© Courtesy New York Baroque Dance Company. (Click image for larger version)

www.nybaroquedance.org

www.calperformances.org

Meticulous reconstructions of Petipa, Cunningham, Graham, Taylor works are performance staples these days. Much rarer is a reconstruction like Le Temple de la Gloire (The Temple of Glory), a 1745 political opera-ballet with music by Jean-Philippe Rameau and a libretto by the philosopher Voltaire. It could be described as a unicorn of the ballet world: Performed for France’s King Louis XV in 1745 at the Palace of Versailles, it was revised and remounted in Paris in 1746, then never seen again. The work displeased His Majesty, who did not appreciate Voltaire’s allegorical tutelage on the virtues of benevolence over bloodlust.

At long last, Le Temple de la Gloire has returned to the stage, and it has much to tell us about ballet then and now. Catherine Turocy, the artistic director of the New York Baroque Dance Company and one of the world’s foremost experts on Baroque performing arts, created thirty dances for the production – dance comprises fully half of the stage time, a mixed-media format that was standard in the 18th century. No records of the original choreography in existing Feuillet notations, the dance-recording method of Rameau’s time, so Turocy based the dances on her knowledge of the era and on existing notations of ballets on similar themes: heroes and muses, gods and demons, bacchantes and satyrs, shepherds and kings.

Nicholas McGegan, artistic director of San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale, led the drive to restore the magnificent three-hour spectacle; he also conducted the 43-piece orchestra, seven soloists and 24-person choir. McGegan and Turocy worked alongside scholars at U.C. Berkeley, where the original manuscript and score have been housed since 1962, and the production was co-sponsored by the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles and Cal Performances, who presented the world premiere at Zellerbach Hall April 28–30.

© Frank Wing. (Click image for larger version)

The morning after the opening, Turocy sat down to discuss the dances in Le Temple de la Gloire and reflect on what Baroque dance reveals about ballet, both what the art has gained since the 18th century and what it has arguably lost. Jennifer Meller, one of Turocy’s rehearsal dancers and the dance director of San Francisco Renaissance Voices, joined in. This is an edited version of our conversation.

CB: Describe the concept of the 18th-century opera-ballet. Today we think of ballet and opera as essentially separate, but for a long time the worked together.

CT: Basically, the dance is seen as a dramatic vehicle that will tell things that the public can’t hear, in the sense that they cannot be said. But through actions, you can say quite a bit. So it’s an equal responsibility to tell the story. In this work in particular, there are thirty arias and thirty dances, plus the choral music and the instrumental music. The dance portion of it is almost 50 percent.

CB: There is such a strong connection between Baroque dancing and the ballet of today. As I was watching Le Temple de la Gloire, I could see a through line from there to Ratmansky’s 2016 reconstruction of Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty, with that late-19th-century technique, and then, say, to Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée and finally contemporary ballet. You see how the technique has changed, and the origins of it. In Ratmansky/Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty, you have the low arms, you have the low extensions, you have all that beautiful footwork you see in Baroque dance.

CT: Exactly. I saw [Ratmansky’s] Sleeping Beauty; I thought it was unbelievable. [The 18th century] is the time period where the positions of the feet were established, the idea of plié, relevé. That was probably a big break from what was going on in the Renaissance, and a break from traditional dance, that idea of being up on the ball of your foot – and of course, later, on the toe – as opposed to being down and playing the ground like a rhythmic instrument. In the Baroque style, you see the pas de bourrée, pas de chat, pas de basque, pas de cheval, pirouettes, entrechat quatre. But the [musical] measures are very dense. You could say that Baroque is like petit allegro in ballet, except with a different sense of rhythm and a different sense of energy.

© David Tayler. (Click image for larger version)

CB: How is the sense of rhythm different?

CT: For instance, Romantic music has longer phrases where there is a sustained note over four measures, and you might just do a long arabesque that then promenades around.

CB: Like in Giselle.

