© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet

Voices of America: Playlist (Track 1, 2), Approximate Sonata 2016, The Cage, Fantastic Beings

★★★★✰

London, Sadler’s Wells

12 April 2018

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.ballet.org.uk

www.sadlerswells.com

The centenary of Jerome Robbins’s birth is being celebrated by English National Ballet (ENB) with a production of his 1951 mini-melodrama, The Cage. Robbins’s ballets are relatively little known in Britain: the Royal Ballet has performed only seven out of the 64 he created. New York City Ballet, where he choreographed alongside George Balanchine, will be performing six programmes with 21 ballets in his honour in May.

For the rest of the programme she has called Voices of America, Tamara Rojo revived a 2016 piece by Canadian Aszure Barton, Fantastic Beings, and invited William Forsythe, now living back in the States, to work with ENB. It’s very much a mixed bill, in which The Cage comes off worst and Forsythe’s new creation scores a hit – a coup for the company.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

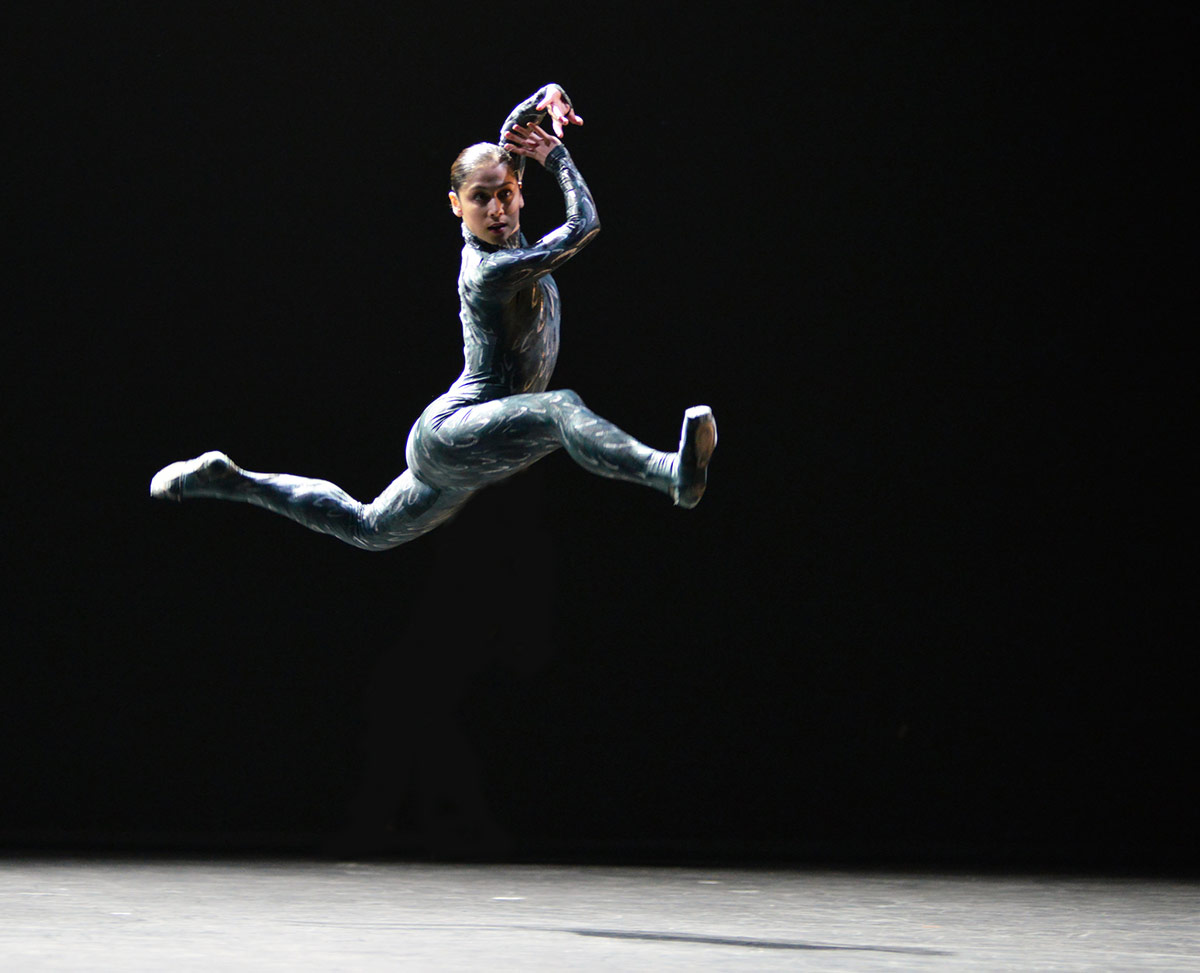

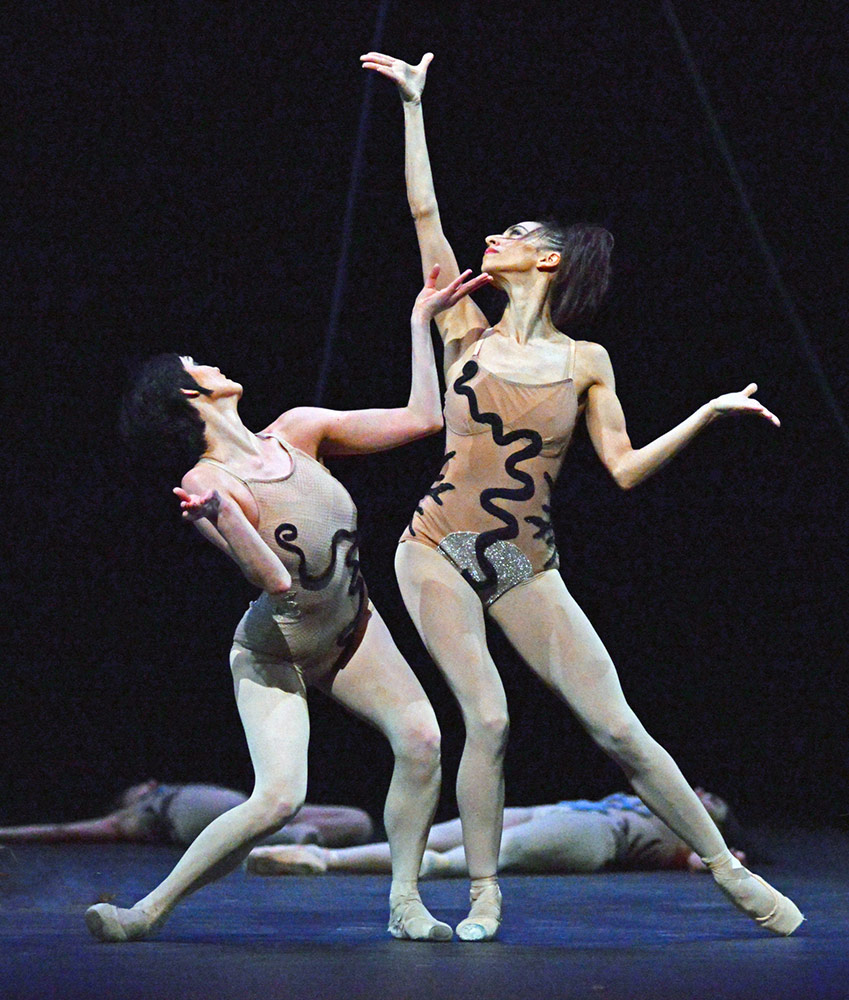

Forsythe treats the dancers as super-human athletes. Robbins and Barton make them less-or-other-than-human – insectoid, primal. When a choreographer wants to expand her or his way of working, going for animal, avian or insect movements is an obvious option: hands become claws, pincers, antennae; bodies undulate, crouch and spring.

