Kings of the Dance

Jazzy Five, Kaburias, Labyrinth of Solitude, Still of King, Guilty, Tue, KO’d

New York, City Center

24 February 2012

ardani.com/kings

Apparently, when you’re a King of the Dance, every day is a bad hair day. Or at least last Friday was, as the third incarnation of this ever-popular Chippendales, I mean, Ardani Artists Management, road show opened its brief visit to City Center. When I wasn’t idly hoping that after the program a merciful M104 bus might run me over and spare me the need of writing it up, or observing, with less pleasure than you might imagine, that my Overhead Spot Law of Bad Choreography {*} (as well as its Shirtless Corollary {**}) remained in full effect, I had ample time to ponder that, just as I had for most of the Seventies, I was again watching superstar male dancers laboring under the burden of overachieving big hair. (Can fat ties and wide lapels be far behind?) Of course, if I hadn’t been so transfixed by the crinose crowns of this dance royalty, I might’ve focused more on, well, the dancing, so thank heaven for small favors.

So, we had Guillaume Côté sporting le mullet (“affaires dans l’avant, fête dans le dos”),and Ivan Vasiliev manfully bearing up under a small Vesuvius of curls. Thankfully, Marcelo Gomes, the class act of the evening, kept his black hair slicked tidily back to his scalp (and how I longed for him to give it a vainglorious little pat with the palm of his hand, as when he’d acknowledge his applause as Espada at the Met). David Hallberg’s blond pageboy, um, Prince Valiant, was mostly innocuous, except when dangling from his head as he posed upside down, which, unfortunately, he’d do with some regularity. However, it was the kinder, gentler, and happily softer version of Callista Gingrich’s celebrated blonde hair helmet worn by Denis Matvienko that truly gave pause, not the least of which because, floating cloud like above his not inconsiderable brow, it had twice the ballon of his feet.

It may seem disrespectful of me to go on at such length about these men’s grooming choices, but it speaks to the saddest of the evening’s many failures, that one might look at these incontrovertibly great artists, and assume that much of the business of being a ballet superstar is to model such over-the-top stylings. That, and a gift for entwining one’s forearms into double-jointed knots while spasmodically thrusting one’s hip akimbo, and, not at all least, a penchant for displaying a chest and torso that haven’t seen the light of day since the millennium. And of course this isn’t true. You know it, I know it, and even the annoying Russian guy seated behind me who wouldn’t shut up throughout the performance knows it.

Whatever else being a ballet star is about, it’s first and foremost about brilliance, and bravura—replacing our mundane, everyday physics with classicism’s sublime and miraculous beauty. In other words, lots of really great jumps and turns. And while such can easily descend to the circusy depths of ballet-gala tricks, I’d have preferred a good, honest pander, however vulgar (and remember, Balanchine would often exhort his dancers to be more vulgar) to this program’s willfully contrary artiness. If you’re going to eschew the blindingly obvious (e.g., bravura) you’d better replace it with something wonderful, which this program of trite, predictable, cut-from-whole-cloth Pina-on-the-half-shell clichés, wasn’t.

The most astonishing thing about Mauro Bigonzetti’s Jazzy Five, which opened the program, isn’t that it takes these five great dancers and makes then look like adorably precocious, gauche high school kids who’ve stolen out to a dance club, showing off their chops between displays of mawkish male-bonding. Nor is it that Igor Chapurin has dressed them in slacks and sports jackets with rolled sleeves, much as if they’d raided their parents’ attics for some castoff finery from the mid-Eighties of Miami Vice.It’s that the worst contribution by someone named Bigonzetti isn’t the too-familiar eccentric choreography, but Federico Bigonzetti’s dreadful music. Performed by a group called Jazzy Dogs (one sees a trend here?), it ranged from bad techno-pop to excruciating love songs, unintelligible despite being in English, sung by a vocalist as overbearing and fuzzy as the syntax of the word-salad lyrics.

