© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Lazarus, Revelations

★★★★✰

New York, City Center

30 November 2018

www.alvinailey.org

www.nycitycenter.org

Forward to Ailey

In March of 1958, Alvin Ailey presented his first evening of dance, at the 92nd Street Y. Sixty years on, the company is going strong, having survived the death of its founder in 1989 and the successful transfer of leadership from Ailey to Judith Jamison, and from Jamison to Robert Battle. By all accounts, the company is thriving; it recently expanded its beautiful headquarters in Hells Kitchen, the school is full of students, performances are packed, and, under Battle, the repertory is expanding in interesting ways. It’s true, there have been some labor issues of late, but they do not seem to threaten the future of the company. If anything, they are a sign of its success, which the leadership would do well to share with the dancers.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

So, to mark its sixtieth anniversary, the company is throwing itself a celebratory season with two new works and various other highlights. The first of these, the premiere of Rennie Harris’s Lazarus, took place on the evening of Nov. 30. It’s an ambitious hour-long, two-part work – the company’s first – conceived as a tribute to Ailey’s life and spirit. In reality, its themes seem both broader and more personal. Harris, perhaps America’s most admired and philosophically-inclined hip-hop choreographer, tackles nothing less than the African-American experience. In this sense, he is walking in Ailey’s footsteps.

It’s a tricky thing to fulfill such lofty goals, but in aggregate, one can say Harris succeeds, though the first half of Lazarus feels overlong, weighed down by some excessive repetition. The main image, which comes back again and again, is of a man collapsing, gasping for breath, and dying in another man’s arms, then returning to life, like his namesake in the Gospel of John. In this cast, the dying man was played by Daniel Harder; the man who tended to him was Jamar Roberts. It’s not the first time Roberts – tall, powerfully built, with an inexplicable gentleness – has been cast in an angelic, caring role. Many choreographers seem to see him in this light.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The image of a man falling and being tended to by a grieving community also finds echoes in another work by Harris, the 2015 Exodus, which also dealt with themes of suffering and redemption. As in that work, Hope Boykin, one of Ailey’s senior dancers, was the embodiment of inconsolable grief, wracked by loss. But there is more than sadness and loss in Lazarus. Dancers show everyday work – picking cotton – prayer, and the release of dance. They run, protest, shield each other from invisible attackers, evoking the Civil Rights movement. The barking dogs and fire hoses of their tormenters ring through Darrin Ross’s score, which, collage-like, also contains songs by Nina Simone, Michael Kiwanuka (“Black Man in a White World”) and Terence Trent d’Arby.

And there is dancing, particularly in the second section, in which Harris introduces an infectious rhythmic motif derived from “rhythm house,” a hip-hop style from the eighties. The footwork is hard-driving, fast, simultaneously gliding and percussive. Combined with the musicality, attack, and dedication of the Ailey dancers, it becomes immediately exhilarating.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

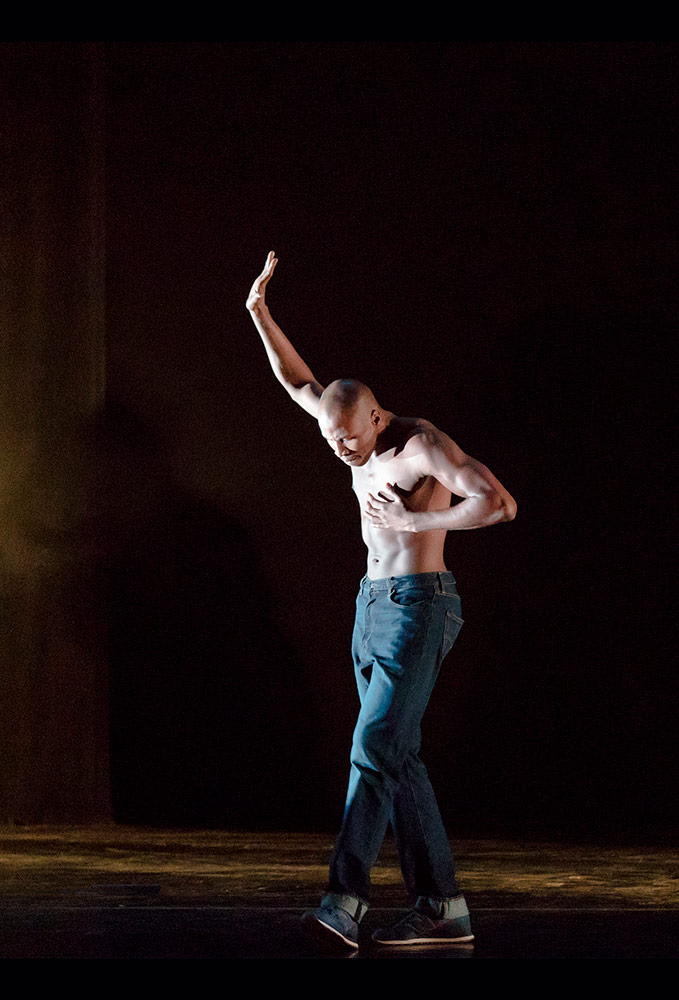

This second section was dominated by Jeroboam Bozeman, another tall, powerfully-built dancer. Unlike Roberts, though, Bozeman is sharp and hard-hitting, with the attack of a man who won’t be denied. His footwork has bite; his arms and back move with angular force. Harris has devised an extraordinary solo for him, with swiveling hips and jerky arm movements; meanwhile, his feet jab and glide. The upper and lower body seem to move to different frequencies. From that point on, the energy builds and builds, driven by Darrin Ross’s beats. Groups enter, cross, meet, disperse; the energy is kept high, but constantly shifting, never monolithic or overwhelming.

After this ecstatic passage, Harris re-introduces a philosophical note: an imaginary conversation with Alvin Ailey, created by cobbling together bits of a recorded interview from the 1980’s. In the recording, Ailey speaks of “blood memories,” images from his mother’s, and his mother’s mother’s life, that return so often in Ailey’s work (particularly, of course, in Revelations). Harris muses about the current state of things, the shootings of black men that we hear about all too often on the news. This ending is perhaps a little over-literal, an attempt to wrap things up neatly. And yet it feels undeniably timely, and honest. There is so much still do be done.

© Christopher Duggan. (Click image for larger version)

The evening closed, as so many evenings at Alvin Ailey do, with Revelations. As always, it worked, despite a varied cast and a slightly underwhelming finale. (They can’t all be barn-burners.) It was a pleasure, though, to hear musicians and singers in the pit, rather than the old, timeworn recording. This was one of a few Revelations over the course of the season that will have live accompaniment. One can see the line from Revelations to Lazarus–the striving for purpose and storytelling and truth through dance. The sense of continuity at Ailey is strong.

Marina, as always, manages to capture in words the overall acrc of an important

piece, presenting its physical qualities while not get lost in the recitation of specific

moves. It’s a wonderful gift, both objective and illustrative of her personal responses.

I never tire reading her prose.

I’m honored by your words, Renee.