© T.M. Rives & courtesy San Francisco Dance Film Festival.

www.alexekman.com

www.tmrives.com

www.sfdancefilmfest.org

The San Francisco Dance Film Festival’s invitation to Alexander Ekman came at the perfect time. Famed for massive, boundary-pushing works like the Norwegian National Ballet’s A Swan Lake, his avant-garde Swan Lake that utlized a 6,000-litre onstage pool, the Swedish choreographer had recently completed Play, his first commission for Paris Opéra Ballet, and felt an urge to return to the small-scale, experimental work that he finds liberating and fulfilling.

SFDFF executive director Judy Flannery commissioned Ekman and his frequent filmmaking collaborator, T.M. Rives, to make a short film for this year’s festival, via its Co-Laboratory commissioning program. The longtime friends previously created Rare Birds, a documentary on the making of A Swan Lake, as well as Simkin and the City, an entertaining short film starring American Ballet Theatre’s Daniil Simkin that became a viral hit on YouTube.

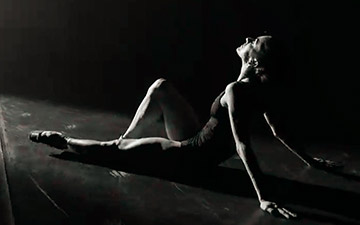

Every year the Co-Laboratory provides production support, location scouting and permitting, and a budget of about $30,000 to a handful of choreographers and filmmakers, then premieres the resulting films at the autumn festival. The creation process is fast – about one week – but artists get ample advance time to storyboard their ideas. Ekman and Rives’ packed schedules precluded planning, so their two-day shoot in the streets, alleys and parks of San Francisco was spontaneous and sometimes hilariously chaotic – props included all-purpose flour, Prosecco, dead fish and bags of popcorn – which suited them just fine. They improvised camera angles, movement, props and even some locations in collaboration with dancers Sarah Cecilia, Britt Juleen, Nathaniel Moore and Ben Needham-Wood, along with the dedicated (and incredibly flexible) SFDFF staff and crew.

© Lindsay Gauthier and Alex Irwin. (Click image for larger version)

At the end of the first shoot day, Ekman and Rives sat down to chat about their ad-hoc filmmaking experience. Our conversation quickly expanded to encompass authenticity and impermanence, ego management, the state of choreography and more than a few wisecracks. The following is an edited version.

Claudia Bauer: I had all these notes planned for our interview, but after watching today’s shoot – nothing could have prepared me for that.

T.M. Rives: You’ve absorbed our style. [laughs]

Alexander Ekman: For me this is like a totally fun project, a little bit like a research project almost. I think it’s important to do stuff like this. Because it’s scary to create when you don’t really know. I mean, it’s always scary to create, in a way. But I felt like hey, let’s have an experience. We’ll see what comes out, you know? Something will come out. It’s always when you don’t plan, you actually find new seeds. So this could also be a stepping stone to something else. The question I am asking myself in general, in my life now, is, Am I authentic? And is my movement authentic? And what is an authentic movement? As a dancer it’s kind of hard to know if you are actually moving authentically, because we are so coloured by our whole past.

CB: Why are you asking these questions?

AE: I am kind of in an interesting moment in my life. Like a big transition moment. My whole life I’ve been extremely career-driven, I just realized. My goal was, unconsciously I think, to get to the Paris Opéra to make a piece. Like, then I had ‘made it.’ And then when I finished that, I just had this huge, like, What did I do this for? Why did I do this? Is having a career important? Who am I without a career? I’m very happy that I did it, but I also came to a point where I was not so happy creating. It became more of a duty than the joy from it. I think like many creatives becoming suddenly successful, there is so much that comes with it – the expectations, and the hard work, and the pressure. Being creative is very connected to being free, I think, and not having so much expectations, you know? I’m kind of going through a big transition into something new. Like I kind of want to leave the dance scene and create something in a new way, I think.

© Lindsay Gauthier and Alex Irwin. (Click image for larger version)

CB: Do you feel like you don’t want to choreograph anymore?

