San Francisco Ballet

Program 5: The Fifth Season, Symphonic Dances, Glass Pieces

Program 6: Raymond Act III, RAkU, Guide to Strange Places

San Francisco, War Memorial Opera House

21, 23, 27 March 2012

www.sfballet.org

In a forward-thinking move last year Artistic Director Helgi Tomasson set up the New Productions Fund to enable the San Francisco Ballet to acquire more pieces for the repertoire, either by restaging ballets created on other companies or commissioning new work from established and upcoming choreographers. With the former you already know what you’re getting, although different dancers can reveal or obscure various elements of the choreography. With the latter you can be surprised, positively or negatively, as we shall see on each of two programs premiering works by choreographers new to SF Ballet.

The Fifth Season, opening Program 5, is named after the first movement of Karl Jenkins’s String Quartet No. 2 which accompanies it. The addition of the Largo from his Palladio makes six movements. I find it interesting that Jenkins is described in the program booklet as a minimalist composer, though he does not belong with Glass, Reich, Adams, or Pårt. In fact, he covers the gamut and was only influenced by minimalism. The choreography does at least match the easily-accessible score, with other movements named Waltz, Romance, Tango and Bits.

Frances Chung and Davit Karapetyan lead off the first movement. He moves with luscious sensuality while she seems a bit too entrenched in technical proficiency. Chung used to have a brilliant warmth and buoyancy that I want her to reclaim. The ability to light up the stage is so much more essential than perfect pirouettes. In the Tango, the alluring Sarah Van Patten has the trio of men wrapped around her finger. As always, the audience adores Yuan Yuan Tan and Damian Smith in the adagio to the Largo. Smith is in the class of consummate partners, men with the innate gift to support and enhance the woman without showing the physical effort, of giving to her without diminishing his own interpretation of his role.

The world premiere of Edwaard Liang’s Symphonic Dances, also named after the music by Rachmaninov that Liang employs, looks a bit under-rehearsed. In the first moments it is clear that different groups of dancers have different ideas as to whether a step emphasizes the downbeat or the upbeat. So I decide to return when they have settled in and I can fairly evaluate the performances of the dancers. When I come back six days later, the dancers have indeed put the choreography into their bodies. The lead couples – Yuan Yuan Tan and Vito Mazzeo, Sofiane Sylve and Tiit Helimets, and Maria Kochetkova and Vitor Luiz – are excellent in each respective pas de deux, and the group of men led by soloists Daniel Deivison and Isaac Hernandez are riveting.

The choreography is quite eclectic, reflecting Liang’s own diverse history of dancing with New York City Ballet, the Broadway show Fosse, and Nederlands Dans Theater. The result is what happens when you take the styles of all the major choreographers of those companies, e.g. Balanchine, Robbins, Fosse, Kylian, and use a metaphorical Ouija board to link them together. I think a quote by Liang from the program booklet puts it quite well: “People ask me how I choreograph, and I really have no clue. For me there is no recipe. I’m just lucky that I get to do what I do.” I prefer a choreographer who has a distinctive voice, one who can put his own personal and recognisable stamp on his work.

While Symphonic Dances has long stretches of lyrical, swirling movement, there are also a few very awkward lifts in several of the pas de deux. Putting it politely, one such is the odd sight of a crouching woman being lifted with her derriere en l’air as the leading body part. A leg extended into an attitude or arabesque would solve the problem. Despite these shortcomings, the enthusiastic applause trumps all.

How extremely fortuitous that the evening ends with Jerome Robbins’s Glass Pieces, saving the best for last. The complexity of the construction of this ballet to music by Philip Glass allows for new discoveries and explorations of its intricate architecture. My only complaint is that the costumes from 1983 look very dated, particularly those for the women in the corps de ballet. The short chiffon skirts turn them into 13-year-old girls instead of adults. This revival lifts me over the two previous ballets and reconfirms my preference for the tried and true over the newly-minted mundane.

Two nights later Program 6 opens with Raymonda Act III which has been out of the repertoire for more than a decade. In 2000 SF Ballet imported the third act of the Nureyev (after Petipa) version of the complete ballet created for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1983, and staged here by Patricia Ruanne with costumes and sets by Nicolas Georgiadis. This time around it is the one-act version made for the Royal Ballet Touring Company in 1966 that includes solo variations from Acts I and II and is mounted by Grant Coyle, assisted by Bruce Sansom.