CT: Exactly. One of the ballet phrases I always love to do is temps levé, chassé, pas de bourrée, glissade, assemblé. If you were doing that a little bit more in the 1745 style, you might have a rond de jambe stuck in there, you might have a little bit of a petit battement. You might have two jumps, or a change of weight or a change of feet, like a chassé just before the assemblé, and then the assemblé would be like an assemblé sissonne. So it’s denser in the sense that every beat is considered, and when you’re doing a compound meter, the half-measure is also considered. I have found dance notations where it’s a compound meter, meaning it’s 1-2-3-4-5-6, but it’s 1-4, 1-4, and instead of having the bar lines every six beats, it might have the bar lines every three beats. But then you also find the opposite, like in a minuet, where the music is three beats, but then the dance is six beats. [In Baroque], there’s more play than you would imagine in fitting the dance structure to the music.

CB: People sometimes think of Baroque as stuffy, but it’s very playful and energetic and lively and expressive.

CT: It depends on what dancers you see doing it. If you have dancers who are only reading the signs of the notations, and feeling that they don’t have the liberty to add emotion or shapes, it’s mechanical. It would be like reading Shakespeare and just saying [speaks in monotone], “To. Be. Or. Not. To. Be.” This is a word, that’s a word. What do they mean? What’s the phrase? What’s the context? All of those questions need to be asked, even in just reconstructing a minuet from notation.

© Mark Gillespie. (Click image for larger version)

CB: In the shepherd dance in Act I, there were some serpentine shapes where you had seven or eight dancers winding in and out and through each other’s arms. I immediately thought of Balanchine.

CT: Oh! [laughs] It’s a very old, ancient idea, holding hands and going into a serpentine. One sees images of this in ancient Greek and Roman vases and paintings. And also in the Renaissance, there are a lot of dance of the period that are like that, circle dances. It’s both folk and stage. It’s been with us forever. And it’s in children’s games, like Crack the Whip.

CB: And of course Balanchine had so much folk dance in his quiver.

CT: Also, he was familiar with some of the notations from the 18th century. Because Diaghilev used to carry a book around with published dance notations, and he would say to his young dancers who wanted to be choreographers, “Study this. This is the basis of the beauty of the geometry.”

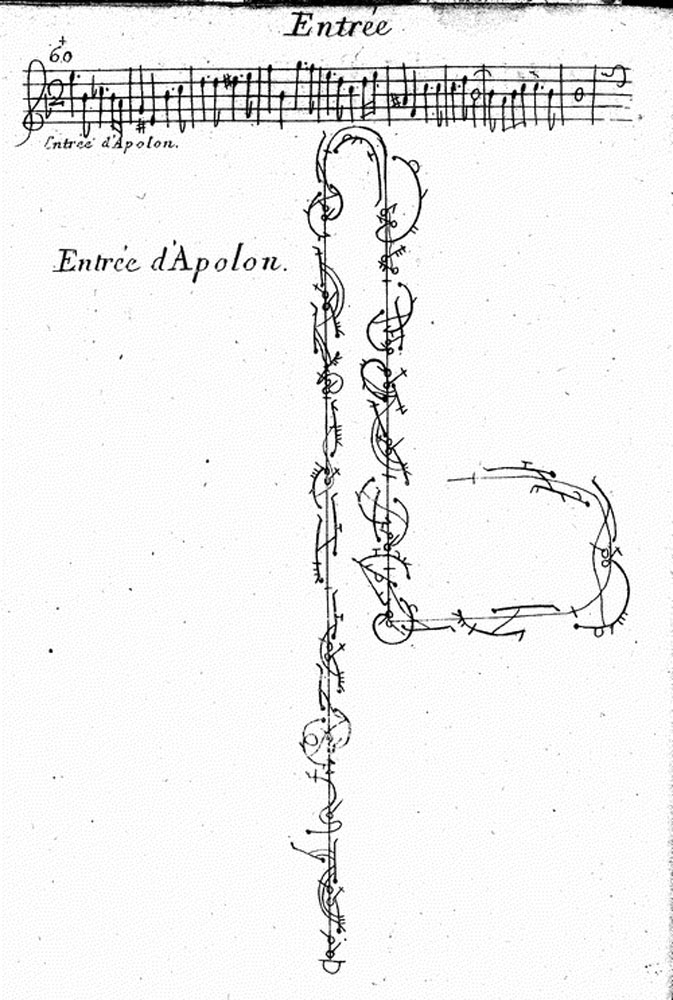

Courtesy earlydance.org. (Click image for larger version)

CB: Diaghilev had Feuillet notations?