AE: I think I want to create something that stays. I don’t know what it is, or how it’s gonna be done. But all these (ballets) that I’ve done, they’re sort of gone. They play for ten, eleven shows and then they’re gone, you know? And that’s how the dance world functions. The shows we have created lately, they are sort of big shows, at least some of them have become very successful. And I think they have reached a wider audience than maybe what’s the local dance audience.

CB: More of a mass audience.

AE: Yeah. And also just the amount of work that I have put in to all these shows, then to see them kind of disappear, I’m kind of like arrrrrr.

CB: That makes it a very interesting time to have this opportunity to create a film in such a low-key, experimental way.

AE: Yeah. And for me it’s totally interesting to go from the Paris Opéra to this weird, fun, small project. And I think it’s important to show yourself from high to low, and the different levels.

CB: Art-making is a different animal when you get to that high level. You start out doing your own thing, and no one has any expectations of you. And then as it grows and changes, it becomes something that’s not yours anymore, other people own it and have a piece of it.

AE: Completely. And people project so much onto you. It’s just interesting how our world sees being successful as this set thing. I guess I found that it doesn’t really change anything, you know? Well, it does in one way.

© Lindsay Gauthier and Alex Irwin. (Click image for larger version)

CB: For the worse, in one way.

AE: Totally. But I’m so happy that I have my reflective side. What do I want, and what do I want to make? I think after the Paris Opéra I got caught in a sort of ego – I felt my ego kind of going in a really unhappy (direction). And then I went to meditate a lot on my work, a lot on myself, and came back to more, like, love and compassion. And I realized that’s actually what I can do with this position that I have worked myself to, is give back and give nice experiences to people. When you take yourself out of the equation, it’s kind of nice, actually. Like, it’s not really about me, it’s about creating for others, for us. But I also love impermanence. If you hold on to something or attach to something, you’re just gonna get misery, actually.

CB: So you’re making this film, but you don’t know the city, you didn’t know the dancers, you didn’t know anything. Which is risky but it can be incredibly exhilarating – it’s really total freedom.

AE: I think you’ve just got to dare to go there. It’s hard, it’s scary, but creation is always kind of scary in one way or the other. So I think you’ve just gotta have guts and go for it anyway. There’s pressure for me, there’s pressure for us [as a filmmaking team], there’s pressure coming up with an interesting theme. And for me, there was pressure to actually improvise and dance in front of everyone also. Because that’s not easy.

CB: It’s so interesting that you say that, because watching you, one would never guess that you had that fear. Maybe because you’re very practiced at performing, you know how to put that out of your mind in some way.

AE: I guess it’s not a huge fear. But if you’re gonna create at all you’ve just gotta step over that and see that it’s there. Otherwise no one would create, I guess. I try to also remember that some will be great, some will be – we’re shooting a lot of material. It’s easy to forget that when you’re in it. You’re like, Oh that’s not good, that’s not good. But it’s kind of my job to see the problems. And I realize that the dancers, they only hear me going, ‘Do it a bit more like that or more like that.’ That’s kind of annoying, actually!

© Lindsay Gauthier and Alex Irwin. (Click image for larger version)

CB: Talking about the transitional period you say you are in, do you feel like being the authority figure gets in the way of being an in-the-work artist?

AE: I think my challenge is to try to remain equal. ’Cause when you you’re the boss like that, to still connect with the dancers can be hard. I think that’s what I’m learning slowly. How to deal with that. For me, when I take myself out of it, and I think that I am doing this for someone else, then I can work with it. Then it feels like it comes from a nice place, instead of an ego perspective. ‘This is my piece, this is my career.’ Then I don’t like where that comes from, and I don’t like myself.

CB: How do the two of you work together when you’re making a film?

TMR: I worry more about technical stuff than he does, and it can be annoying because he’s trying to get to the next image. But I’m thinking about my task in the editing chair. I’m thinking about continuity.

