© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

The Dream, Symphonic Variations, Marguerite and Armand

★★★★✰

In Marguerite and Armand the 3 casts reviewed are Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle, Alessandra Ferri and Federico Bonelli, Natalia Osipova and Valdimir Shklyarov.

London, Royal Opera House

2, 3, 5 June 2017

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

The Royal Ballet’s season is ending on a high, paying homage to its founder choreographer, Frederick Ashton, by fielding the company’s dancers and invited guests who can do him justice. Casting for the Ashton triple bill has provided challenging debuts for youngsters and remarkable performances from mature dancers, including a farewell role for Zenaida Yanowsky.

As the tragic courtesan in Marguerite and Armand she is both majestic and vulnerable. She knows that her love affair with a younger man (Roberto Bolle as Armand) can have no future but she can’t resist her last chance of bliss. Yanowsky conveys conflicting emotions through the subtlest of means: the carriage of her head, the fall of a hand, the stutter of her pointes. She’s dignified in her renunciation of Armand at the command of his father (Christopher Saunders), so her public humiliation is all the more painful. Bolle is almost too sympathetic and too mature as the callow youth, coping manfully with the sheer volume of his lover in her magnificent full-skirted dresses.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

When she dies of consumption in his arms his back is arched under the burden of raising her off the floor. He’s not a nuanced actor, so his anguish at the end seems histrionic. The genuine emotions evident in their curtain calls on the first night, as well as her last, was far more affecting. Though Ashton’s showcase for Fonteyn and Nureyev has served as a swansong for Yanowsky after her 23 years with the company, it’s not the ideal vehicle for her.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

It is for Alessandra Ferri, back again as a guest with the company she left in 1985. Coming out of retirement in 2013, she danced the role of an older woman renouncing her young lover in Martha Clarke’s Chéri, so she brings a hinterland of experience to Ashton’s Marguerite. Huge dark eyes burning in her expressive face, she has the feverish appearance of a stricken TB sufferer. Her tiny frame, though, is far from frail, and nor are those exquisitely arched feet.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Her first encounter with Armand (Federico Bonelli) leaves her thunderstruck: canny courtesans aren’t meant to fall in love. Bonelli, like Bolle, looks far younger than his years. He now has a magnetic presence on stage – and unlike the guest Armands, he knows exactly how to phrase Ashton’s choreography. He gives a different emphasis to all his arabesques (and there are a lot of them, originally intended to show off Rudolf Nureyev’s feline physique). Bonelli’s timing changes from dreamy or ecstatic to fiercely angry as he confronts Marguerite in her salon. He knows he’s gone too far, regretting his brutality as he turns aside in a moment the others miss.

Ferri has the advantage of Gary Avis as Armand’s father, rounding his role into a three-dimensional one instead of a silhouette. He, too, knows what he has done in breaking Marguerite’s heart and health. His distress in her death scene is as palpable as his son’s. By the time Ferri expires, reaching for heaven in Bonelli’s arms, Ashton’s melodrama has been transmuted into a tragedy by three superb artists.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

It had reverted, alas, to two dimensions in Natalia Osipova’s debut, with Valdimir Shklyarov (Mariinsky and Bavarian State Ballet) replacing Sergei Polunin as Armand. Osipova is young for the role as Ashton envisaged it; she doesn’t succumb to Armand’s ardour against her better judgment as a wordly, ailing woman. She’s enjoying herself with him until his father (Christopher Saunders, back to being a cardboard cut-out) spoils their country idyll. There is pathos in the way she bids farewell to unaware Armand as he sleeps, but she has none of the maternal anguish the older Marguerites reveal.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Shklyarov, handsome and elegant, understands his role but not the choreography. He does the steps, then adds the acting: a nice sequence of arabesques, then a hissy fit at her liaison with a rich old duke. He throws Marguerite and her diamond necklace to the ground, but shows no hint of remorse as he stands aloof. Osipova delivers a fine death scene, leaving him properly bereft, head in hands, but the ballet seems a preposterous extravaganza. At least this time round we’ve been spared the limp-haired wigs formerly inflicted on Marguerite’s admirers.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Different casts for the other two ballets in the triple bill bring different interpretations. In the opening night of The Dream, Akane Takada replaced Sarah Lamb as Titania, with Steven McRae as Oberon. Well-suited, they both seem imperious sprites, accustomed to getting their own way. McRae, magical at speed, lost focus when sustaining slow pirouettes into arabesque but kept regal control of his faery realm, including the foolish mortals who stray into it.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Takane’s Titania is spikily capricious, with amazingly pliable arms and feet. She’s erotically fascinated by Bottom as an obliging ass – so much so that in her reconciliation pas de deux with Oberon, she revels in her husband’s interest in her renewed sensuality.

