© Graham Watts. (Click image for larger version)

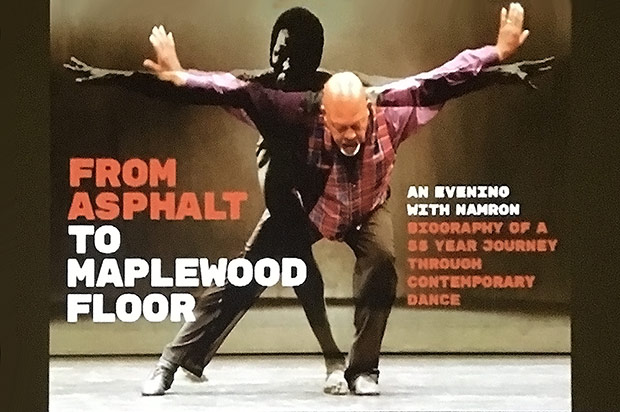

An Evening with Namron

From Asphalt to Maple Wood

London, The Place

29 May 2018

www.namrondance.com

Sub-titled, From Asphalt to Maple Wood, ie from the streets of Jamaica to the wooden dance floors of London, this evening with one of the legendary founding figures of British contemporary dance could more easily have been referenced as From Mandeville to Buckingham Palace (a title, Namron confesses to have preferred but was persuaded against).

It’s been quite a journey for the first black dancer to have been employed in a British dance company: beginning in the Jamaican town of Mandeville (oddly, for anyone brought up in England, Mandeville is in the parish of Manchester, in the county of Middlesex), where he lived with grandparents; and then, in 1958, via a BOAC aeroplane, hopping from Kingston to Gander, in Newfoundland, and then onto Shannon, in Ireland, and finally Heathrow, where the thirteen-year-old boarded a bus to be met by his mother at Victoria Station. School – where he was Head Boy – led to an unfinished engineering apprenticeship, interrupted by a desire to dance; and a career that led to Buckingham Palace, in 2014; appointed an Officer of the British Empire for his services to dance.

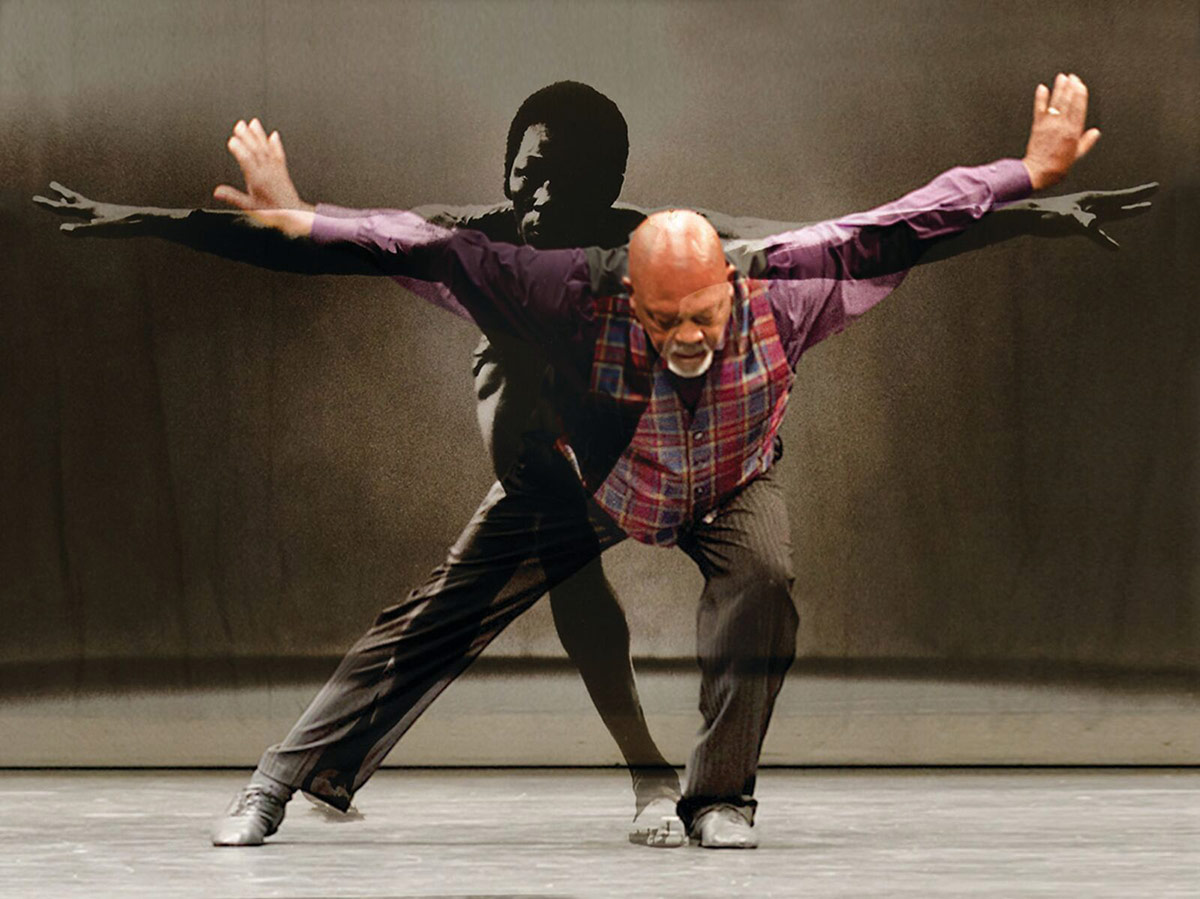

For around 80 minutes, Namron entertained his audience, largely comprising past and present luminaries of London contemporary dance, with stories and reminiscences, often breaking into movement, before finishing with a brief question & answer session, compered by Kenneth Tharp, formerly CEO of The Place, on the evening of his first day as Director of The Africa Centre. Now in his early 70s, Namron moves with the steely grace of a man who has never stopped dancing; still teaching, as he approaches his 60th year, in dance.