CT: Yeah.

CB: And he could read them?

CT: That I don’t know! [laughter]. He could read the tracings – the tracings are really beautiful. That’s the map.

JM: When you’re teaching dancers Baroque dance for the first time, what are the top things that you start with? What do you need to let go of from ballet, or add?

CT: The first thing I want is to introduce the dancer to the concept of an original instrument, and that’s their body. So I start talking about Da Vinci and the Vitruvian Man, and the relationship of the microcosm and the macrocosm, how you think about different parts of your body being related to nature. Then that idea that there is a defined space, which is your universe, that you’re moving in, and you invite people to come into that or out of that. And how to use that sort of “energized bubble” that you’re in. They don’t talk about it in general training for ballet dancers. I think the very big difference is that instead of trying to make a very large grand jeté that is going to traverse the stage – which you could do in that time period, but it would be a grotesque movement, because it’s outside the normal movement range – what I try to do is get them to understand their own body proportions and their own normal movement range, and then to feel that that energy and intention is coming from the center of the body. When they see it in action, they realize that it actually does work on a large stage.

© Frank Wing. (Click image for larger version)

CB: Nowadays we complain that the emphasis is on dancing big, big tricks, virtuosity. But Camargo danced in Le Temple de la Gloire, and it was already about tricks – her technique was already sensational.

CT: There were a lot of people [at the time] doing entrechat huit. There were also these crazy [entrechats] where you would go between the French and the Italian way of jumping. The French way would be to have your legs turned out, and the Italian is to be almost parallel. So you jump in the air going “parallel–we’re Italian–switch–now we’re French–switch–now we’re Italian.” And they had something called the indeterminate pirouette, and that means you just go around as many times as you can. This information comes from a 1779 publication from Gennaro Magri [Trattato teorico-prattico di ballo, considered a crucial link between Baroque dance and early Romantic ballet technique]. The ancient Romans probably were doing crazy things! I think the hardest thing is for them to do something without effort, as opposed to always pushing.

CB: By “them,” you mean today’s ballet dancers.

CT: Ballet and modern dancers today. If you dance on pointe shoes, you either plié or you’re on pointe. To be just flat, in that middle level, in your pointe shoes, is not pretty. Most of the Baroque dance happens in that middle level. And just using the flat is an expression – it’s a low level, medium level and high level. So the whole training of the foot is different. And because the leg extensions [in Baroque] are not up here [puts her hand up to her ear], a lot of it is below the knee, you have to shift to a more central balance of the body. A lot of Baroque dance builds up those inner muscles that give you a stronger core of balance.

CB: Roughly 100 years after Le Temple de la Gloire you have Giselle, and you have the separation of dance and opera becoming complete. Why did they separate, after being together for so long?

CT: I think it was the French Revolution. At some point in Paris, you couldn’t say the words in an opera, because they were controversial or because they could be changed. For instance, there were a lot of political satires that used the words of opera, because everybody knew the songs, but they shifted something.

© Frank Wing. (Click image for larger version)

CB: To change it to an acceptable revolutionary message?

CT: Right. It was something dirty about the queen, or something dirty about the king, or something really bad about politics. After a while, they didn’t want to have operas – there was a time when they didn’t have words spoken at the Paris Opera, and they would just do the dance. And then you see that the ballet dancers are thinking, “Wow, I can do a ballet of The Marriage of Figaro, of Beaumarchais’ play. We’ll use the music, we’ll do all the pantomime so everybody knows what the story is, but we’re not going to use any of the words.” That way, it’s not gonna be cancelled. Dance took over when words became dangerous.

CB: Thank you, Catherine. And congratulations.

CT: Thank you.

Catherine Turocy’s annual historical-dance workshop takes place in Seattle, Washington, Thurs.–Sun., 29 June 29–2 July. This year’s theme is Nijinsky, with courses on his technique and works, as well as classes and discussions on Baroque dance, African dance, early ballet and social dances of the 19th and 20th centuries. All experience levels are welcome.

Claudia has accomplished another of her excellent jobs. Terrific.

Until her death, Angene Feves, who lived in the East Bay county of Contra

Costa, was an expert in the Italian ramifications of Baroque dancing and

wrote about Italian noblewomen who supported dance masters. She

would have applauded Claudia and Turocy.