© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

Fall for Dance, Program #1

Boston Ballet: Bach Cello Suites

Sara Mearns: Dances of Isadora Duncan – A Solo Tribute

Caleb Teicher & Company: Bzzz

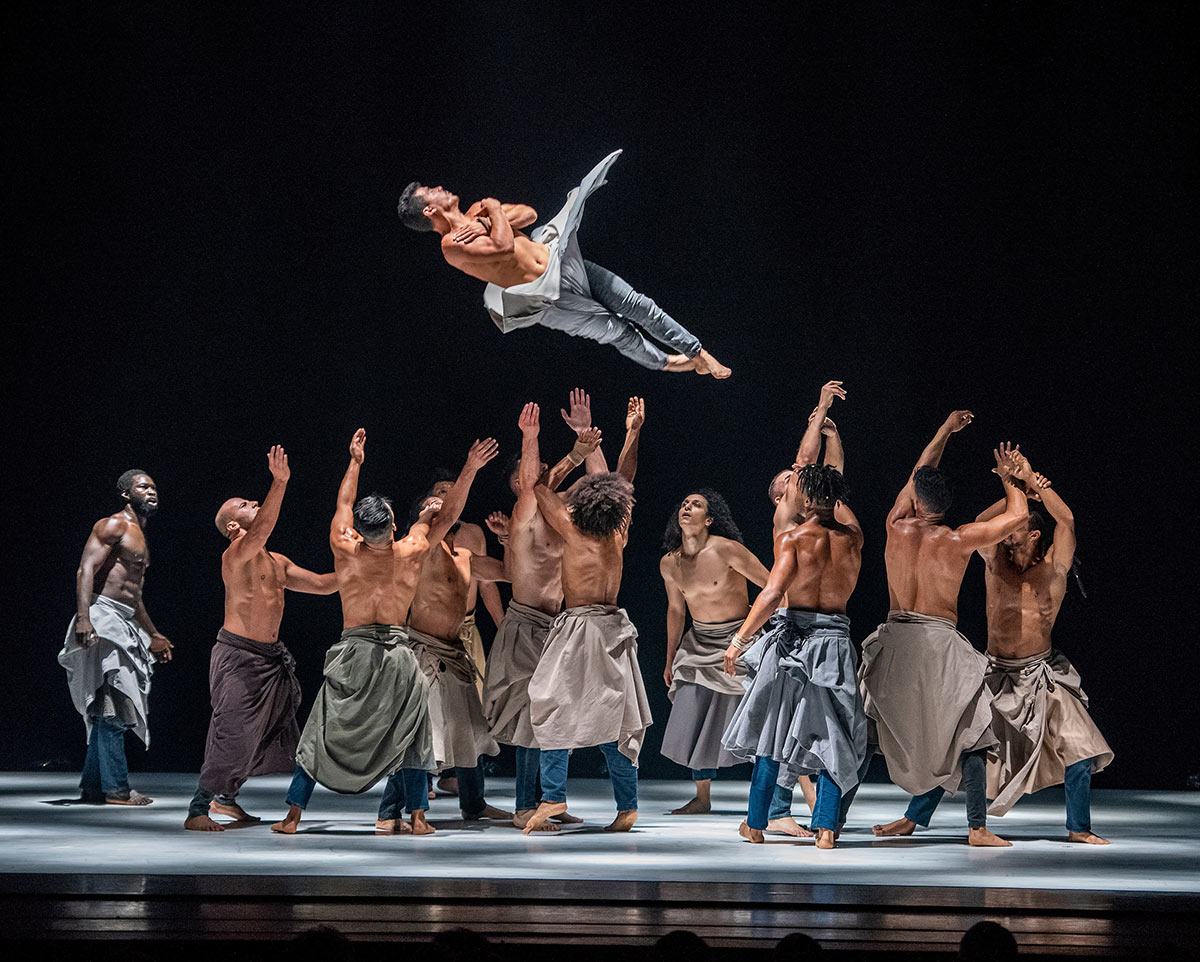

Cie Hervé Koubi: The Barbarian Nights, or the First Dawns of the World (excerpts)