AE: I think what we have both is a sense of humor. We have a similar humor somehow. We don’t know what’s going to happen, so you need to be flexible. The second you hold on to something, you’re gonna be upset. That mindset in a creation, it’s so valuable to be flexible, to not hold on to anything, really.

CB: The SFDFF team doesn’t have any expectations of the outcome, but they seem to have every faith that it’s going to be something worth looking at.

TMR: It won’t be a clichéd thing. [laughter]

AE: I wouldn’t do anything if it was that. I mean, there is no need for another pretty dance work. If we don’t get surprised, if we don’t get captivated – I want to feel something. I don’t care how, but if I don’t feel anything, there is really no need for art.

© Lindsay Gauthier and Alex Irwin. (Click image for larger version)

CB: You’ve shot hours of footage. How are you going to edit it down to 5-8 minutes?

TMR: I don’t know. It’s gonna be – the material will decide. Maybe three minutes of black at the end.

AE: Or maybe at the beginning.

TMR: That’s why you’re the genius. [laughter]

CB: Pretty much everything you shot for the film was improvised.

TMR: It’s an interesting extra layer. Because if you improvise, you’re juggling chaos around.

AE: You turn your mind off, the critical thinking, the awareness. When you improvise, the more you can visualize, the more you can play. When you direct dancers, if you find the key word – when I work with thirty people in front of me, if you find something that everyone can picture, they all start doing the same thing. Because there’s a human understanding. And sometimes the less words you say, and the more direct it is, it will make everyone understand.

CB: Alex, you saw San Francisco Ballet’s Unbound Program D [with works by Edwaard Liang, Dwight Rhoden and Arthur Pita]. I loved [Pita’s Björk Ballet] because it messes with the audience’s expectations.

AE: I love it for that. It’s interesting, the context. If (Helgi Tomasson) would have put Arthur Pita’s piece first (on that bill), the audience would have been like, what the hell is this? But since it came after those two pieces, it was also very obvious how it works to entertain the audience, because something different happens. Like some of my pieces, I show the same piece – sometimes in the beginning, it’s just a little bit too weird for the audience. If they’ve seen a couple of ‘dance’ pieces (first), then they really love it because it’s just fun.

TMR: In spoken word, there’s a phenomenon called ‘score creep.’ They’ll do a round of three people and have an applause meter. It’s known among those who perform that the last one has an unfair advantage, because people’s approval tends to ramp up. They give more love to the last one.

© and courtesy San Francisco Dance Film Festival.

CB: Some of the Unbound Festival works I’ve liked, and some not.

AE: That’s the point – to push them to be fucking daring, to be weird. Why not? I think what you want in a theater in any city is to make people talk. You want the buzz. Whenever we do this safe kind of stuff, it’s fine, and people find that nice too. Not everyone wants different. We can have both. One thing doesn’t erase the other.

CB: It goes back to what you were talking about earlier, the transition point that you’re in. You have to try to decide which way to go.

AE: I’m kind of addicted to that thing of, What is this? If I don’t feel that, I don’t get excited.

CB: Do you feel like you can still do that kind of work, find that feeling, on the trajectory your career is on?

AE: Well…yeah. Like doing projects like this, because it takes it down to an experimental level again. I have to be okay with fucking up, to be okay with, maybe this is not going to be the most exciting, best dance film ever, you know? Because ‘I am Ekman wow wow wow.’

CB: With a capital E.

AE: It’s true! [laughs] I would rather be different but daring, than safe. I would rather be that guy that did something terrible, than safe.

CB: Does it mean enough to you to forgo the other, more ‘successful’ path, or do you think that you can balance both?

AE: Oh yeah. The most unexpected thing I could do is do a really boring ballet.

TMR: Everyone in low-cut leotards.

AE: That would be interesting. That would cause talk!

TMR: Alexander Ekman, surprising again, by being boring. [laughter]

AE: To me, it’s all about setting ourselves free.

The 9th annual San Francisco Dance Film Festival runs 4–14 October 2018. Sincere thanks to Judy Flannery, Co-Laboratory producer Lindsay Gauthier and the SFDFF staff for making this interview possible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.