© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Whipped Cream

★★★★✰

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

5, 6 (mat) July 2018

www.abt.org

More is More

The close of New York’s ballet season is upon us, and American Ballet Theatre is finishing things off with a sugar high in the form of Alexei Ratmansky’s confectionary-themed Whipped Cream, from last year. It’s a big ballet, with a huge cast, including no less than ten leading and secondary roles. Like the Petipa ballets that Ratmansky has been delving into with increasing frequency, it is all about creating a world onstage. The sets and costumes, by the West Coast neo-baroque pop surrealist Mark Ryden – there’s no other way to describe him – are as important as the lush, rococo 1922 score by Richard Strauss and the choreography by Ratmansky. It’s ballet as spectacle, or féerie, as they called this sort of thing in the nineteenth century. Think Sleeping Beauty, but with strawberry-parfait ladies and marzipan soldiers in the place of fairies and storybook characters.

Ratmansky hasn’t sacrificed sophistication, however; there is plenty here for the demanding dance lover to enjoy: stylistic jokes, references to other ballets, especially Sleeping Beauty, complex group dances, as well as intricate, detailed and devilishly hard solos for everyone involved.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The good news is that the production has settled, and now breathes in a way it didn’t last year, when all the puzzle pieces had yet to find their place. The dancers appear less taxed, and as a consequence, everything looks easier, clearer, and funnier. The story is just a skeleton, really: a boy eats too much whipped cream on his communion day and ends up at the hospital, from whence he is sprung by a princess from a magic, candied realm and her facilitators, a trio of liqueurs. (The liquors cajole the doctor and nurses into drinking, and the boy gets away.) He ends up in a magical kingdom where he can eat whipped cream to his heart’s content, surrounded by fantastical beasts and warm, happy people. It’s the ultimate in wish fulfillment.

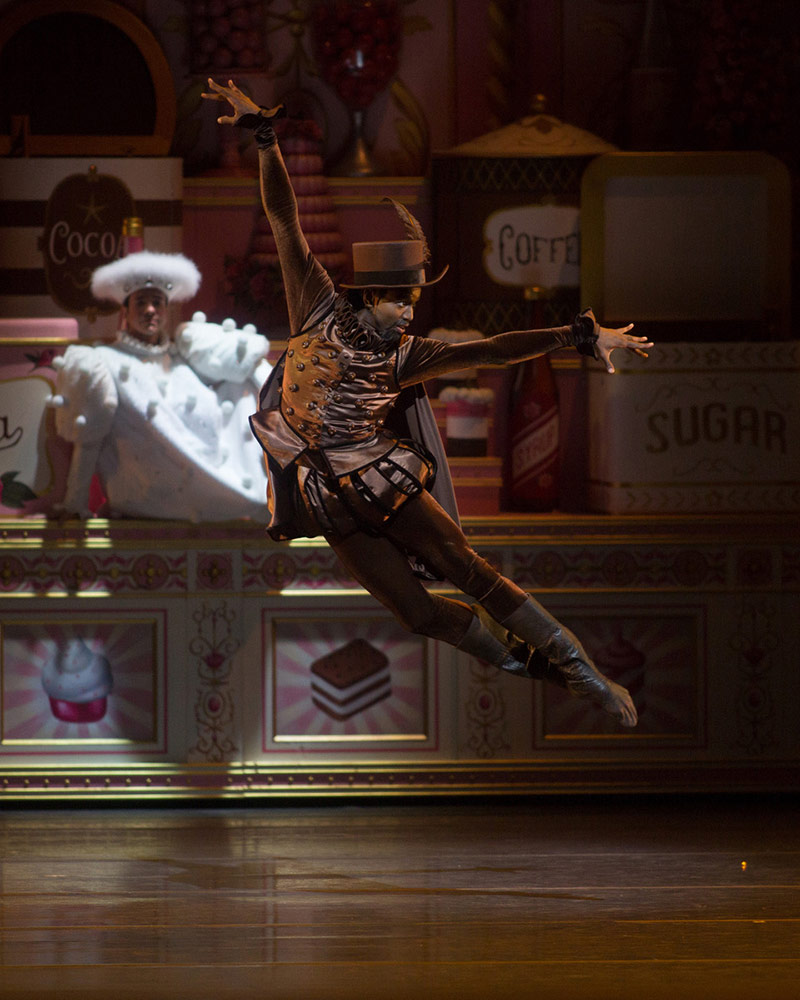

What matters, though, is what happens along the way, the unspooling of fantastical character dances only tangentially related to the main plot. Ratmansky gives us layer upon layer of fantasy: In the first scene, after the kids have been trundled off, the sweets come out of the cupboards to dance. First, there is a pitched battle between various armies of confections: marzipan archers, spear-wielding sugarplum soldiers in pink pantaloons, gingerbread men clutching clubs. Then, once the field has cleared, the royalty comes out to play: Princess Tea Flower and her four attendants; Prince Coffee and three pals; and later, two additional suitors for Tea Flower’s attentions. (They pop out of giant tins at the pastry shop.) The second act, which begins in an Expressionist hospital room, complete with a giant lamp and stinky bedpan, introduces a battalion of sinister nurses carrying giant hypodermic needles, and a doctor with a giant head. The enormous heads worn by various “real,” adult characters, including the priest, doctor, and carriage driver, are works of art, with eerily human expressions.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

