© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Bernstein Centenary: Yugen, The Age of Anxiety, Corybantic Games

★★★✰✰

London, Royal Opera House

15 March 2018

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

Leonard Bernstein wrote (in 1949): “I have a deep suspicion that every work I write, for whatever medium, is really theatre music in some way.’ Many choreographers have taken up the challenge, though his quasi-metaphysical musings have usually eluded them: dance is more corporeal than music.

The Royal Ballet’s triple bill commemorating the centenary of Bernstein’s birth requires a lot of information in advance, from the meaning of the ballet titles to the inspiration for the music. Programme notes are essential reading, as is the internet (for titles); cast sheets provide translations of Hebrew psalms for Wayne McGregor’s Yugen, though the sung words are unintelligible. Fortunately, for anyone who hasn’t had the time to do their homework, the three ballets look good and are excellently danced, sung and played.

Yugen, as spelt, means little to Japanese speakers unless it’s written in kanji ideograms (幽玄). It is untranslatable, other than to imply the evocation of beauty through simple means. The music is Bernstein’s setting of six psalms, commissioned by the Dean of Chichester Cathedral in 1963 and henceforth known as the Chichester Psalms. These songs of exile range through exultant to troubled to faith-affirming. Hebrew is very flexible as a sung language, so Bernstein was able to recycle music he had composed for an aborted musical, The Skin of Our Teeth (no wonder it’s danceable).

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The set, commissioned from writer and ceramicist Edmund de Waal, consists of four tall vitrines, display cases hovering above the rear of the stage. At the start and end they house dancers in silhouette, figurines witnessing the actions of their peers. All eleven dancers are dressed by designer Shirin Guild in loose fitting costumes in shades of red. They are a tribe of individuals and eventually heavenly beings.

McGregor has modified his angular, contorted choreography into smooth flowing surges of movement, with bodies winding around each other. A duet for Calvin Richardson and Sarah Lamb resembles ice-dancing as she is swept across the stage in straight leg lifts. When Federico Bonelli joins in, hyper-supple Lamb is manipulated between and over them as if she’s a swathe of fabric. Perhaps she is a vision, for she never acknowledges her partners.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Richardson is the main protagonist, a man apart, walking through the valley of the shadow of death. He has a tense, inward-curving solo, twisting and rising, as a boy treble (William Davies) sings the 23rd Psalm. When male voices sing of conflict, male dancers hurl each other about. They join forces to support Richardson for Psalm 131, as he humbles his soul before the Lord. Joseph Sissons appears to be his consoling angel in the final section, which bears a resemblance to Kenneth MacMillan’s Requiem.

McGregor doesn’t do linking steps in his choreography. He moulds and articulates bodies, relying on paces and lunges to get his cast from one shape to another. In Yugen, the circular, wave-like motion, amplified by swirling costumes, becomes indulgent. Without his trademark fragmentations, it’s as if he’s run out of vocabulary, relying on Bernstein’s vocal lines to make the dancers look lyrical.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Christopher Wheeldon, whose Corybantic Games ends the triple bill, can draw on a lexicon of ballet steps and an encyclopaedia of choreographic invention. He has used Bernstein’s Serenade violin concerto before, as a young choreographer for Boston Ballet in 1999. Now he has tackled it in maturity, using a similar title – Corybantic refers to ecstatic dances performed by acolytes of a Phrygian mother of the gods, Cybele. Bernstein’s inspiration was Plato’s Symposium, in which different speakers discuss the nature of love. Each of the five movements of the work, in seven sections, evolves out of the preceding one, referring to the interlocking friendships of the Athenian speakers.