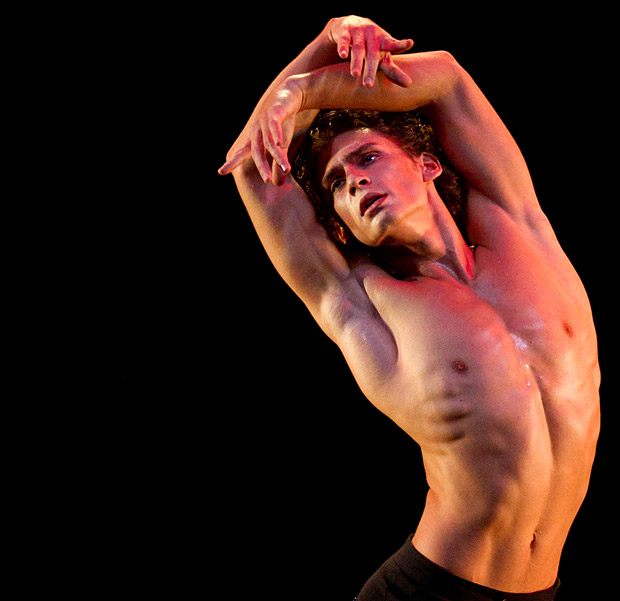

It began, as do many Bigonzetti ballets, with movement to silence, in this case Gomes in the puddle of light beneath an overhead spot slowly working his way through the kind of body-part isolations so dear to this style. I don’t know why it should be so fascinating that a dancer’s elbow folds properly, or why Bigonzetti must have him demonstrate this by ignoring the perfectly good muscles surrounding said elbow, and having it hang limply while being held and manipulated by the other arm. If one must see this sort of thing, who better to do it than the magnificently articulate and sophisticated Gomes, who, once again, demonstrated his talent for making silk purses of sows’ ears.

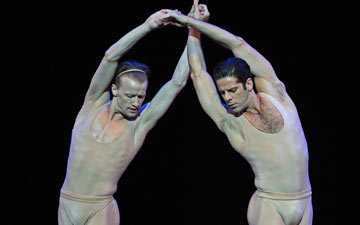

He was quickly joined by the aforementioned blaring soundtrack, and his compatriots. They draped their arms over each others’ shoulders as if they’re about to dance a hora, then, hardly surprisingly in such a piece d’occasion, took turns dancing solos that, perhaps more in intent than execution, looked designed to show off each dancer’s unique qualities, although few stuck in my mind more than than Hallberg’s lugubrious love-ballad adagio, showing off his singing legato line with high extensions and poses that veered dangerously close to classical purity for a Bigonzetti work. Vasiliev, as we were to see later in the night as well, at least got to throw in some zippy pirouettes and turns across the stage. (As they stripped off their jackets, I pondered ensembles in which not even Don Johnson would be caught dead, as with Matvienko’s double-breasted vest over a nondescript T-shirt.)

Mostly, though, they danced a Bigonzetti ballet. While I’ve at times been entertained by his work, it’s usually been in spite of his actual pinched, navel-gazing vocabulary, which, in a chamber work like this, it was impossible to allow my eyes to glaze over. So, we were treated to the dancers repeating (and repeating and repeating) a rococo motif of twining, fluttering arms, much as you might see in a circus clown frantically inflating and knotting a long, skinny balloon into a wiener dog, then setting it free with a cheery wave of his hand, except there were no actual balloons, or, for that matter, red noses. There were also the requisite Bigonzetti bits of slappy-face, here presented as farce rather than violence, and, absent any ballerinas who might plunge their toeshoes vampirically into the mens’ chests, he made do with the men’s own pointing index fingers, in a jocular, I suppose, way of saying “Tag, you’re it.”

