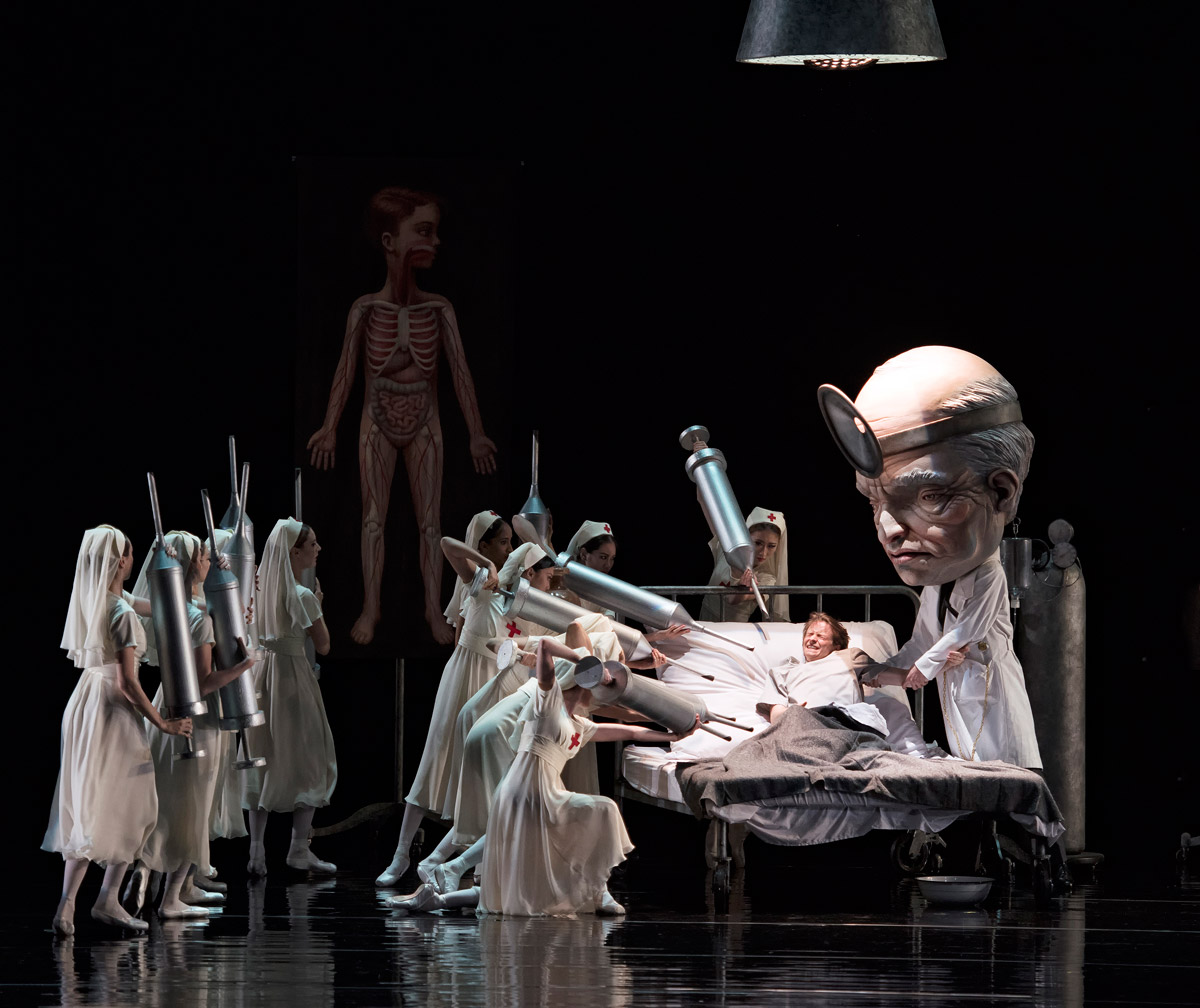

For those who haven’t heard of it, Whipped Cream, or Schlagobers as it was originally called, is a ballet with a confectionary theme by Richard Strauss which had its premiere in Vienna in 1924. The choreographer was Heinrich Kröller, a German then on the staff at the Vienna State Opera. Its trifling story deals with a boy who, on his confirmation day, overindulges in whipped cream in a pastry shop – a place likely inspired by Demel’s in Vienna – and ends up at the hospital with indigestion. Once he’s been carried off, the denizens of the pastry shop – marzipan men, Princess Tea Flower, Prince Coffee, et al – pop out of their tins and have a party. In act 2, the boy is harassed by a doctor and his stern nurses, intent on poking him with their hypodermic needles. A twinkly princess, sovereign of the Pralines, comes to his rescue, as do a trio of liqueurs, who manage to inebriate the hospital staff and whisk him off. All ends to the boy’s delight as he escapes to a candy kingdom where he can eat as much whipped cream as he likes.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The ballet was a rotund flop in 1924 and was never heard of again until Ratmansky decided to give it another go for American Ballet Theatre. (Actually, he used a little bit of the score years ago for a miniature he made for himself and his wife, who, upon arriving in Canada from Ukraine in the nineties, was delighted to discover American whipped cream in a can.)* The curious thing is that at the ballet’s premiere in Vienna, critics scoffed at the score, which turns out, for the most part, to be quite good, full of soupy waltzes and child-like laëndlers, with a big, celebratory tarantella a the end. But then, critics were always giving Strauss a hard time for being too lowbrow, too sentimental. “People always expect big ideas from me, big things,” the composer of Rosenkavalier once lamented, “haven’t I the right after all to write what music I please?”

