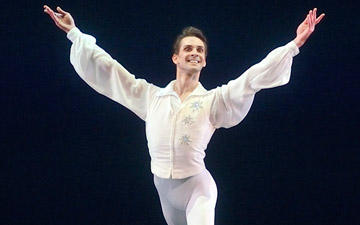

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

17 Oct: 2018 Fall Gala – Le Jeune, Dream within a Dream (deferred), In the Upper Room

18 Oct: Symphonie Concertante, Dream within a Dream (deferred), Fancy Free

19 Oct: Songs of Bukovina, Garden Blue, In the Upper Room

★★★✰✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

17,18, 19 October 2018

www.abt.org

davidhkochtheater.com

ABT Fall Season Notebook

American Ballet Theatre’s fall season just began on Wednesday, and yet it’s practically at its halfway point already. The fall season is too brief, particularly because it always feels as though it takes the company a few days to warm itself up. The dancing at the gala on Oct. 17 was a little slapdash, but by Friday things had begun to settle.

The gala was heavy with speeches; there were honorees to thank, and a new initiative to tout. Most of the talk was about the “Women’s Movement,” the company’s new commitment to commissioning work by women choreographers. (All the speakers were women, too.) Appropriately enough, the gala program consisted of three ballets by women. I’m not sure how I feel about packaging women’s work in this way, branded with a label and programmed together like a one-time special event. But if it helps open up the ballet world to new voices that would otherwise go under the radar, it’s surly to complain. The rewards will be seen down the line.

The big premiere of the evening was Michelle Dorrance’s Dream within a Dream (deferred). It was a rare misfire for this inventive tap choreographer, usually so adept at whipping up clever and unexpected combinations. A few months ago she made an effective teaser for the company’s spring gala. Dream contained many of the same elements: dancers sliding or striking the stage with their pointe shoes and or clapping out rhythms. But this time Dorrance tried to expand these sound-making experiments into a larger structure, something along the lines of a jukebox ballet. There was lindy-hopping and tapping, and, out of nowhere, a melancholy solo for a male dancer – Calvin Royal III, looking soulful as always, but underused.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

None of it really worked, despite fantastic music by Duke Ellington, played by a sweet jazz band, ABT’s orchestra augmented by 5 sax players, a trumpeter, a bass, a jazz pianist and a drummer. The choreography was nowhere near the level of the playing from the pit. Least successful were the various attempts to get the ABT dancers to tap, on their pointes or in tap shoes; or to beat out rhythms with sticks. With the exception of James Whiteside, who has some actual tap training, the rhythms were jagged and unclear. It should be obvious but tapping, like ballet, takes years to master. Inevitably, the dancers looked, and sounded, out of their element.

Lauren Lovette’s Le Jeune, a pleasant, pert, but forgettable dance for ABT’s studio company, opened the evening. (The generic score, by Eric Whitacre, is particularly forgettable.) Its principal virtue was a bracing, youthful energy. Unlike the Dorrance piece, it suited the dancers and showed off their musicality and pristine technique. But it came as a relief when Twyla Tharp’s 1980’s extravaganza The Upper Room arrived to close the evening. What does it say about the artform when the oldest work on the program is the best, the most original?

Some may find Upper Room, with its booming Philip Glass score and baggy striped Norma Kamali costumes and sporty allusions to aerobics and cheerleading dated, but there’s no denying it’s a tour de force. Tharp keeps things moving for the duration: 40 minutes of jumping and running, often backward, leaping, tilting, knotty partnering, stomping, lunging, muscle-flexing. It pushes the dancers to the absolute limit of their stamina; by the end they’re gasping for air, and the difficult tosses and catches are beginning to look sloppy and perilous. The piece also captures the triumphal euphoria of America in the 80’s, a time of prosperity, influence, and self-confidence. And, certainly, brashness. This is made palatable by Tharp’s musicality – the juxtaposition of rhythms is thrilling – and keen sense of irony. The dancers are heroic avatars, but so over the top that you can’t help but laugh at (or with) their triumphalism.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

That said, I’ve seen Upper Room danced with more confidence and nonchalance. I remember fantastic performances a decade ago, led by Gillian Murphy, Paloma Herrera, Ethan Stiefel and Sascha Radetsky. They owned the ballet. In this cast, only Aran Bell and Herman Cornejo ( “stompers”), and Isabella Boylston (in the ballerina crew) rose to that level. In general, the timing was a little loose – so much of Tharp is about timing – and the technical difficulty of the ballet too visible. It will take a few more performances for the dancers to take its challenges in stride and make the tricks look like they are being tossed off, pas de problème.

The highlight of Thursday’s program was the return of Symphonie Concertante, a 1947 Balanchine ballet last performed by the company over a decade ago. (New York City Ballet doesn’t perform it at all.) I had never seen it before. What a joy to “discover” a new Balanchine work! The music, a delicate and courtly Mozart sinfonia for violin and viola (K. 364) is a sheer delight, if sadly, it must be said, both the violinist and the violist had trouble with intonation at times.

