© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

All Robbins No. 1 – Bernstein Collaborations: Fancy Free, Dybbuk, West Side Story Suite

★★★✰✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

8 May 2018

www.nycballet.com

davidhkochtheater.com

Bromance

I had my first glimpse of New York City Ballet’s Jerome Robbins centennial retrospective on the evening May 8. The program celebrated one of the most fruitful collaborations in music and dance, that between Robbins and the composer Leonard Bernstein. The ballets on this program, Fancy Free, West Side Story Suite, and Dybbuk, span three decades, from 1944 (for Fancy Free) to 1974 (for Dybbuk). All three scores were played with great flair by the New York City Ballet Orchestra, under the baton of its musical director, Andrew Litton. Litton has a way with jazz – both Fancy Free and West Side Story really swung.

Fancy Free was Robbins’ very first ballet, made when he was just 26 and a dancer at Ballet Theatre (later American Ballet Theatre), before he decamped for Balanchine’s company. It is one of those works one never tires of seeing, even if it is an artifact of another time, almost of another world. Its most winning quality is its innocence, an innocence that doesn’t preclude sexiness. The setting is World War II, when the country was teeming with young men going off to war. There’s no question about what these three sailors on shore leave are looking for, but somehow their randyness never comes across as threatening or lewd, even when they take a young woman’s purse and toss it around in order to keep her with them a while longer. Then there is the second encounter, in the bar. The moment in which the rather more sophisticated woman in pink, initially bored, begins to take an interest in the young sailor never fails to bring a lump to one’s throat. Their duet is sexy, exploratory. She decides to take a chance on this kid, despite his clumsy freshness. The subtext is that he could be dead tomorrow.

The cast here was almost completely new. The sailors – Harrison Coll, Roman Mejia, and Sebastian Villarini-Velez – are all in the corps, and Mejia joined less than a year ago. Alexa Maxwell, as the girl in yellow, was also new. The only veteran onstage was Tiler Peck, quietly sultry and sculptural as the girl in pink. As one might expect, the cast still needs to grow into the ballet and find more personal touches in the characters – and to relax a bit – but things are off to a promising start. All three are charmers and Villarini-Velez was particularly musical in the Latin-flavored rumba, inserting piquant pauses between the phrases. Coll’s dancing is winning and open-hearted; Mejia combines precision with a relaxed, grounded stage presence.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

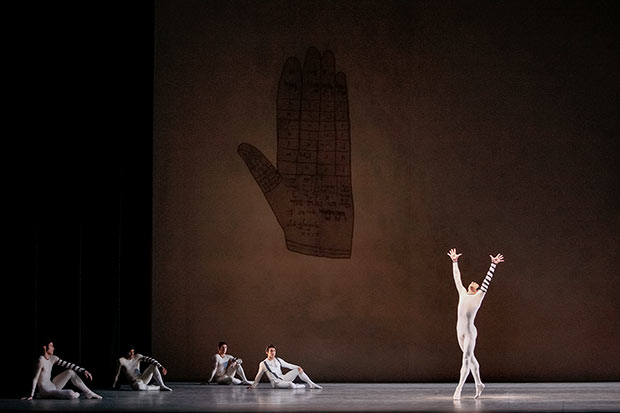

Like the evening’s closer, West Side Story, Fancy Free is frequently performed. But the middle ballet, Dybbuk, hasn’t been seen since the company’s previous Robbins festival, a decade ago. The music, which draws on the numerology of the Kabbalah for its harmonies and rhythms, is at times dissonant and spiky, at others operatic, and at times almost klezmer-like. The story is inspired by S. Ansky’s play about a spirit – a dybbuk, a figure from Jewish Central-European folklore – that enters the body of a young woman (Leah) who loves one man but is promised to another. As two male singers (Conor McDonald and Joseph Beutel) cry out “Leah!” and “Adonai!”, a man jumps and twists in the air, transforming himself into something inhuman before our eyes.

The most effective parts of the ballet are the opening and the end – two ensemble dances for a group of seven men, dressed in black. Oddly, they are reminiscent of the four men at the beginning of Balanchine’s Agon. As in Fiddler on the Roof, Robbins has reinvented the Jewish line dance, turning it into something almost abstract, a series of interlocked shapes and shadows, bending, twisting, unfolding in different directions. The patterns are dazzling; it’s impressive, also, to see how advanced Robbins was in the art of male-on-male partnering. Here, men lift, support, and counterbalance each other with ease. Later in the ballet, they create a formation that looks like a sunburst. In contrast, the male-female pas de deux – danced by Anthony Huxley and Sterling Hyltin–is less about partnering than about mirroring and symmetry. Huxley and Hyltin’s steps are often the same; they rock side to side, or glide like sleep-walkers across the stage. It’s only after Hyltin has been possessed by Huxley’s spirit that their bodies merge into one.

Dybbuk is an odd, and often interesting ballet, though it doesn’t quite manage to maintain its intensity from beginning to end. The opening line dance is mysterious and thrilling. The man’s thrashing solo is convincingly wild. But the language Robbins uses for the lovers – the gliding and rocking and sleepwalking – feels thin, and not quite up to the task of depicting the strangeness of what is happening. A long passage in the middle of the ballet, a series of male solos, adds little to the development of the story or its visual themes. It’s only at the end, when the woman begins to echo the man’s crazed movements, and when the lovers reunite, that the ballet snaps back into focus, leaving a haunting impression.

The casting, too, was not ideal. Huxley, a beautiful dancer, is too neat, too careful for the role; he doesn’t lose himself or transmit the hauntedness of his character. Hyltin is more dramatic, but lacks weight. When they dance side by side, she and Huxley look like two peas from the same pod, not forces inexorably drawn toward each other. In order to cast a spell, the ballet requires performances of greater intensity.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

There were signs too that perhaps the ballet hadn’t gotten quite the number of rehearsals it needed; perhaps it’s unavoidable in a season as packed as this one, and in a company that still has not settled on a new artistic leadership. West Side Story Suite is a more forgiving ballet, and one in which the dancers clearly feel comfortable. The good news is that the two dancers débuting in the singing roles in “America” (Indiana Woodward and Meaghan Dutton-O’Hara) have fine voices. The tenor (a guest) who sang Tony’s aria, Jonathan Riesen, was also in excellent voice. And the band wailed. But West Side Story, unlike Fancy Free, is showing signs of age. After the destruction wrought by Hurricane Irma, it’s uncomfortable to listen to lyrics like “I’ll bring a TV to San Juan…If there’s current to turn on” and “everyone there will have moved here.” In fact, the whole song, with its jabs at Puerto Rico’s backwardness, hits a sour note. The Sharks now read as caricatures from another time. (And why must all the Sharks be dark-haired?) There’s no doubt that West Side Story is a classic, and that its movement language feels as vital as ever – and is still influencing young choreographers working today – but more and more, it is beginning to look and feel its age.

One of Robbins’ great talents was sniffing out the style of his time, but this inevitably places a date stamp on his work. It is what’s missing in Dybbuk, in which he tried, not completely successfully, to create an atmosphere outside of time. In Fancy Free, the style became timeless; in West Side Story, it created a time capsule.

You must be logged in to post a comment.