With greater clarity, it is possible to really see the intricate choreography, dripping with ideas and style. Tea Flower is an art-nouveau beauty, with floppy wrists and a soft, sensual coordination, à la Fokine. In turns, her head tilts to the side, arms limply framing her upper body, leg held low. Cocoa is as preening as Rudolph Valentino. He enters by swooning down from a shelf, confident that his men will catch him before he hits the floor. The pas de deux that follows unspools in endless variations to a drippy violin melody featuring no fewer that three climaxes and false resolutions. (Bravo to the violinist here.) Tea Blossom is swooped up into the air and brought back safely to nestle in Cocoa’s arms; later, he crawls at her feet, and she bows to him with an elaborate flourish.

In Act II, the boy, cowering in his hospital bed, will meet another princess, Princess Praline, more appropriate in age and affect. Praline is a saucy teenager, Tea Flower a a femme fatale. Praline arrives atop a giant white beast (a “snow yak,” according to the program), accompanied by a fantastical menagerie: a tall “long neck piggy” who, it must be said, looks more like a giraffe, with floppy ears; a woman covered in gumballs, a snake (a man lying on a skateboard, with an enormous tail), and an adorable pink teddy bear (also identified in the program as a yak). They dance along as the princess introduces herself in mime. Then she invites the boy to dance – their youthful, charming pas de deux is accompanied by a waltz that would not be out of place in Strauss’s Rosenkavalier.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The nightmare of the hospital room – complete with Ryden’s giant blinking eyes and grotesque anatomical drawings – meets the confectionary fantasy of the candy shop. The dancing in this scene is wonderfully companionable. Praline teaches the boy how to dance and encourages him; as his confidence grows, they dance side by side, pushing each other to greater heights. In the end, it is she, not he, who steals a kiss.

The ballet still has a few flaws – the whipped-cream waltz that completes the first act isn’t equal to the sweep in the music, and struggles to fill the stage; some sections are too long, some too short – but these shortcomings don’t mar the overall effect. The audience laughs, the company looks great, the orchestra, for once, sounds full and vibrant, and you leave the theatre with a rare feeling of joy. Lightness of spirit and complexity of execution in one delightful package.

I caught two casts, both of which included role débuts. As the boy, Arron Scott may lack the requisite overlay of technical brilliance, but he was the most human, and the most touching of the dancers I’ve seen in this role so far. I saw Gabe Stone Shayers’ second performance of the boy (he had débuted 2 days earlier) and found his dancing extraordinarily musical, with crystal clear footwork and a great jump. Unfortunately, in the final scene on July 6 he hurt himself descending from a leap and had to mark the final bars of music. Hopefully it was nothing serious.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Calvin Royal III cut a fine figure as Prince Coffee, but hasn’t yet found his take on this deliciously tongue-in-cheek character, unlike James Whiteside, who imposes himself on the role like a panther on the prowl. (The music is reminiscent of the tango, accompanied by swooping violins and castanets.) Isabella Boylston is equally at home in the coy, rococo flourishes of Princess Tea Flower, which Devon Teuscher dances with a greater sense of silent-screen drama. Both approaches work. Both Cassandra Trenary and Skylar Brandt were crisp, fun, and sparkling in the staccato, Russian-folk-tinged choreography for Princess Praline. Brandt was, if anything, a touch sweeter, with a thousand-watt smile. Joseph Gorak’s fastidiousness found a perfect outlet in the elegant choreography for Prince Cocoa. I could go on, but I’ll mention just one more: Catherine Hurlin, a born comedienne, ideally suited to the vaudevillian role of Mademoiselle Marianne Chartreuse. Her loopy performance in here is enough to justify her recent promotion to soloist.

In short, ABT seems to have a winner on its hands, a popular ballet that takes advantage of the cavernous Met stage and orchestra pit and uses the company’s resources to the fullest. Sometimes, more is more.

Terrific review – we saw the second Gabe Stone Shayer performance too – he is so beguiling!! When will this excellent dancer be promoted???

Thank you, Beverly! And, good question! I was very surprised it didn’t happen this season.