© Graham Watts. (Click image for larger version)

It all started, for Norman Murray, as an engineering apprentice, in Kilburn, where a fellow-worker, named Tommy, introduced him to the Willesden Jazz Ballet Group, down the road, in Cricklewood. His parents thought he was playing cricket and it took awhile for young Norman to blend in to the group, but he persevered, and loved it. By then, it was 1962, Norman was 17, and his teacher, Alison Beckett, was his elder by just one day. They have been collaborators, ever since, including at Northern Contemporary Dance School, where they can both be seen in a Granada TV documentary, filmed in April, 1989. A charming, recent film of the pair chatting in an office was shown as part of the performance.

In a press cutting for an early show by the Willesden Group, Norman is revealed as the only man amongst a clutch of 45 women, including Leonie Urdang (who would go on to establish the Urdang Academy). His mother came to see that show but was unimpressed about her son’s keenness to dance, steadfastly refusing to sign the papers that were needed for him to take up a scholarship at the Rambert School, in 1965. It was “all-out war” remembered Namron, humorously imitating his mother’s indignation (“Don’t Test me, you fool”). Eventually, his equally-reticent father gave way and interceded, successfully, on his behalf. Namron proudly relates to his teaching by Madame Rambert, herself, in the famed venue of Notting Hill’s Mercury Theatre, also reporting that Christopher Bruce was a third year when he joined the school.

Namron’s early experiences of seeing dance included the Martha Graham Company and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. As a student, he went to the latter’s opening performance, in London – all he could afford – and was desperate to see more of the season. And, he did. He saw every show by pretending to be an Ailey dancer who was “off” for that night! The Ailey Dancers were a “revelation”, he said (I wonder how many times that quip has been made).

Martha Graham’s dancers had a similar impact and when they taught part-time classes at the newly-formed London Contemporary Dance Trust, Norman was one of the first to enrol. When the London Contemporary Dance School opened, a year later, in 1966, he taught the new students. In 1969, he became a founder member of London Contemporary Dance Theatre, where he remained a leading dancer for the next 18 years.

So, why, when and how did Namron come about? Unfortunately, his name change happened as a result of the everyday racism that Norman encountered. He was offered a tenancy in a new apartment, as Norman Murray, sight unseen, but on arriving to take up residence, suddenly the room was no longer available. On his way back to his digs, in Baker Street, Norman spotted the name plate of a Solicitor and Commissioner of Oaths with the subtext of changing names by deed poll. It cost 10 shillings and sixpence (52 and a half pence in today’s money) and he decided that Norman Murray should turn into Namron Yarrum. Next day, at The Place, he told Bob Cohan and Robin Howard and they said the new name was too much of a mouthful, so Namron, he became.

Later, he tells a story about Howard (the founder of The Place and all that went in it); the grandson of a Prime Minister (Stanley Baldwin) whose philanthropy did so much for dance. Howard had lost the use of both legs, the result of a wartime injury, and Namron recounted – with great expressiveness – the nightmare of being a passenger, in Howard’s car, in a manic race to London. An experience to be endured, only the once!

© Anthony Crickmay & Andrew Laing. (Click image for larger version)

Namron recounts his experiences of racism without a hint of bitterness, almost dismissively referring to the common sight of signs in pub windows – “No blacks, no Irish, no dogs”. He is clearly – and rightfully proud – of breaking the stereotypes in British dance; of becoming an inspiration to generations of black dancers who have followed, enlarging the envelope of BAME dance in Britain. It was both humbling and refreshing to feel the love and respect from younger black dancers, now making their mark as future leaders of British contemporary dance, such as Mbulelo Ndabeni and Freddie Opuku Addaie, both of whom paid tribute to the significant inspiration they had derived from Namron’s career and teaching.

Namron kept us entertained throughout with his natural ability as a story-teller, despite self-deprecating references to the fact that dancers don’t usually talk, on stage. His, chuckling, raspy voice needed lubrication from a carton of Ribena, from time-to-time, and he made a few offstage exits (while the audience was occupied with film and photos) to change, sporting a variety of waistcoats but never without his hat.

The trajectory of his career was unevenly spread with much reminiscing on the early days; the 18 years at LCDT whistled through, with a few references to performing Cohan’s work and to Namron’s legacy in Robert North’s Troy Games, which he staged for Dance Theatre of Harlem, in 1977, and to his own seminal work, The Bronze, which entered the LCDT repertoire, in 1975. His role as a founder teacher at the Northern School of Contemporary Dance – where he was on the staff for fifteen years – and at Phoenix Dance Theatre were mentioned only in passing and there was little or nothing about his work, since the millennium.

It seems clear that these gaps were largely to do with an absence of visual material from those years, which is a pity (especially if it is lost) but Namron’s humour and his ability to fill the stage with an engaging presence made up for the lack of film clips from his remarkable career. It’s hard to distinguish the boundary between Namron’s self-direction and the influence of Tamara McLorg as the credited director but it is surprising that the technical team didn’t pick up on the smattering of spelling mistakes in the projected captions; although, in one important sense, these incongruities added to the evening’s unassuming simplicity.

Once upon a time, television regularly brought a cheesy “An evening with….” one celebrity, or another, with an all-star audience. The parallel was there in terms of the “great and the good” of the contemporary dance world spending an evening listening to one of their own, but all other similarities ended since this was an entirely unpretentious and uplifting show. It was a great pleasure to learn more about this inspirational man. Truly, a game-changer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.