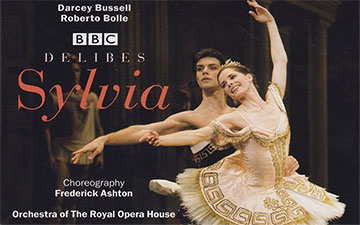

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Sylvia

★★★★✰

London, Royal Opera House

23 November 2017

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

The basic plot of Frederick Ashton’s Sylvia (1952) bears a strong similarity to that of his Daphnis and Chloe (1951). As David Vaughan pointed out succinctly in his study of Ashton’s work, Frederick Ashton and his Ballets: ‘Both ballets have an ineffectual hero who does nothing to save the heroine from a fate worse than death; instead he passes out and the rescue has to be made by a deus ex machina.’

Both are pastoral ballets, set in an Arcadia populated by nymphs and shepherds who believe loyally in their local god. Ashton and his designers, the Ironside brothers, transplanted Sylvia from Greece to Second Empire France, close to the period of the original ballet by Louis Mérante, with its score by Leo Délibes (1876). Ashton chose not to update the libretto, based on a play by the 16th century poet Torquato Tasso.

The attraction is not the implausible story but the music, irresistibly dansant. The enticing overture promises treats in store – promises that are mostly fulfilled. We have to put up with a lot of frolicking at the start by frisky woodland creatures and merry country folk bearing agricultural tools. But then comes an exquisite solo for the shepherd Aminta, musing on his passion for Sylvia, the leader of Diana’s huntresses, all sworn to chastity.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Vadim Muntagirov, full of grace, dances like a classical vision, finishing his slow arabesque turns in a plunging pencheé tauter than a huntress’s bow. As soon as he hears the horns heralding the hunt, he hides behind the statue of Eros, leaving his cloak behind. Sylvia is seen on the ironwork bridge crossing the bosky grove, before entering with her Amazonian attendants. Marianela Nunez starts out as an athletic toughie, intent on dancing ahead of the music. She didn’t seem to trust the conductor, Simon Hewitt (now with the Hamburg Ballet) to determine the tempi until Act III, when she was visibly more at ease.

Her cohort of helmeted huntresses had problems timing their flurry of leaps. Strapping as some of them are, they can’t move fast enough for Ashton’s speedy steps. Transformed into girlish celebrants in Act III, they looked flustered in a group dance that resembles the ballabile for stars in Cinderella. Maybe this season’s transition from recent works to Ashton in 19th century mode has been too demanding for the start of this revival.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Aminta is duly discovered, thanks to his discarded cloak. In a confusing business with arrows, Sylvia shoots him while aiming at the statue of Eros (Valentino Zuchetti, excellently static up to this point) and gets pierced in return. So now she’s in love with Aminta, who’s dead. She gets abducted by evil Orion (Thiago Soares), who has been lusting after her, and Eros resuscitates Aminta. Zuchetti has fun disguising his white marble physique with a cloak and sun hat as a quirky sorceror. As Ashton noted, Délibe’s tune for Eros is a silly one, so he made him into a capricious love god. Could it be that Eros is fonder of Aminta than Sylvia, who tried to shoot him, and that’s why he goes to such efforts to make Aminta happy?

Act II becomes very silly. Orion in his lair has two comic slaves (Kevin Emerton and David Yudes) and two bewildered concubines (Romany Pajdak and Leticia Stock). In the original libretto, according to Cyril Beaumont’s Complete Book of Ballets, Sylvia makes wine by pressing grapes into an amphora. Unaccustomed to alcohol, Orion and his entourage soon become drunk, while Sylvia dances distractingly. Ashton has Sylvia encouraging Orion to swig from his already copious supplies. Nunez reveals her naughty side as a vamp, always in command of the situation. Soares can only glower, clad in a preposterous piratical costume. (When Arthur Pita cast him as a non-villainous character, for once, in The Wind, Soares was unrecognisable, alas.)

Eros comes to Sylvia’s rescue with a handy ship, very like the Lilac Fairy’s boat. He shows Sylvia a vision of lovelorn Aminta, alive but asleep, awaiting her at Diana’s temple. He is supposed to be worn out by searching for his lethal beloved: we have to take that on trust. By this stage, however, we might as well succumb to Ashton’s vaudeville middle act, with the transformation scene that the Royal Ballet could never afford during his lifetime.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Act III has been trimmed of additional music from Délibes’s ballet score for La Source. It was included to provide divertissements for gods, nymphs and muses honouring Bacchus – a celebration that would make more sense if Sylvia had saved herself from Orion by creating instant wine. As it is, the triumphal parade of visiting deities looks like The Sleeping Beauty assembly of non-dancing fairy tale characters. Two goats, due to be sacrificed to Bacchus, survive to prance, recalling Petipa’s pussy cats as well as Nijinsky’s faune.

Eros finally gets his chance to show off his prowess as a classical dancer once he has united Aminta and Sylvia. Their pas de deux more than justifies the three-act revival of the ballet. It depicts a divinely human love story in which the modest shepherd becomes heroic and the arrogant nymph abandons herself to him. Their entry, with Sylvia, lifted high, half-kneeling on Aminta’s shoulder, recalls the magical arrival of Pan with rescued Chloe in Daphnis and Chloe.

Nunez summons up all the radiance she can beam from Muntagirov’s arms, including flinging herself into them in a daring dive. (Ashton apparently added it after seeing the Bolshoi’s first visit to London in 1956.) She’s delightful in the pizzicati solo, at last playing with the music. Muntagirov floats his ecstatic leaps around the stage in Aminta’s variation, made to show off Michael Somes’s improved technique after training in Paris with Alexandre Volinine (according to Vaughan.) Muntagirov brings Nunez’s head between his hands to rest on his chest – a tender gesture lost when Sylvia is a tall dancer, like Darcey Bussell or Zenaida Yanowsky in an earlier revival.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Their idyllic affair is thwarted by Diana, goddess of chastity – Itziar Mendizabal in a fury of rage. She sees off Orion with an arrow, then turns on the illicit lovers. Eros reminds her with a tableau vivant that she, too, was once infatuated with a shepherd, Endymion (another unconscious male love object). Délibes’s music softens, as it did for Aminta’s opening solo, implying that shepherds are purer than unreliable deities. All ends happily, in general rejoicing against a splendidly opulent setting.

Sylvia makes a welcome return to the repertoire, reacquainting dancers and audiences with Ashton’s sensibility and complex choreography. It’s a joy but not a masterpiece, as he well knew – he kept trying to restructure it. The men in the ensembles are badly served with twee steps and a lot of standing about. Aminta is a passive hero and Orion a stock ‘oriental’ villain. It’s a ballerina vehicle, designed to display Margot Fonteyn at the height of her powers, with no supporting roles for female soloists. Nunez has matured into a multi-faceted Sylvia since her debut back in 2004, but she was still pushing too hard in the first act on the first night of this revival. Natalia Osipova and Lauren Cuthbertson are due to follow, with Federico Bonelli and Reece Clarke as Aminta. The huntresses, dryads, naiads, demi-gods and peasants have plenty of chances to polish their ragged routines to give the production a convincing patina.

You must be logged in to post a comment.