© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Paul Taylor American Modern Dance

22 March: Dances of Isadora, Concertiana, Promethean Fire

25 March: Musical Offering, Runes, Mercuric Tidings

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

22, 25 March 2018

ptamd.org

davidhkochtheater.com

If given the task of casting a contemporary ballerina in Isadora Duncan dances, Sara Mearns is likely to come up as a viable candidate. The great thespian of City Ballet, Mearns is known for impassioned, hell-or-high-water performances full of verve and sensuality which push the limits of drama and technique. As part of Taylor’s continued commitment to showcase work of American modern dance icons, Mearns got to sink her teeth into Duncan in several performances of Paul Taylor American Modern Dance’s Lincoln Center season.

But can a classically trained ballerina do Duncan justice? Ashton certainly thought so when he created Five Brahms Waltzes in the Style of Isadora Duncan for one of the 20th century’s most intuitive and dramatic ballerinas, Lynn Seymour. Rumor has it, Marie Rambert – whose career in dance is attributed to seeing Duncan live – burst into tears when she saw Seymour’s interpretation. Lori Belilove, today’s pre-eminent Duncan interpreter, set 10 dances on Mearns. Dating from 1920-1924 the dances are set to Chopin waltzes, mazurkas and etudes, a few Brahms’ waltzes and Liszt.

The suite opens with Cameron Grant seated at a piano onstage, and Mearns on a small riser. He plays Chopin’s mournful prelude in E minor, and Mearns sways softly from side to side in a Hellenistic swathe of tangerine pink. In Narcissus Waltz she skips and flings her limbs freely, but the result is awkward, her body torn between turnout and parallel, flat feet and demi-pointe, and lacking the soft/nimble duality that Seymour embodied – a combination of pagan earthiness and the sharp lightness of a sprite. Duncan’s aim was never to be pretty, however there is a stiffness in Mearns that begs the question: what would Duncan look like on a Mark Morris dancer?

© Rose Eichenbaum. (Click image for larger version)

After the Loie Fuller number (Butterfly Etude), she turns a corner with Harp Etude (both Chopin). Pushing her arms out in front of her, her hands lightly tread and push away the piano’s twinkling ripples, as if swimming through music. Mearns loses herself, and one sees the transcendent channeling of music, the dreamer and dancer merged in a sacred rite. One of Duncan’s specialties was personifying rather than reacting to the music, and Mearns achieved that unification here.

She channels Giselle and Ophelia in Death and the Maiden, her gaze changed, as if the “outside” world has ceased making sense, and the choreography – weighted and inclined towards rather than away from the underworld – suits the slow, sultry Chopin mazurka. Les Funerailles, a broody lament, we see Duncan as the precursor to Graham, with Mearns all but concealed in sculptural draperies.

With the rose petals, bare breasts, and primal revolutionary fervor, it is easy to parody Duncan (as the Trocks have often done to high acclaim). Though Mearns came into her own halfway through, she often remains balletic. But by staging Duncan on one of today’s ballet darlings, at Balanchine’s theater, in the 21st century, Paul Taylor is really trying to tell us that dance’s past is also our present and our future.

Duncan today looks simultaneously timeless, dated and pioneering. Despite the desire in modern and contemporary dance to shed shackles of ballet’s filigree and pomp, in many ways today’s more conceptual choreographers have added new layers of complexity that can be far removed from how most humans define dance: as an instinctive relationship between movement and music/rhythm. With Duncan, no ambiguity of what one is watching exists: it is dance distilled. There is no DNA being mined here, no deeper concept to unpack. Most human relationships to music and dance are impulsive. Duncan’s approach might have been affected, but it was not thoughtless: her talent to create choreography that appears improvised was one of her greatest gifts and what makes her work still appear refreshing to us today.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Taylor’s Promethean Fire from 2002, a “classic” of his later works, is yet another example of Taylor’s mastery of Bach. Using Leopold Stokowski’s orchestrations of the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, the Prelude in E-flat minor, and Chorale Prelude BWV 680 (performed by the Orchestra of St. Luke’s), Taylor takes the audience on a ride from hell and damnation to heavenly redemption. The timing of the work’s debut, post-9/11, makes it easy to read the piles of bodies a certain way. The Toccata and Fugue finds dancers creating order amidst chaos, proving a tour de force of Taylor’s ingenious sense of structure. Formation after different formation – concentric circles, overlapping circles, weaving X’s, spiraling bodies moving in lines – ebb and flow seamlessly. Dancers are grouped into duets, trios and quartets with enough asymmetry to pique interest but not disrupt the flow or Bach’s mounting intensity. Taylor’s dancers move with ferocious commitment, never timid, but never overdone. Even in stillness, Taylor dancers hold immense power in their bodies, the energy potential within them more nuclear than solar.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Fire also overshadowed Taylor’s newest work, Concertiana. Using music by Eric Ewazen, Concertiana is a buzzing hive of activity full of Taylor’s classic vocabularic motifs, but the complete package is a bit of a blurry haze, rather than a work that feels definitive.