In style, the ballet combines elements of Symphony in C and Concerto Barocco, which, I suppose is why City Ballet has let it drop from the repertory. As in Barocco, two women lead, one taking on the profile of the violin, the other of the viola, and dance in conversation with each other. Like Symphony in C, it uses a huge corps, who often frame two or three sides of the stage or subdivide it in clean, mathematical patterns. It satisfies the part of the brain that loves to see dozens of arms and legs moving in beautiful, almost heavenly unison. It’s also one of those Balanchine ballets dominated by women, in which a man appears only to support the leads, discretely, modestly.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

So far, so familiar. But Symphonie Concertante is filled with wonderful surprises and felicities, the most striking of which, to my eye, is the complexity of the interactions among the women. Each soloist is brought on by a courtly retinue who surround her in a kind of cloud, holding hands. Later, the two soloists provide support for each other, standing in for the role usually executed by a male dancer. Even when the man arrives, the two women stay closely connected; the three form a geometric unit of exquisite complexity, in which one woman balances on one leg, while the other flutters around the periphery of her range of motion. When the trio departs, slowly, it is with a chain of women around them, slowly sweeping them off the stage. Another wonderfully suggestive detail is the moment in which the man turns around and faces the corps, walking slowly toward them, almost as if into a dream of his own imagining.

The soloists on Thursday were Christine Shevchenko (violin) and Boylston (viola); both danced with warmth and luminosity. Their relationship to each other was friendly, open. ABT’s approach to Balanchine is softer, less emphatic than, say, New York City Ballet’s. It’s a question of taste, but I would argue that a little bit more piquancy in the feet wouldn’t hurt. Even so, it’s a marvelous ballet and I hope it comes back again and again.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Friday’s program included another première: Jessica Lang’s Garden Blue, a collaboration with the visual artist Sarah Crowner. The commission is also part of ABT’s “Women’s Movement,” though Lang hardly needs to be promoted as an outsider. This is her 102nd work. The ballet is like a painting, a semi-abstract landscape suffused with rich colors. The backdrop, by Crowner, is a field of deep blue, as deep as a Corfu sky, with visible brushstrokes adding texture, and a corner of green on one side. Two wooden wing-like structures sit on the stage; another hangs above, like a fragment of a mobile. In their richly-colored unitards, the dancers, too, become slashes of color, activated by the lush, super-romantic music of Dvorak (the first three movements of the “Dumky” trio). The dancers move the wooden set pieces around, and interact with them, passing under, over, around, and between them, or using them as a frame for their poses. Everything is sculptural and lyrical, ravishing to look at. Hee Seo, in her white-and-green unitard, was particularly lovely. This is ballet at its most pictorial, more a series of moving tableaux than a story told through movement.

If you are looking for the latter, the ballet to see is Alexei Ratmansky’s Songs of Bukovina, created last year. There are only two more performances after this weekend. The music is a suite of piano pieces (“Bukovinian Songs”) by the Russian composer Leonid Desyatnikov, with motifs drawn from the folk music of Bukovina, a region in the Carpathian Mountains, in Ukraine. (Both Desyatnikov and Ratmansky have links to Ukraine.) Desyatnikov filters the songs trough various musical styles; each prelude has its own profile. One is Schubertian, another sounds like something produced by one of the French Impressionist composers; jazz and atonality make an appearance.

In response to these musical settings, Ratmansky creates a little world, strongly infused by folk dance. Heads bob, feet rap out syncopated rhythms. An air of mystery reigns. At the start, the dancers slide on, one by one, almost as if afraid of being discovered. They form lines and diagonals and snaking rivers of movement. Later, a couple (Shevchenko and Royal) walks on, slowly, regally. This introduces a calm interlude, almost ceremonial, made up mostly of walking steps. But the air of conflict and danger never fully lifts. Royal and a group of men dance a section, to martial-sounding music, in which they are like solders, fleeing from peril. Again and again, Royal struggles against a force that holds him captive. He and Shevchenko dance a staccato pas de deux in which they almost never touch, and their feet jab at the ground with jittery insistence. Shevchenko executes a circle of jumps, legs twisting in mid-air, as if dancing on hot coals. The ballet is full of stories, fragmentary and open-ended, less coherent than Ratmansky’s Russian Seasons, from 2006, but somehow related to that ballet.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

Bukovina has also matured since last year. The dancers seem to feel more keenly the connection between the steps and the rhythmically-complicated music. They find the accents, and that sense of contrast imbues the movements with more texture. The performance is also improved by having Jacek Mysinski, a company pianist, in the pit. (Might it not be more exiting to have him on the small platform to the left of the stage?) His playing has a strong rhythmic drive, and his familiarity with the dancers, and with the choreography, makes the ballet feel more like a coherent whole than it did last year. The costumes, which suggest folk attire, by Moritz Junge, are lovely; but the ballet still needs a more striking backdrop, some color.

Like Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free, also being performed this season, Bukovina makes the dancers look alive onstage, and emerge as individuals; it also opens a door to the expressive and narrative potential of ballet, beyond pure form. Ballet Theater’s richness lies precisely in the eclecticism of its repertoire. With eclecticism comes unevenness; some experiments, inevitably, are bound to fail. With time, others begin to reveal their true colors.

Marina Harss sees – and she sees so very, very well. Brava!