When all else fails, and it did, Bigonzetti could hardly have done wrong in concluding his piece by sending Gomes back out for a topless solo. He fairly lit up the theater with the twin beacons of his sheer kinetic intelligence, and the unwaxed gloriousness of his buff, hirsute physique. I could only wish Bigonzetti had made his move sooner, and the stage had not been so cluttered by those four (I think there were four?) other guys.

After the intermission, things got truly depressing, as the men took their turns at dancing what proved to be the same damn solo, disguised only slightly by differences in costume, music and titular choreographer. Dancers appeared, as often as not, bare-chested beneath overhead spots, and demonstrated, repeatedly, their facility for waving their hands about, tracing invisible curlicues in the spaces about them. However each piece related to its particular score, they all appeared, much like Bigonzetti that preceded them, as accretions of random, unrelated bits, and it all too easy to overlook the dancers’ individual genius and see each choreographer improvising as he went along.

In Kaburias, Nacho Duato’s solo for David Hallberg, it was, perhaps, audacious to present the man with the Most Beautiful Legs on the Planet™, swaddled below the waist in a ruffled, black, sarong-like wrap, so that said legs wouldn’t distract us from admiring the use of his pasty midwestern torso. Certainly this choice was well in the evening’s contrarian spirit; it was also ridiculous. For all that Hallberg hopped about in a deep-seated second position, or paced beatifically about the stage and draped himself off its edge like Christ down from the cross, I couldn’t for the life of me see what this had to do with greatness, either Hallberg’s own, or that of regal male dancers in general. Also bare-chested, Côté similarly noodled about, twitching and fluttering his hands to the singing of one Barbara, sounding very much like Piaf on amphetamines, in Marco Goecke’s Tue. He, too, had his rolling-about-on-the-stage moments, although, unlike Hallberg, he didn’t threaten to end up in the laps of those sitting in the front row. Matvienko’s solo, Guilty, by Edward Clug, was much the same, except it was set to Chopin and he actually wore a shirt, black, so that might better admire his hair’s floating luminosity.

Shirtless, waxed and glabrous, like Hallberg and Côté before him, Vasiliev also had too many self-consciously quirky moments in Patrick de Bana’s Labyrinth of Solitude, set to Tomaso Antonio Vitali’s Ciaconne in G Minor for Violin and Piano, but unlike everyone else on the program, he also got to to cut loose with some good old-fashioned bravura, blasting off cyclonic pirouettes in second, a high-flying 540 into a log-roll, then lassoing the stage with a buoyant chain of jeté coupés. The audience went nuts, yelling and applauding, and even the Russian guy behind me knocked off his running chat with his date to bellow out something I’m sure was suitably encouraging. Normally I roll my eyes at such displays of uncouth, naive enthusiasm, but I was mostly relieved that, finally, the audience had gotten some of the ballet magic they’d so clearly come here in hopes of seeing. It was, alas, just about the only time.