On Sunday a trio of Taylor classics closed the Lincoln Center season. Two somber works – Musical Offering and Runes – were performed back to back before the joyous Mercuric Tidings.

Although Musical Offering draws aesthetic inspiration from New Guinea statues, the work – with sets and costumes in sandy, clay colors – looks more 2d than 3d. Flat hands, robotic rocking movement, and frieze-like poses are the core aesthetic, set to Bach’s eponymous music composed for King Frederick the Great and used by Taylor as a requiem. Challenging at times beyond belief, Taylor’s dancers don’t let him down. In one section Michelle Fleet never touches the ground. Held aloft by several men, she rolls her body in slow somersaults or cartwheels all atop their shoulders. In another segment, Robert Kleinendorst leaps into handstands and completes a difficult series of repetitious jumps – one can almost feel your own heels hurting as you watch him.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

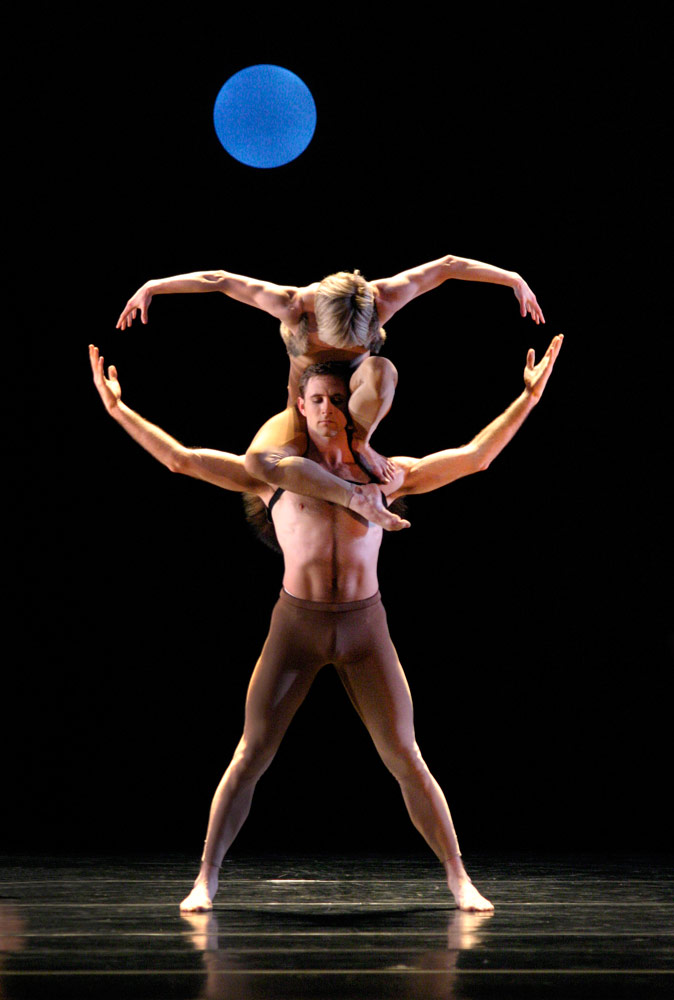

The challenges continue in the 1975 work Runes, which is notated in the program as “secret writings for casting a spell.” A moon slowly moves across the backdrop of the stage as dancers conjure flames and cast spells over each others bodies to piano music by Gerald Busby. Runes sees Michael Trusnovec carry two women across the stage at the same time, he also catches Parisa Khobdeh’s flying body as if bolted to the ground, not re-adjusting an inch. Thematically it sounds goofy, but Runes is a serious Taylor work chock full of physical feats only his dancers can do.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Despite their formal mastery and demanding steps, Musical Offerings and Runes both lose out to Mercuric Tidings for sheer visual and aesthetic pleasure. Donning bright tulip pink costumes and lit by Jennifer Tipton’s sunny lighting, the dancers dart around to excerpts of Schubert’s first and second symphonies with an energy akin to Esplanade. Tidings is chock full of brisk petite allegro, spiraling turns, and beaming smiles. Dancers offer each other the stage with polite waves and gestures of the hands, as if to say “after you.” While not as crisp as his formal structures around Bach, Taylor’s musicality finds ways to help us see his choreography and hear Schubert anew.

Thanks for this terrific review. Your description of Mearns especially is very evocative and makes me feel almost as if I had seen the performance. I’m a huge Paul Taylor fan and was sorry not to have been there.