★★★★✰

New York, City Center

2 October 2018

www.nycitycenter.org

When Sara Mearns, draped in a Grecian tunic and glory, entered the City Center stage to Isadora Duncan’s Rose Petals Waltz, the last of ten Duncan solos as recreated by Lori Belilove, she kept her thumbs pressed tightly to her hands, palming the eponymous petals which she’d soon rain about herself. Throughout these solos, Mearns had made exquisite use of her hands, tapping her wrists together as if coaxing a single clang from invisible cymbals, or, in Narcissus, to Chopin, doodling on the stage with her fingertip, drawing with greater delicacy and precision than I’m used to seeing in restagings of this dance. So, I was predisposed to pay careful attention to her hands, even thinking, as pianist Cameron Grant played Brahms, “here come the rose petals.” (Bear with me, I am going somewhere with this.)

It didn’t take long for Mearns to open her thumbs while swooping her arms about and let the petals swirl free. They fell prettily, but seemed a modest shower and hardly the deluge conjured by Mearns’ intensity. I wanted more petals, but her hands were wide open and she clearly wasn’t holding any more (I even checked with my binoculars). Yet as soon as I told myself to get over it, more petals appeared drifting about her, as if out of thin air. Although the surprise of this manifestation most likely came from inattention on my part, I’d rather think of it as magic, because Mearns had been working the same (however metaphorically), since she first appeared, on a literal and well-deserved pedestal, for Prelude Op. 28 (also Chopin).

© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

While Belilove’s choreography for Dances of Isadora Duncan – A Solo Tribute (“after” Duncan which has been passed down over the decades by a few of her artistic disciples) feels authentic, it’s harder to know precisely how Duncan moved, and whether she had anything like Mearns’ stunning dynamic range. Mearns has a grandeur and weightiness (not heaviness) verging on the monumental. In fact, it’s not hard to observe her and sense she’s sculpting her movements out of some sort of extra-dimensional clay you feel as much as see. (Laban might’ve called this strong.) It makes everything she does of great consequence. Yet she can also instantly express a startling lightness and speed, as in one of her earlier solos, to a waltz or mazurka (actually, all the solos seem to be waltzes or mazurkas). She simply ran powerfully across the stage, interleaving her broad steps with two tiny, quick, and close-together ones, rising for an instant on half-toe. It’s a brilliant accent, and her footwork sparkled much as if she were doing a pas couru (those rapid little running steps on pointe), and I wonder at how strongly her evocation of this dancer who notoriously had no use for ballet is informed by Mearns’ life as a ballerina. Mearns joins Seymour and Plisetskaya among ballerinas I’ve seen who’ve notably portrayed Duncan.

But Mearns’ sophistication and formidable technique counted mostly in how thoroughly she transcended them, or rather harnessed them in service of the look of rapture which seldom left her face. For instance, in one of the earlier solos, she’d repeatedly advance towards a downstage corner, then retreat from it, stepping away onto half-toe for an almost-pique almost-arabesque, her gaze lingering back at the corner she’d just vacated. She didn’t pose, but rolled through the arabesque, and her face grew more rapturous still, as if her entire existence was contained in the arc of her torso rising onto and over her standing leg. The arabesque was gorgeous, but seemed to exist, for Mearns, as much for the joy of creating it as for the aesthetic value of its shape. This step showed, writ small, the thrill of Mearns’ affect, and for an instant, we’re felt that rise and fall, too.

And for all that the amplitude Mearns gave to these simple dances looked to project to City Center’s farther reaches – her gaze, often beneath lidded eyes, seemed turned resolutely inward, an introvert playing an extravert’s game. I felt as if I were witnessing her prayer, an intensely personal and private moment in which we were privileged to participate. It was moving, affective, and an apt invocation for the beginning of New York City’s fall dance season, the highlight of the first program of City Center’s popular Fall for Dance season, which has become that season’s annual kick-off.