There’s quite a bit of Rosenkavalier in the score for Whipped Cream, as well as Ariadne auf Naxos and references to Mozart and to other composers. (Is it possible that I heard an echo of Ali’s variation from the ballet Le Corsaire?) In any case, it’s opulent, tongue-in-cheek, at times faintly exotic, and at others – as in the long pas de deux in Act I – as ardent as anything he ever wrote. Not all of it, like the sinuous violin melody that accompanies the pas de deux, gorgeously played by Benjamin Bowman, is easy to set steps to, but Ratmansky has pulled it off. As with the music of Shostakovich, he has managed to match its spirit, in this case with a style that is rococo and playfully over-the-top, as decorative and droopy as an art-nouveau interior. The tone is ironic, but without the mordant edge that irony often implies.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

In short, it’s a light, frothy, and yet sophisticated piece. Its absolute resistance to deeper interpretation won’t please everyone, but at today’s matinee, there was a constant bubbling up of laughter, a welcome sound in times like these. The ballet is enormous, well-crafted fun. There’s quite a bit of slapstick humor; one of the highlights is a number for a trio of dopey liquor bottles. It may be silly, but the solo for Mademoiselle Marianne Chartreuse is a little jewel: she stumbles on, twists her cork, shakes herself, and then launches into pretty, sharply-accented piqué arabesques, taps the floor with her pointe, or does a gargouillade on a trill. On opening night, Catherine Hurlin, who joined as an apprentice in 2013, stole the scene completely.

