© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Kenneth MacMillan: a National Celebration

Royal Ballet: The Judas Tree

English National Ballet: The Song of the Earth

★★★★✰

London, Royal Opera House

24 October 2017

Gallery of Judas Tree pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

The second programme commemorating the 25th anniversary of Kenneth MacMillan’s death revealed his very different responses to music, and to human nature. The Song of the Earth, to Mahler’s final song-cycle, tells of young people’s eventual acceptance that their lives will end; in The Judas Tree, death is a brutal sacrifice, the consequence of jealousy, rage and betrayal.

Brian Elias wrote his score for The Judas Tree after many discussions with MacMillan about its themes. Elias came up with an outline scenario, giving timings of the music and mentioning the instruments used – steel pans, a cowbell, brass, strings, woodwinds, a vibraphone. MacMillan went his own way, developing a narrative that combines gnostic mysticism with contemporary realism.

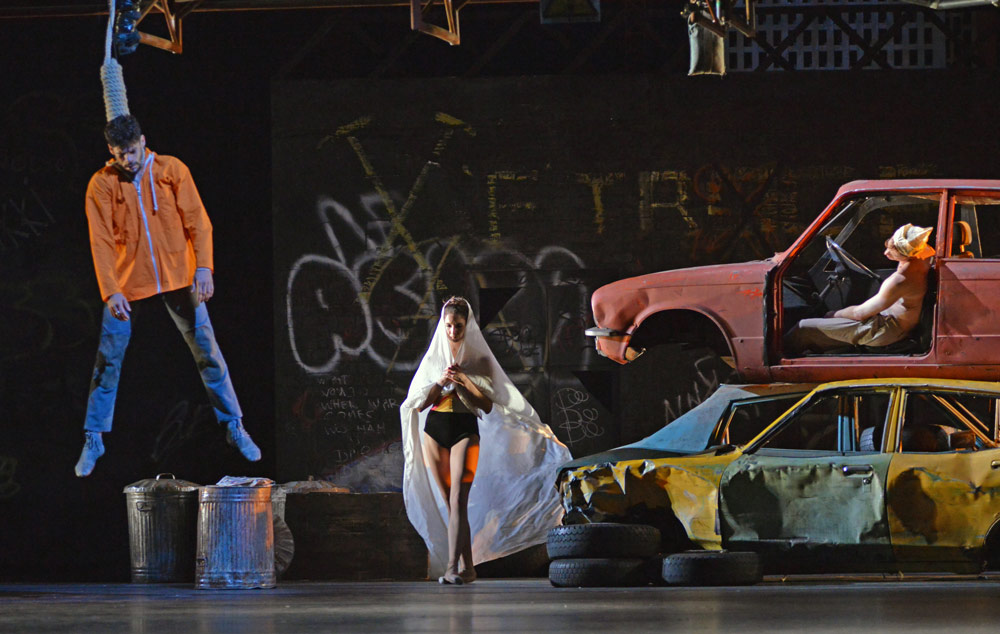

The 14 men, construction workers on a London building site, are at the same time biblical figures, like those in a religious painting where the participants wear their own clothes, not those of early Christian times. The act of betrayal is the Judas kiss. MacMillan took it for granted that 20th century audiences would recognise his use of Christian imagery (as he does in Gloria, Requiem and Different Drummer). Many 21st century audience members might not be familiar with New Testament gospel stories and iconography. In which case, can The Judas Tree really only be seen as a violent account of murder, rape and lynching?

The sole woman, who might seem to be a victim of male brutality, is immortal. She appears to die three times, but she is still alive at the end of the ballet. She is Mary, Magdalene and Madonna, Eve and Lilith. In earlier ballets, such as Le Baiser de la fée and Images of Love, MacMillan established dual female characters, pure and wanton. Then he combined them as Manon and Mary Vetsera. The woman in The Judas Tree, however sexually provocative, is ultimately undefiled. She survives rape and murder, shrouding herself with a veil of purity.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