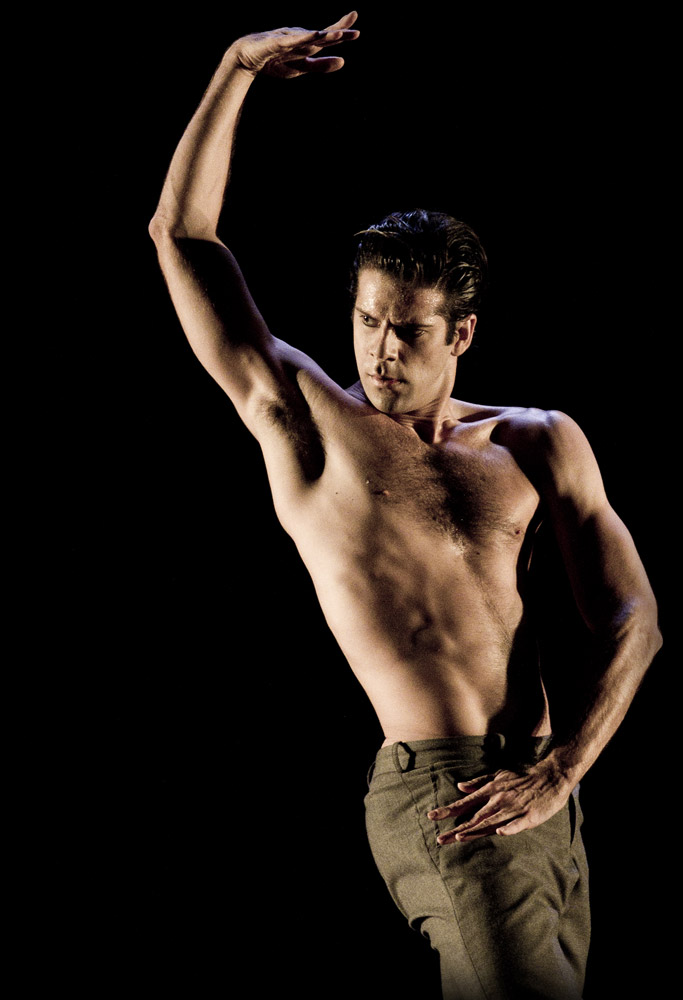

Gomes did much more for Jorma Elo’s Still of Kingthan it did for him, but what else is new? Dressed to ballet convention in white tights and bloused shirt, he looked every inch the prince. To the adagio movement of Haydn’s Military Symphony, he played fast-and-loose with danseur-noble traditions, alternating between elegant arabesques and cornier, vernacular gesture, favoring the audience with a thumbs-up or thumbs-down as if he’d just invented it, and was pleased with himself for having done so. The finest actor I’ve ever seen in ballet, he invested Elo’s trivialities with such clarity of intention, you could almost read them as a witty, stream-of-consciousness response to the Haydn’s ever-shifting moods. Or you could, until you thought about it a bit, and realized Gomes wasn’t so much Duse reciting the phonebook as, perhaps, selected works of Henny Youngman.

KO’d, which concluded the program, reminded us that there are choreographers whose works are beyond salvation by even the mighty Gomes, in this case, Gomes himself. Bringing back all hands, and dressing them in a sort of inverted Balanchinian ensemble of black shirts and light-gray tights, KO’dhad the five bounding about in steps that were as happily free of the preceding works’ tics and twitches as they were forgettably bland. No blander, though, than the score, the Piano Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major by one Guillaume Côté. It was hard not to look at much of Gomes’ work as filler leading up to the big surprise when the upstage drop rose to reveal Côté himself, briefly off to play the grand piano.

I apparently did not have a rendezvous with the 104 on Seventh Avenue, so I will just conclude with noting that another depressing thing about the evening’s kitsch-ridden choreography was that it didn’t quite obscure the occasional glimmers of brilliance that reminded us that these men are, indeed, among the world’s best, despite this tawdry presentation. (I’ll leave go for now the depressing thought that these Kings might have liked this stuff.) Even in the Bigonzetti, I thrilled to the luminosity of perfect grand jetés delivered en masse. I’ve mentioned Gomes’ keen intelligence, and whenever you could actually seeHallberg’s legs in the Duato, it was payoff enough, almost. Côté showed hints of a powerfully molded plastique, and Vasiliev phenomenal clarity and lightness, even in the midst of his most frenetic tricks. And, well, did you ever notice how Matvienko looks like Daniil Simkin’s bigger, older brother? (Sorry, Denis, I got nothing.)

* Any dance that begins with a dancer beneath an overhead spot is going to be awful.

** If he’s bare-chested as well, it’ll be really, really awful.

Eric: Your inimitable words rather bring an end to a week’s worth of pretty downbeat reviews from NY colleagues for this show. We’ve had some similar events over here, of course, where the pursuit of a ‘concept’ appears to smother good judgement – a great pity when there are otherwise top talents on parade. As to the hairdos, next year’s Kings could well include the now-solo Delphic tweeter, Sergei Polunin, when you’d have hair plus tattoos.

your analysis a lot of fun, LOL