The ballet is full of moments like these: the solo for Princess Praline begins with a little self-introduction in which the princess points at her crown a reference to the usual balletic mime for “I am royalty,” but as she does this, she wiggles her hips; the juxtaposition of formality and teenaged flirtyness is adorable. The boy imitates her, delightedly, while biting his nails. At the end of their duet, she steals a kiss. The grand pas de deux for Princess Tea Flower and Prince Coffee in the first act is like something out of a Rudolph Valentino movie. She’s an incorrigible flirt, with droopy art nouveau arms and a tendency to vamp; he’s an equally vampy lothario who throws himself at her feet and crawls across the stage like a panther. The ballet’s finale, with the whole cast clapping in time to the big waltz (introduced earlier in a more delicate version) while the boy explodes into split jumps and double assemblés, is generous and happy. Even better is when the crowd tosses the boy into the air not one but four times, higher and higher until you begin to worry. Some will recognize the toss from Ratmansky’s recent ballet Odessa for New York City Ballet. There, it had darker, more ominous undertones, as if the character were being buffeted by forces beyond her control. There is a quotation from another recent ballet, Fairy’s Kiss, as well, a haunting lift in which the dancer’s body, supported by three men, arches up and away, almost as if it were flying.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Not everything works perfectly, particularly in the first act. Both Tea Flower’s solo and her pas de deux with Prince Coffee are a bit too long; by the end, there are not quite enough movement ideas to fill the music. Prince Cocoa and Don Zucchero’s solos, though both funny and intricate, feel superfluous. The first scene, in which the children indulge at the pastry shop, is too short, so you barely have time to understand what’s happening before candies start popping out of tins. (The boy then disappears until Act II.) There aren’t enough dancers in the whipped cream waltz at the end of Act I, and the waltz itself is a little disappointing. It’s the one spot where the choreography doesn’t capture the sweep of the music.

Most of these issues fall in the first act, but I found that already on second viewing, they seemed to matter less. Perhaps the ballet was beginning to settle. The orchestra, under David Lamarche, sounded stronger and more rehearsed, and the dancing was clearer. The second cast, led by Jeffrey Cirio (boy), Skylar Brandt (Praline), Devon Teuscher (Tea Flower, replacing an injured Gillian Murphy), and James Whiteside (Coffee), really conveyed the spirit of the ballet. Teuscher and Whiteside, in particular, made much of the stylish, vampy pas de deux.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

There has been much talk about the designs, by the pop surrealist painter Mark Ryden, and rightly so. They are an equal partner in the ballet, a source of visual excitement and caprice. The scene in which Praline enters on a giant, wide-eyed “Snow Yak,” conveyed by two dancers (like the Lilac Fairy on her boat) and followed by a furry giraffe, a snake creature (who slithers around on a skateboard), and a woman who looks like a pile of gumballs, is so improbable that it makes one want to laugh out loud. The doctor and pastry chef wear giant heads, for which Ratmansky has choreographed simple, but effective movements. In the hospital scene, an eye stares out into the darkness; every now and then, it blinks ominously. The whipped-cream landscape is sumptuous, though it’s too bad that it obscures the slide that conveys the dancers onstage. The final city-scape is layered and colorful and inviting – a giant bee hovers above it all, and Abraham Lincoln stares down from a third-story window. It’s weird and silly and beautiful all at once.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The company seems to have taken to the ballet like a boy to whipped cream. In addition to the people mentioned above, I was struck by Thomas Forster, as a dashing Prince Cocoa, dressed as a musketeer, completing a tricky combination of jumps and turns; and Blaine Hoven as Don Zucchero, turning like a top while holding his foot as if he’d stepped on a nail. On opening night, Daniil Simkin was a more petulant version of the boy, but his jumps had all the zing you could want. Stella Abrera and David Hallberg took a more elegant approach to the big pas de deux in Act I, a valid choice, if a less funny one. (But boy was it good to see David Hallberg onstage again!) Sarah Lane was a pert, quick-footed Princess Praline. Like Don Quixote or Sleeping Beauty, this is a ballet that shows off the whole company.

So, if you loathe confectionary, run like the wind. But remember that sometimes, cake makes a nice meal, all by itself.

* I should mention, I’m writing a book about Alexei Ratmansky, which is why I know this story.

I saw the same two performances. I completely agree with you on the second cast being clearer. To me Devon Teuscher was a revelation. She had precision, charisma and a witty wink and a nod that didn’t tip over to exaggerated silliness. It was her dancing that (finally) revealed the choreography’s intention and charm through the busy steps and upper body frilliness and how they correspond to the (unfamiliar) music.

So glad to hear we saw the same things! 🙂