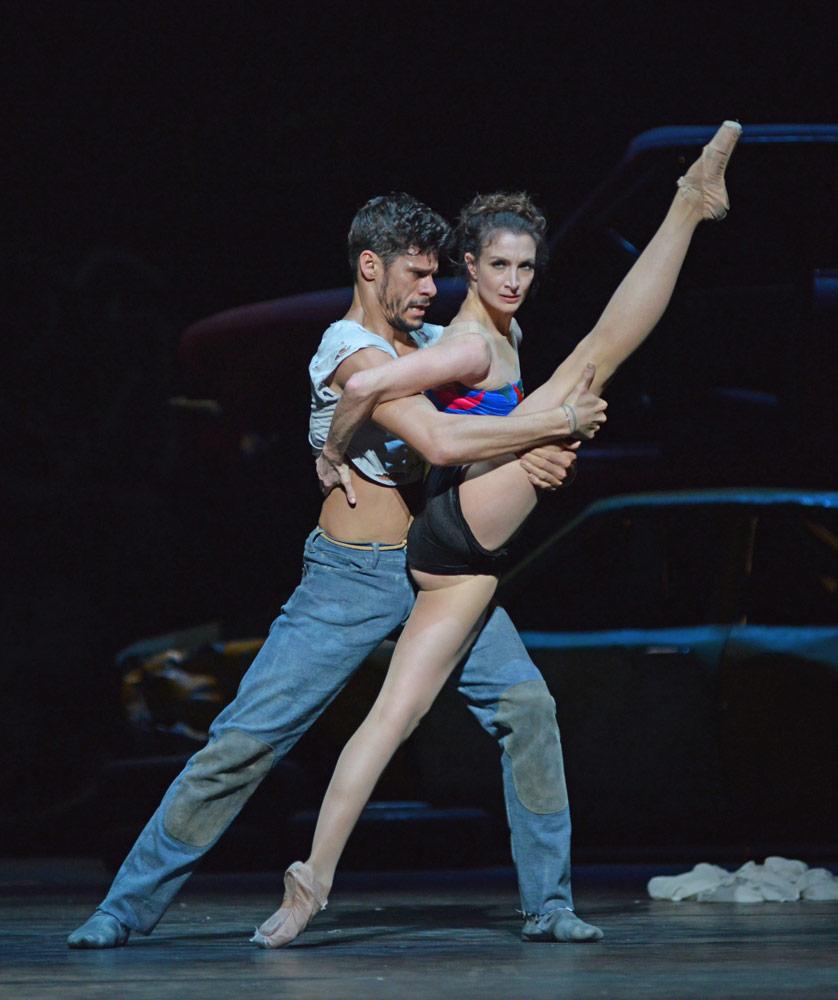

Lauren Cuthbertson as the woman owns her sexuality, claiming the right to walk over the backs of the men on the building site. She is nominally the girlfriend of the Foreman, Thiago Soares, but she treats him with seductive contempt, taunting him, as she does the other two principal men, Edward Watson (as Jesus) and Reece Clarke (as Peter). Cuthbertson flaunts her long legs like weapons, flicking a man’s chin or pawing his crotch. This is an aspect of her theatrical personality she hasn’t had the opportunity to reveal before, very different from her girlishness as Alice in Wheeldon’s Lewis Carroll ballet.

Soares doesn’t have the physical heft or dominating presence of Irek Mukhamedov as the Foreman, so the ballet’s power balance shifts between the characters. The Foreman appears vindictive, lashing out to disguise his insecurity; he is resentful of the Jesus character’s closeness with Mary – at one point, Watson shelters with Cuthbertson under her protecting veil. Jesus has to save her from herself, and from her ‘death’ at the hands of psychotically disturbed Judas. Soares is convincing in his reading of a man tortured by inner weakness.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

