Boston Ballet

Simply Sublime: Les Sylphides | Polyphonia | Symphony in Three Movements

Boston Opera House

February 2012

www.bostonballet.org

Last week at the Boston Opera House, Boston Ballet inaugurated its 2012 season with a program of three classics, two old and one new: Les Sylphides by Fokine in a new staging by Florence Clerc (formerly of the Paris Opera Ballet), Polyphonia by Christopher Wheeldon, and Symphony in Three Movements by Balanchine.

When Fokine choreographed Les Sylphides for Diaghilev’s first Ballets Russes season in Paris in 1909, he inspired a revolution, for it was the first plotless ballet ever created. By now we’re so used to plotless or abstract ballets, thanks largely to Balanchine, that it’s impossible to recover the shock of Fokine’s first audiences. To us, the ballet looks like we imagine late 19th century Romanic ballets should look: geometric formations of ballerinas in calf-length tutus discovered in a moonlit forest glade wearing floral garlands, arms bent and hands cupped at their breasts, heads inclined in an attitude of pensive melancholy. Save for the fact that they’re in white, they could have stepped out of a Degas pastel.

I was nervous about this new staging of Sylphides because it’s a work that demands first-rate presentation; anything less and it’s dead in the water. Some works can survive with second-best—most of Shakespeare’s plays work well in high school productions—but Les Sylphides requires an excellent performance or it fails miserably. I needn’t have worried: Clerc’s version works admirably. She maintains the 19th century romantic mood, but the architecture of the whole is now more clearly articulated and the four soloists emerge with stronger identities.

Opening night, the lead couple—Lorna Feijoo and Nelson Madrigal—were merely adequate. The other leads—Erica Cornejo and Whitney Jensen—were in good form, with Jensen giving an especially impressive performance. Jensen improves each season, claiming each role fully, and in the past year she has become one of the dependable delights of the company. The corps, second among equals here, was exemplary. And Benois’s original set—a ruined Gothic graveyard—contributed nicely to the melancholy of the whole. At the third performance, the leads were James Whiteside, Misa Kuranaga, Delay Parrondo, and the inestimable Kathleen Breen Combes. They were so superior to the two previous casts that you wondered where they were on opening night.

Christopher Wheeldon’s 2001 Polyphonia is acknowledged as one of his finest works. Set to ten piano pieces by Ligeti, it shows great imagination in its combination of classical steps and modern movements (rolls and twisting turns, quirky hand movements and cartwheel lifts). Roughly divided between fast and slow movements, it requires precise and intricate footwork from its eight dancers, who in a profusion of duos and trios, quartets and ensembles, convey the impression of an entire company. Occasionally Wheeldon freezes the action, as in the horizontal lifts at the end, providing visual respite from the frequently manic goings-on.

The first etude presented four couples dressed in purple tights and going through rapid-fire paces while showing us the vocabulary of the piece. In the second etude, Lia Cirio and Sabi Vargas performed a study of extensions and contractions, like a series of flowers opening and closing in slow motion. In etude five, Paolo Arrais and Joseph Gatti extended the emotional range of the piece with some frat boy hi-jinks, by which point we had been treated to fast/slow, joyful/solemn, playful/serious. This textural and emotional richness kept growing. Sometimes a piece began the way an earlier piece ended, making evident Wheeldon’s careful patterning. The tenth piece opened with an echo of the second ending, geomorphic shapes slowly opening and closing, though now the flowers were insects. Complicated passages often resolved themselves into simple conclusions. Overall, the piece demonstrated a confident sense of form, made evident by eight excellent performances.

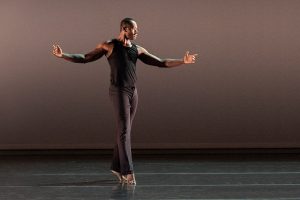

Though nearly three decades older, Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements feels even more contemporary, suggesting yet again that this was an artist for the ages. The ballet was one of two new ballets he created for the celebrated Stravinsky Festival in 1972, and from its premiere it has been recognized as one of his greatest accomplishments. It begins with one of the most striking tableaux in all of ballet. The curtain rises on a floodlit stage with a blue backdrop and a diagonal of sixteen pony-tailed women in white practice clothes and toe shoes. As Stravinsky’s jagged, percussive chords blare forth, the women whirl their arms in unison, step forward, and break into contrasting lines, the odd-numbered women doing one thing and the even-numbered another. Sometimes they mirror each other’s movement but not always. They begin prancing about the stage as two soloists explode from the wings (the splendid Jeffrey Cirio and Misa Kuranaga on opening night), both leaping in jagged jumps with knees together and legs bent. We’re far away from the Imperial Ballet School in St Petersburg where the young Balanchine received his training.

The first and third movements are crowded and breathlessly energetic, the middle section much quieter. Classical steps are joined throughout with jazzy, Broadway movements that make for a dizzying combination. Every moment is saturated with invention, the eye constantly dazzled as these startling fireworks proceed. The ending is as visually arresting as the beginning: 32 dancers assemble on stage, the women standing with arms straight out or overhead as if sending semaphore signals into outer space, the men crouched along the apron of the stage ready to sprint forward toward the audience.

It’s become a cliché to say that in Balanchine’s best works we see the music, but that’s especially true here. In 1947, only a year after Stravinsky created Symphony in Three Movements, Balanchine wrote of Stravinsky that “When I listen to a score by him I am moved to try and make visible not only the rhythm, melody and harmony, but even the timbre of the instruments for if I could write music it seems to me this is how I would want it to sound.” And Stravinsky wrote of Balanchine “I do not see how one can be a choreographer unless, like Balanchine, one is a musician first.” This collaboration of two of the giants of 20th century art was clearly a marriage made in heaven, and thanks to Boston Ballet’s newest production, we got to attend the nuptials.

Most of the dancers performed well, but those who gave special delight were Jeffrey Cirio, Kathleen Breen Combes, Whitney Jensen, Misa Kuranaga, and James Whiteside. Freda Locker was the excellent pianist for Polyphonia. Aside from a sluggish Sylphides, Jonathan McPhee conducted the orchestra with his usual aplomb.

You must be logged in to post a comment.