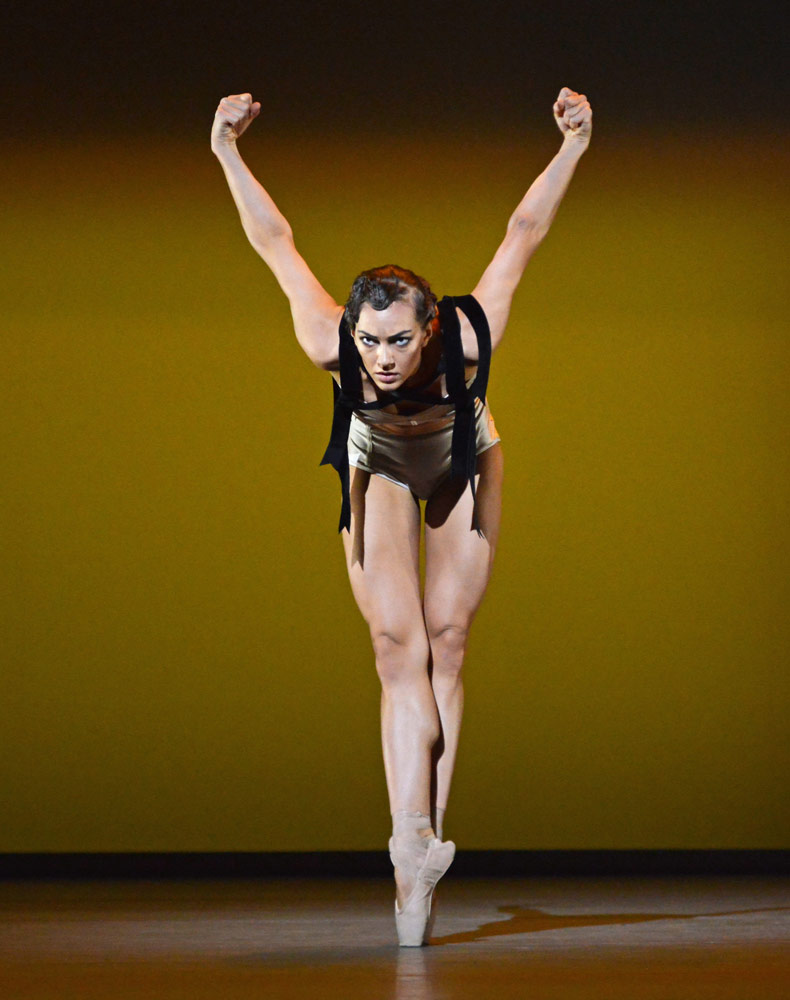

Jean-Marc Puissant’s changing structures suggest elements of an Ancient Greek temple. Erdem Moralioglu’s costumes make the men look almost nude, like Greek statues of naked young men; the women wear 1950s style corsetry, with long pleated tulle skirts that they discard half way through. Black velvet straps indicate the status of soloists and demi-soloists among the cast of 21. Much publicity has been given to Erdem’s contribution, with preview articles in Vogue and the New York Times. Members of the fashion press were invited to the opening night. Yet the costumes seem hardly worth the fuss. Boned bustiers and big knickers look clumsy on slender female bodies and velvet ribbons flutter distractingly. The men could be wearing gaffer tape stripes on flesh-coloured vests above standard white tights.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Sergey Levitin, Co-Concert Master of the Royal Opera House Orchestra, played the solo violin part Bernstein wrote for Isaac Stern. The violin introduces the first two roles, the lover and the beloved – Matthew Ball and William Bracewell, youthful and elegant. They are joined by their female counterparts, Lauren Cuthbertson and Yasmine Naghdi, before the first movement becomes a rite for male athletes. It ends with the men on their backs, feet flexed in the air like the leaves of seedlings.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Beatriz Stix-Brunell has a quixotic, luscious solo to pizzicato strings in the second movement. She is joined by six playful maidens in long skirts; linked together, they resemble the combinations in Balanchine’s Serenade, then a group tableau from Nijinska’s Les Noces. In the fourth movement, Stix-Brunell and Naghdi dancing closely together are very evidently based on the grey girls in Nijinska’s Les Biches. Their pairing is one of three simultaneous duets illustrating different aspects of love: Ball and Bracewell are the other side couple, with Cuthbertson and Ryoichi Hirano in the centre as the heterosexual pair. Their duets are different but connected through the shapes they make and the intimacy of their emotions. It is a beautiful polyamorous sequence.

There’s been a brief interjection by a pair of playmates, Mayara Magri and Marcelino Sambé, rivalling each other in speed and exuberance. They could have come from Balanchine’s Rubies, with supported runs for her from an Ashton ballet. After just a minute and a half, she is thrown into the wings, to the delight of the audience. Wheeldon rehearsed Magri and Sambé for an Insight evening in which it was revealing that he used musical counts, whereas McGregor relied in his rehearsal on clicks and grunts. Wheeldon analyses music; McGregor doesn’t.

The fifth and final section of Corybantic Games features an Amazonian woman, Tierney Heap, presiding over Corybantic revels. She summons a female retinue, like Myrtha in Giselle, then commands the massed corps to boisterously jazzy music that sounds very like West Side Story. Couples come and go, a frieze of dancers crosses behind Tierney’s exertions, others interweave and reunite until at last the celebration ends. So much is going on that the evening ends in exhaustion.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

It hasn’t helped that the middle ballet is a revival of Liam Scarlett’s 2014 attempt at The Age of Anxiety, based on W.H. Auden’s wartime poem of that name. Bernstein composed a symphony around its themes and characters, described in detail in the programme note but without a synopsis in the cast sheet for the ballet’s action. The age of anxiety, it seems, is ‘the precarious co-existence of freedom and necessity, the perpetual interplay of boredom and horror, which can only be navigated by embracing our shared humanity.’

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

What we see on stage are four crudely characterised people, three men and a woman, who drink in a New York bar, get drunk in an apartment and end up in various unsatisfactory states of mind, apart from one who experiences an apotheosis as dawn rises over Manhattan. We don’t know their back stories or the philosophical dream journey in seven stages on which Auden and Bernstein take them. Scarlett’s choreography treats them as musical comedy types, dancing in unison as a quartet, with brief balletic solos to distinguish their inner anguish. Only Bennet Gartside elicits any sympathy as a disaffected businessman with revealing touches of vulnerability. What Tristan Dyer’s dreary character, Malin, has done to deserve a transcendent finale remains a mystery. John Macfarlane’s sets are spectacular, which must be why this dud of a ballet has been revived – and, of course, Bernstein’s symphonic poem.

You must be logged in to post a comment.