The curtain rises on the opulent set and costumes by Barry Kay courtesy of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. The massive scenery looks like it was meant for a larger stage and the result is claustrophobic. The sumptuous white costumes shimmering with diamonds and gold are almost too luxurious for those who prefer restrained elegance. The dancing, on the other hand, is restraint verging on frigidity. What a pity Lorena Feijoo is out on maternity leave. She would have spiced up this Hungarian goulash with some paprika.

To be fair, the technical demands of the solo variations are demonic, especially when done at slower tempi. Success in their execution here seems to mean the loss of the dancers’ souls in a Faustian pact. All these dancers are capable of shading and highlighting the steps, so went wrong? As in most of the narrative ballets performed by this company, the dancers appear to lack coaching in how to create the proper ambiance, to provide a historical setting to frame the action. The point of the third act of Raymonda is both honoring the King of Hungary by performing his native dances and celebrating a marriage. They should look like they are having fun. And then, how many of these dancers have ever really studied character dance? It used to be part of the training curriculum in the old days, but now has been relegated to the dustbin. Thankfully, Elana Altman, as Countess Sybille, beguilingly flashing her eyes and inclining her head with a knowing air, is perfectly in character, with sympathetic support from Pierre-François Vilanoba as the King of Hungary.

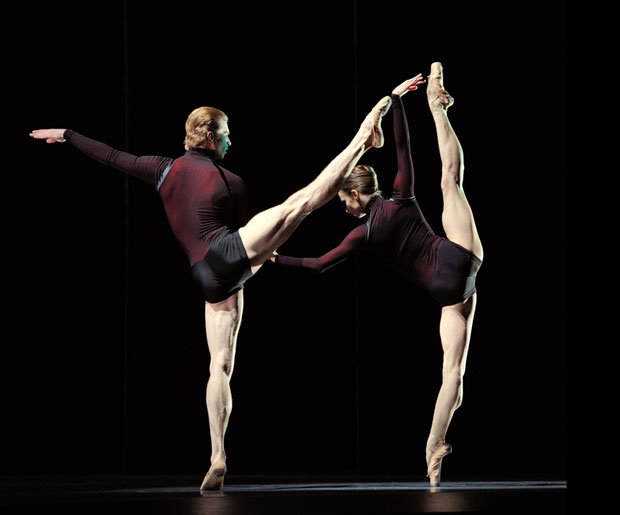

Choreographer-in-Residence Yuri Possokhov’s RAkU premiered last season to great acclaim and is definitely an audience favorite. I thought it had too many intense visual elements originally, but this season’s performance seems more controlled, or perhaps I have learned to narrow my focus. I appreciate once more Possokhov’s inventive choreography filled with steps you’ve never seen before, phrases that suggest they will move in one direction only to go in another, a blending of both unison sections and canonical ones. He also has the ability to draw out the best in his dancers. Using only seven dancers, three main characters and a group of four men, he can suggest a story that in other hands would need dozens to make its point. Yuan Yuan Tan and Damian Smith, paired as the Princess and her Samurai husband are eloquent, while Pascal Molat is superb in portraying the Black Monk who is obsessed with the Princess.

To conclude the evening Ashley Page, Scottish Ballet’s Artistic Director, premieres his Guide to Strange Places. Again, the title of the music provides the name for the ballet (can’t choreographers be a bit more creative?) and composer John Adams is a bona fide minimalist. I have never seen Page’s work before so I have no context for this new ballet in relation to his oeuvre.

Calling this ballet a guide is not really precise because it’s more like a portal that lets you in and then leaves you on your own to figure out where you are. Whether you have absolutely no sense of direction or can find your way anywhere blindfolded could determine how you explore this terrain. The format is one where a pas de deux will emerge out of an intense mass of energetic dancers with this pattern repeating until all four of the principle couples have had their moments in the spotlight. Think of driving in the mountains surrounded by peaks; suddenly you round a curve and glimpse a charming village in a grassy valley, then later, around other bend, you catch the brief flash of a lake reflecting the setting sun. Beautiful, of course, but the real question might be why are you driving in the mountains in the first place.

The dancers are excellent, no question about that, and I am intrigued by the use of space, often employing asymmetrical patterns, and with the focus not directed at the audience. Wandering has its limits and I really long to be shown a unique perspective, to be taught an unknown language, to have an authentic guide to the artist’s intentions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.