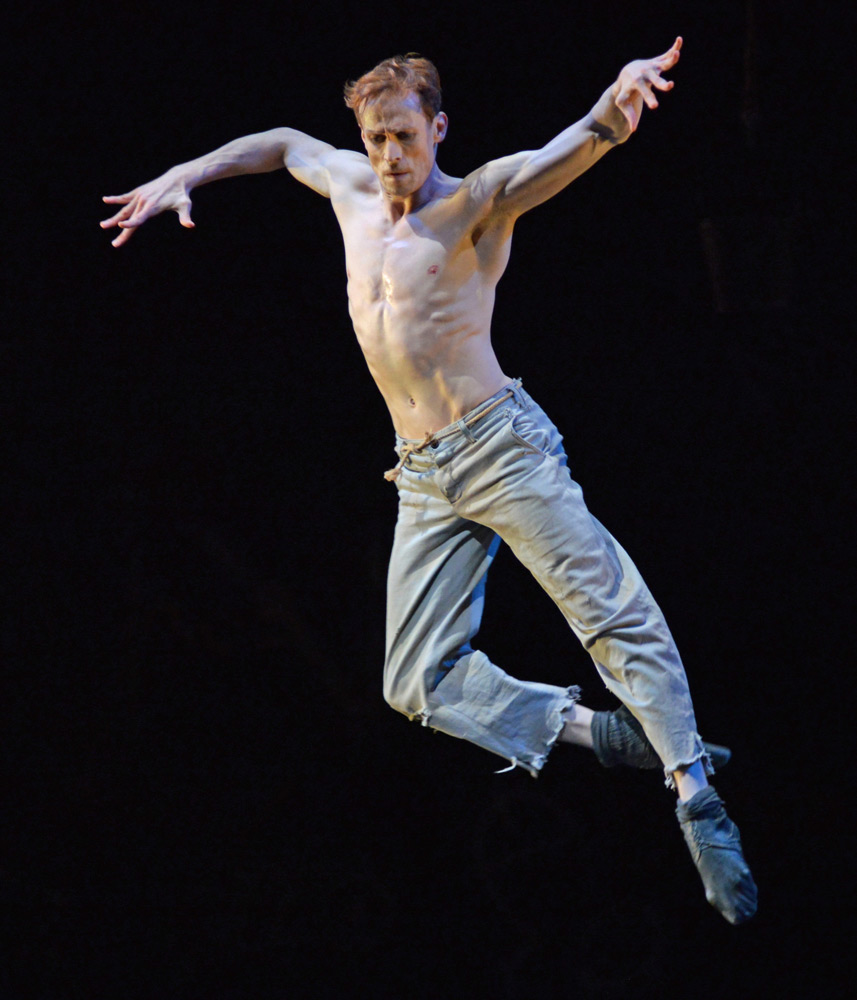

Clarke as Peter is also conflicted, desiring the woman he can’t have, and having to witness her violation. Because Clarke is so tall, he is always noticeable, lurking in the scaffolding of the set as a witness. (Nobody is ever alone, unwatched.) He has an extravagant solo of leaps and anguished arabesques, as Watson runs around him, suspecting he can’t be trusted. Peter will fail him, and Mary. Peter has to carry off Mary’s shrouded body after he has seen her being gang-raped; he knows that Judas has blamed Jesus for her murder; he stands by, helpless, when Jesus is lynched by the gang. It’s a painful humiliation for a big man.

Watson’s role as Jesus comes more to the forefront of the ballet because Soares’s Foreman is not overpowering. Pale and tormented as only Watson can be, he cannot prevent the atrocities in the ballet. He can resurrect Mary but can’t prevent his crucifixion by the mob. At the end, his body is placed in an abandoned car, his sepulchre, with a mocking paper hat on his head. Mary comes to stand by him, the lights on the Canary Wharf tower winking above them.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The music has driven the action, culminating in Judas’s suicide. Its savagery sounds both modern and ancient, harsh and mysterious. Elias has built in the tension between the characters in a series of jagged variations, ending without resolution in a silence that leaves the audience in shock.

The ending of The Song of the Earth is one of the most heart-stirring in all ballet, with its promise of eternity to Mahler’s repeated ‘Ewig…Ewig…for ever and ever’. English National Ballet has brought its touring production to the Royal Opera House stage for the MacMillan celebration, with its own conductor, Gavin Sutherland. Principal coaching credits are shared by Tamara Rojo, ENB’s artistic director, and Edward Watson, both of whom have danced the ballet many times.

Tamara Rojo and Deborah MacMillan on the importance of Mahler's music in Kenneth MacMillan's #ENBSong, which opens at @MKTheatre tonight. pic.twitter.com/1nosWyBdKD

— English Nat'l Ballet (@ENBallet) October 17, 2017

For the first night, the role of the principal woman was taken by Erina Takahashi; the principal man was Isaac Hernandez and the Messenger of Death was Jeffrey Cirio, a guest from American Ballet Theatre. The role of the Messenger has been interpreted in different ways, as an unthreatening figure or a commanding one. Cirio makes him assertive, a dark angel but not an imposing one, since he is relatively slight in height.

MacMillan did not originally intend the Messenger to be conspicuous. He was called Der Ewiger, the Eternal One, in the first Stuttgart Ballet production; although he wore a colourless half-mask, his all-in-one outfit was not ominously black. In subsequent productions, the role has become more like Death itself. And dancers such as Rudolf Nureyev or Carlos Acosta could hardly help being noticeable.

Cirio fits in with the larky lads of the lyrics, translated from early Chinese poems. He becomes briefly sinister as a crouching monkey in the first song, but reverts to appearing a jolly drunkard in the fifth: he’s faking it, as its disconcerting last moments reveal. By the long Farewell, he is relatively benign, reuniting the woman with her lost lover. Hernandez is immensely sympathetic as the man, taken too soon.

© Laurent Liotardo. (Click image for larger version)

Takahashi makes her presence felt as the lonely one in the second song, more special than her girl friends, Senri Kou, Tiffany Hedman and Alison McWhinney. They dance charmingly in songs of youth and beauty, but Takahashi knows that she is the Messenger ‘s chosen one. She accepts the inevitability of her fate, drifting on pointe like an autumn leaf, impelled by the music.

The singers, Rhonda Browne and Samuel Sakker, at the sides of the stage, are an important part of the ballet, as are the words of the songs, printed in the programme. Because the choreography follows the sense and imagery of the lyrics so closely, the ballet can pall without that knowledge. Though ENB’s cast dance it faithfully, they find too little variety in the energy of the contrasting songs to keep it from seeming soporific after the ferocity of The Judas Tree.

You must be logged in to post a comment.