© Agathe Poupeney / OnP. (Click image for larger version)

Paris Opera Ballet

Thierrée / Shechter / Pérez / Pite: Frôlons, The Art of Not Looking Back, The Male Dancer, The Seasons’ Canon

★★★★✰

Paris, Palais Garnier

30 May 2018

www.operadeparis.fr

It is May 30 and the Palais Garnier is showcasing four contemporary choreographers and their inspirational creations for the Paris Opera Ballet (POB).

The evening opens with the Swiss choreographer James Thierrée’s Frôlons. Surprisingly, the performance begins in the grand entrance hall and on the staircase of the Palais Garnier opera house. The spectators, who are not permitted to take their seats in the theatre, observe the dancers with wonder, shock or even irritation. I feel the thrill of a performance that is shattering convention.

Eerie masked dancers in metallic gold costumes decorated with black fabric and green tassels become two-legged creatures. Their acrobatics emulate the circus, which has inspired Thierrée’s vernacular. The choreography is both geometrical and languid. The dancers perform solos with angular gestures and poses. Joining one another, they then forge swirling couples. The sharpness of their movements crumbles as they snake around their partners’ bodies. Golden metallic dragon-like beasts accompany the dancers. They shake their long tails into the audience. Bewildered and even frightened by the four-legged dancing monsters, the spectators step back to avoid them. The audience and the building are as much a part of Thierée’s choreography as the dancers.

© Agathe Poupeney / OnP. (Click image for larger version)

Thierrée’s piece is a mise en abyme. It is a freakish reflection of the Palais Garnier and its jumbling of spectators, décor and architecture. The dancers repeatedly walk up and down the grand staircase. They mimic the spectators who continue to enter the theatre. Their gold and tasseled costumes mirror the opulent décor of the surroundings. Miniature chandeliers adorn the heads of the metallic beasts. The cluster of opaque lights on the top of the head of a dancing creature copies those perched on black pillars encircling the Garnier’s interior. Yet this mirroring is monstrous. Thierrée’s demons and dragons show us another side to its luxuriousness. With its abundance of gold and excessive splendour, the theatre borders on the gaudy, grotesque and even horrific.

When the dancers eventually move to the auditorium, the performance is less successful with the audience waiting a considerable time before the stage dancing begins. This break destroys its momentum. Frôlons is captivating when it takes place in the grand hallway and on the staircase of the theatre.

Next up is the Israeli choreographer Hofesh Shechter’s new version of The Art of Not Looking Back, originally created in 2009. Beginning with primal screams, this twisted homage to his mother solemnly responds to her leaving him when he was two. Nine magnificent women dancers perform in this collage of movement, bodily sounds, voiceovers, lighting and sound tracks. Together they weave a poignant visual and sonic tapestry of emotional pain.

© Agathe Poupeney / OnP. (Click image for larger version)

The autobiographical voiceovers on the soundtrack shape the choreography.

“She tries to be everything to me because she is nothing to me.”

“There is no content – it’s like having a bucket with a hole. No matter what you pour in, it’s always empty.”

The polarities of this anguish – both all-encompassing and insignificant – are embodied by the dancers. Their fluid and ordered moves attempt to make sense of the chaos and emptiness of the choreographer’s pain. Impulsive and erratic gestures are never calmed down. This tension is enacted throughout. At one point, the dancers repeatedly assume an almost completed ballet fourth position to Bach’s Concerto for two violins in D minor. They continuously break from this collected pose with fractured, sharp and disjointed moves. These movements are executed with exquisite precision to blasting techno. Facing the audience, the dancers in another instance move their bodies ever so slightly to an enormous wave of rhythmic music. This seemingly inconsequential yet powerful gesture bears the immensity of deep pain.

Beautiful, dark and at times repulsive, this exploration of difficult emotion stems from Schecter’s infancy. The sounds of vomit and gagging, screams and blasting rhythmic music could be disturbing – spectators are handed earplugs before the performance. This noisy, unpredictable and self-indulgent piece may not be for everyone. But the pain of loss, so viscerally enacted in this autobiographical work, touches us all. And that, I feel, is the point of this pessimistic yet deeply personal and vibrant work. The soundtrack of Shechter’s voice at the end The Art of Not Looking Back draws the audience into his world.

“We should – ladies and gentlemen – not speak of this.”