Barton takes this route in Fantastic Beings, to music by Mason Bates entitled Anthology of Fantastic Zoology, inspired by a bestiary of stories by Jorge Luis Borges. Twenty dancers enjoy themselves, picked out in solo spots, duets and small groups, or swarming together like militant insects. Balletic steps are interspersed with squats, scuttles and crawls, legs flying up on a blast from the orchestra. No sequence lasts for long: romantic mating duets are interrupted by an intruder; random figures run or amble across the back; a hairy beast knuckles its way across the front of the stage.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

There’s no apparent structure, other than one quirky number following another for a different combination of dancers. The music keeps promising dramatic climaxes that come to nothing. In one of many false endings, a cohort of creatures run on, to stand facing a projected eye. They squat in obeisance but then carry on into yet more spinning and leaping routines. Gradually, more and more lycra-clad dancers are transformed by orangutan costumes into identical beings, fringes flying as glitter falls from the flies in a long-postponed finale. Borges ended his bestiary with all his mythical creatures fused together. What, if anything, Barton’s fantasia signifies is a mystery.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

The import of The Cage is all too clear. An early critic, Walter Terry, described it as ‘a rite of blood and destruction and eternal hate’. In the 1950s, Robbins was experimenting with making ballet as modern as Martha Graham’s contemporary choreography. By turning 14 female dancers into a hive of insects instead of a corps of Wilis, he could create strange angular shapes and clusters of bodies. The results no longer look radical, now that so many choreographers (Aszure Barton, Crystal Pite and Wayne McGregor among them) have come up with their own animalistic inventions.

Still startling, though, is the venom with which Robbins treats his subject matter. He treats Stravinsky’s Concerto in G as sacrificial music for murder by feral females. Their Queen (Begona Cao) unveils a newborn Novice (Jurgita Dronina), who discovers what her body can do. Instinctively, she crushes a male intruder to death. She succumbs, however, to the next arrival, James Streeter (in a vile skimpy outfit) and mates with him, to the excitement of the swarm, waiting for prey. She refuses to kill him until she can’t help but do so – she is no warm-hearted Giselle.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Dronina, who looks too womanly as the Novice, isn’t a callous killer, which softens the brief, brutal ballet. The set, by Jean Rosenthal, is impressive: a web of ropes that tautens during the action, then slackens at the end, ready for the next victim.

William Forsythe has developed his own methods of making choreography over 40 years, sometimes surprising himself as well as his audiences. Since leaving the Frankfurt Ballet and his own Forsythe Company (in 2015), he has had commissions from many companies. For ENB, he has revived his Approximate Sonata 2016 and created a new work, Playlist (Track 1,2), his first for a British ballet company in over 20 years.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Approximate Sonata plays with the idea of unfinished business. Four couples negotiate five different pas de deux to Thom Willems’s fragmented piano score. The stage is bare, with a blue lighting gel at the back and a scrim that goes randomly up and down. The choreography is a sophisticated combination of exquisite ballet manners and sudden fierce impulses: couples break and reconvene; handholds are considerate or combative, the partnering egalitarian. Alina Cojocaru can be tough or delicate with Joseph Caley in the first and last duets, their breathing and occasional comments audible. Jurgita Dronina keeps her shoulders level in her encounter with Isaac Hernandez, who raises his, more athlete than danseur noble. Aaron Robison is elegant in his pas de deux with Precious Adams, who entwines arms with him in a contest of push-me-pull-you. It’s a game in which all the players can be themselves, knowing the rules of combat and co-operation.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Playlist is Forsythe at his friendliest, setting virtuoso ballet batterie to disco dance music. Twelve men bounce and rock, back and forth, on the beats, deploying classroom steps as fast as they can. They show off to each other, like hip-hop rivals, as well as impressing the audience. The recorded music (by Peven Everett and Lion Babe, remixed by Jax Jones) is in 4/4 time, so Forsythe organises the dancers in 4s and 2s, pacing in tendus, arms extended in formal positions, as they erupt into brisés and cabrioles.

After a mass effect first part (Track I), they break up into solos, led by Robison. He’s about the only one who insists on finding fifth position, in spite of the speed and deceptive casualness of Forsythe’s laddish reaction to the music. The ballet boyz reveal, at the end, that they sport their names on the backs of their of their see-through shirts, worn over trackie tights. Their delighted energy is so infectious that audience members leap to their feet and start to dance, after Forsythe, looking like a wild woodsman in beard and beanie cap, has taken his bows.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Altogether, a cunningly judged programme that shows off the company at its most engaging (whatever the merit of the choreography), ending with a sure-fire hit from Forsythe, having fun with American music.

You must be logged in to post a comment.