Francesca Hayward as Titania is more of a wilful human princess, misled into an infatuation with a donkey she treats as a pet. Marcelino Sambé’s proudly feral Oberon is the consort she truly loves. She luxuriates in the music, daring him in their pas de deux to match her legato phrasing. She flings herself into his arms, then melts against his chest in complete surrender: delicious, as Antoinette Sibley was with Anthony Dowell.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Laura Morera is the most womanly of the three Titanias, spirited and loving. She brings out the wit in Ashton’s choreography, as well as its twisting waywardness. Alexander Campbell’s Oberon seems petulant rather than commanding. Though he can accomplish the trickiest of steps, he’s the wrong shape for a role made for Anthony Dowell’s long line. Luca Acri’s boisterous Puck threatened to overwhelm his master.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

David Yudes was the bounciest and most endearing of Pucks, his nonchalant shrugs provoking sympathetic laughter. All the lovers and rustics were funny, revelling in the theatrical gestures that Ashton sent up. Itziar Mendizabal’s pestering Helena was closer to farce than Olivia Cowley’s sweetly besotted girl, but their dilemmas are easily identifiable (as are their costumes, better than in the last revival). The fleet and silent-footed fairy attendants run so fast and stop so swiftly that they seem other-worldly, flitting on Mendelssohn’s music.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

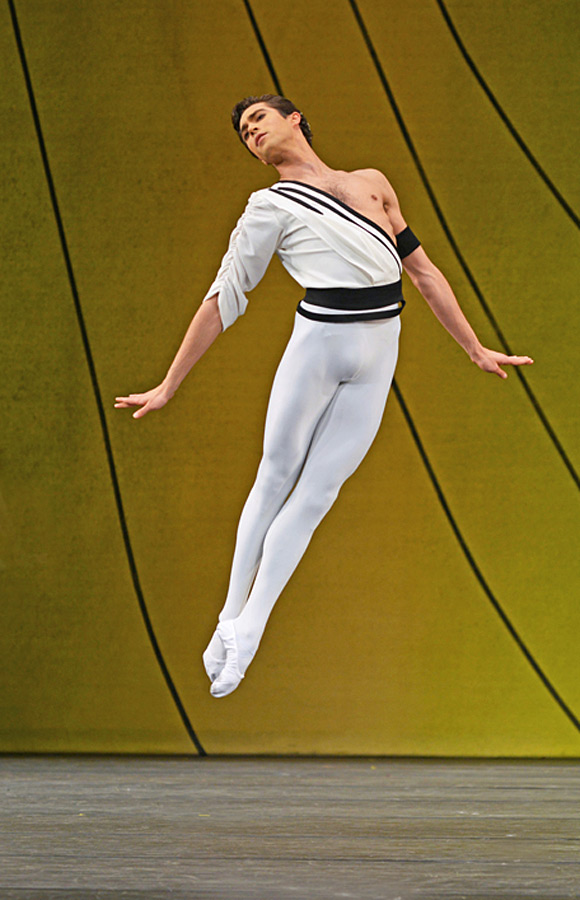

Ashton’s choreography, so conversational in The Dream, dispensed with narrative in Symphonic Variations to César Franck’s pellucid music. He refined his original ideas until he needed just six dancers on an empty stage, with a simple backdrop of curving black lines on a spring-green base. Casting and coaching are all-important: if anything is amiss, the spell is broken. At the first matinee, Reece Clarke’s one-shouldered top came loose early on; although backstage staff managed to fix it very discreetly, the performance never really recovered. Praise, though, must go to Joseph Sissens, making his debut in the Henry Danton role. His immaculate solo drew eyes away from Clarke’s brief absence in the wings.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Sissens and James Hay in the evening cast both accomplished the head-flung-back pirouettes that were Danton’s speciality. Yasmine Naghdi as one of the ‘side girls’ was also a joy to watch. Most impressive were Vadim Muntagirov and Marianela Nunez as the central couple, ‘waiting in the music’ – a quote from Violette Verdy in Ismene Brown’s excellent programme note. They keep absolutely still until their turn comes to join in, unassuming but owning their place at the heart of the ballet.

© Tristram Kenton, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Ashton knew the power of a turned back, tantalising the audience. (Armand makes his entrance in Marguerite’s salon with his back to us.) Muntagirov calmly asserts himself long before he turns round, flanked by his two companions. He serves his three graces unobtrusively, lifting them gently as the piano notes rise and descend. Symphonic Variations is a reminder of the beauty of skimming lifts and low arabesques, tilted heads and subtle épaulement. Towards the end of 20 minutes of rapture, the central man erupts into virtuoso entrechats and double tours en l’air. There should be no need for smiles because his exultation is obvious. He is assimilated into the chain of equals, circling the stage with linked hands as though the dance would go on forever.

fine writing and keen observation and analysis. Bravo.

Many thanks for this most insightful review – brings into focus hugely enjoyed performances over the last week or so.

Thank you for your kind words. But my mistake: the originator of the head-thrown-back pirouettes in Symphonic Variations was Brian Shaw, not Henry Danton.

I forgot to mention that I have an indelible memory of Zenaida Yanowsky at the Jackson Competition where she won the Junior Women’s Gold and her brother got the Senior Men’s Silver. [I may even have mentioned it in a ballet.co dispatch] They collaborated in a contemporary pas de deux, an image of which I recently found in my various piles of souvenirs. It was quite an exciting event, and subsequently I have read avidly about her roles with The Royal, particularly loving her Red Queen. What an artist.

Brilliant reviews of the ballets we enjoyed last week. I shall return to this website frequently.