© Agathe Poupeney / OnP. (Click image for larger version)

The Male Dancer, by the Spanish choreographer Iván Pérez, is new for this bill – like the earlier Frôlons. Ten male dancers appear on stage, each wearing a gaudy getup designed by Alejandro Gomez Palomo. The costumes become characters in Perez’s choreographic exploration of masculine identity. Lilac silk pyjamas. An ornate billowing robe that evokes the dress of past emperors and kings. Shimmering wide-legged disco pantsuits. Tan and grey tunic outfits that recall the dress of Ancient Greece and Rome. These costumes are storytellers. They recount how styles of dress that verge on the feminine have been acceptable as male attire in different times and places. The dancers give life to these colourful and extravagant costumes and their tales of masculinity.

Aspects of the choreography suggest that the male dancers cannot transgress the chains of stereotypes. This constraint emerges through poses that begin but are not followed through. At one point in the choreography, the dancers raise their arms in the ballet fifth position. Yet this position is never completed. Instead their arms collapse to touch their chests as if trapped by their bodies. The dancers in another moment seem to break out of the traditional roles of masculine and feminine. In a pas de deux that resembles a Greco-Roman wrestling match, each dancer alternates between collapsing into his partner or supporting him. A solo performance near the end by a dancer in an extravagant yellow bathrobe trimmed with faux fur conveys this struggle to break free from the constraints of masculinity. The robe becomes a carapace – a shell of shimmering “feminine” fabric – that covers the dancer. His muscular and almost naked body continuously slips out from under the flowing material to reveal his physical vitality and force.

The melancholic and spiritual music of Arvo Pärt’s Stabat Mater seeps into the choreography. It evokes the sadness of a masculinity that is stuck in an iconic representation and almost religious in its fixity. But the music also stirs a longing for its liberation.

The Male Dancer is less emotionally charged and engaging than the first two pieces. The rhythmic pattern of the choreography, which moves between fluidity and its eventual disruption, lulls me into a state of calm. Perhaps this tranquility is essential to make the audience think of the question of male identity. Pérez’s work is a wonderful choreographic study of how masculinity needs to be re-thought and re-expressed in dance and in everyday life beyond the stage.

The evening closes with the Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite’s The Seasons’ Canon, which was created for the POB in 2016. I am overwhelmed by the movements of the dancers, which are exquisite in their perfect dialogue with Max Richter’s recomposed rendition of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. Crystal Pite’s poetic choreography compels the audience to respond physically and emotionally. Dance expresses the unspeakable.

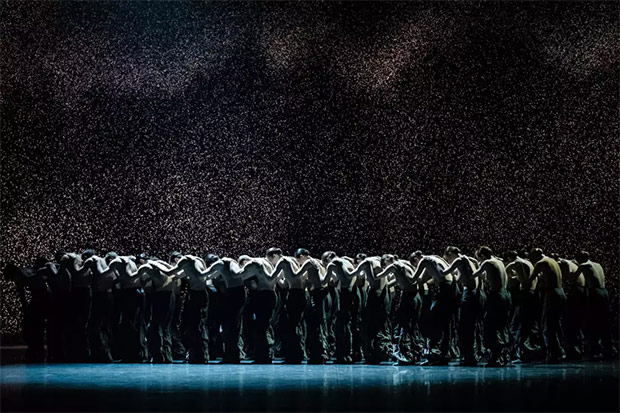

With green paint extending down their throats, fifty-four dancers are dressed identically in baggy combat trousers and sheer nude tops. Together they embody the force and complexity of nature.

© Agathe Poupeney / OnP. (Click image for larger version)

They dancers forge a giant wave at the beginning of the piece. Their synchronicity is outstanding. At one point an individual dancer rises up from the massive collective and moves her head to catch the notes in impeccable unison with the music. She is a drop of water in the sea. This gesture is breathtaking in its simple power. This directing of the viewer’s eye to singular highly charged gestures is repeated throughout.

Later the mass breaks apart and each dancer begins to move separately. They fall from one another to create an exquisitely intricate and ornate living tableau. It brings to mind how human figures are staged in nineteenth-century romantic paintings – Theodor Gericault’s The Raft of Medusa or Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy’s Ossian Receiving the Ghosts of the French Heroes.

Running through the core of Pite’s artistry is struggle. The movement vernacular enacts this tension. Dancers move parts of their body in opposition. Knees bent in second position, they are repeatedly forced to shift from left to right while the head and shoulder are overextended to the back. Such oppositions are enacted throughout. They draw the audience into the performance. We feel a disturbance that matches the escalation of emotion as The Four Season’s moves between sensations of striving and overcoming. In turn, Pite’s choreography enacts the turmoil and transcendence within the natural world.

Crystal Pite’s work stands out as the crowd-pleaser. With huge cheers and applause, we rise to our feet for the dancers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.