On the second night the program was offered, Mearns was stunning, but the remaining three pieces, by three different companies (Fall for Dance has always offered omnibus programming) were, to varying degrees, engaging, although hers was a tough act to follow.

The evening began with the Boston Ballet performing Jorma Elo’s Bach Cello Suites, for ten dancers, to Sergey Antonov’s sonorous cello. I’ve spent much of my life decrying the sort of ornamentations choreographers of a one-time European, modernistic bent are fond of imposing on what would otherwise be choreography that might well stand on its own two feet. In watching the Elo, I found I wasn’t as put off as I once would have been by things like dancers playing tag-you’re-it with each others’ heads, having an extended bit of movement in the silence between cello pieces, or ending with the ensemble, in tight formation, hitting a pose with their raised arms making Vs above their heads, their hands resolutely clenched into fists. Why? I have no idea. Perhaps I am mellowing in my old age, or perhaps this is a battle long lost. (On the other hand, this style has been around for decades and is a bit played out, and we’ve got a generation or two of excellent choreographers who don’t rely on such tricks, to make their work interesting.) Stripped of these curlicues, Cello Suites was a pleasant, if unexceptional, jaunt which approached the music with a certain amount of invention, and showed the dancers to good advantage – I particularly liked a section with Misa Kuranaga posing in fourth releve, like a contemplative stork transfixed by Bach.

© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

After Mearns came my first look at the work of Caleb Teicher, as Caleb Teicher & Company presented Bzzz, a new work commissioned by Fall for Dance. Its music a rousing collaboration between beat-boxer Chris Celiz, and the tapping shoes of Teicher and his seven dancers, Bzzz was as much a delight for Teicher’s dry wit as for the merry cacophony and casual genius of its performers. Most of the dancing was compressed into a narrow downstage corridor defined by three resonating platforms (to better amplify the tapping) and the spaces between. It began with one dancer tapping on a platform, then joined by another and another until all seven dancers were compressed into that small space, the arrival of each drawing chuckles as the ensemble adjusted itself to the seemingly impossible task of accommodating the next person in. Much later, Teicher and Demi Remick find themselves side-by-side downstage, their gyrations reduced to each monotonously tapping a single foot while feigning boredom, Remick shading her eyes to inspect the theaters upper reaches. Teicher even made a little dance for Celiz. It strains a bit my command of words to adequately describe the delights of this piece. I was enthralled, particularly by Byron Tittle’s gangly and peripatetic solo.

© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

This rousing program came to a rousing finish with Cie Hervé Koubi performing an excerpt from Koubi’s The Barbarian Nights, or the First Dawns of the World. Described in the program as a group of Algerian street dancers that Koubi has been working with since 2010, these thirteen men make an impressive sight, muscular and bare-chested, as they tumbled and tossed each other through an array of acrobatic moves, hearkening to hip-hop, copoeira, and I couldn’t begin to classify. Most astonishing to me were what I’d call inverted pirouettes, where a dancer would place both, or one hand on the stage, balancing and spinning around it. When they weren’t doing steps like these, or somersaulting across the stage in high aerial flips, or tossing each other even higher, they paced calmly about the stage with gravitas, singly or in groups that seemed to coalesce and divide like schools of fish, from which more acrobatic feats might emerge, as if organically. Despite their speed and the height of their leaps, they performed these with the same weighty softness as their beautiful, simple walking, all with a weightiness and substance not far removed from that which impressed me so with Sara Mearns, and, catlike, they landed soundlessly from their most spectacular leaps. As the piece wandered gradually from Maxine Bodson’s atmospheric and vaguely Middle-Eastern rhythms to the chords of a Mozart chorale, the dancers arrived at a unity of togetherness, suggesting we’d just watched the organization of order out of chaos. Then it was over, except for the cheering, which went on for a good bit longer.

It is simply grand to see Eric Taub back contributing to Dancetabs, eloquent as usual, detail superb and clearly satisfied by what he observed. In General, Hooray!!!!!

Thanks, Renee!