La Scala Ballet

Marguerite and Armand, Concerto DSCH

Milan, La Scala

3 May 2012

www.teatroallascala.org

La Scala Ballet is often dismissed as a company without depth, a haven for international guest artists living on a steady regime of full-length ballets. And yet Makhar Vaziev, who left the Mariinsky to take the helm in Milan in 2008, has been taking on more ambitious projects, one baby step at a time. Last October, Sergei Vikharev’s Raymonda reconstruction brought the company together with admirable results, and this month, Vaziev is introducing another Russian luminary to Milan: Alexei Ratmansky, who set his Concerto DSCH on the company. Paired with Frederick Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand, it made a much-needed case for one-act ballets on a stage where, sadly, no other mixed bill is scheduled through the end of the 2012-13 season.

Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand was last seen in Milan in 2004, with Sylvie Guillem and Massimo Murru as the famous lovers, and La Scala revived it this season chiefly for its most popular “étoiles,” the Bolshoi’s Svetlana Zakharova and Roberto Bolle. In them they certainly have two of the most gorgeous bodies in the ballet world. The performance could have been an ad for one of Milan’s fashion houses: Italian model falls in love with Russian model moonlighting as a courtesan. Add to that Cecil Beaton’s period costumes and spare set, and the ballet was a vision of surface elegance on opening night.

Emotion, however, proved to be the poor cousin. The days when Marguerite and Armand belonged solely to Fonteyn and Nureyev, then to Guillem, are certainly gone (3 other casts are scheduled in Milan), but there is something to be said for cherry-picking interpreters when the ballet distils Dumas’ novel to such an extent. It takes consummate dance actors to tell the story through pas de deux, from Marguerite and Armand’s first encounter to her death, in less than 40 minutes, and both Zakharova and Bolle would need partners who can force them out of their natural reserve.

Zakharova was making her debut as Marguerite, and while she has the beauty and the frailty, she is also slightly too perfect for her own good. Her coughs when the curtain opens are impossibly, almost ridiculously graceful; her arabesque line is a marvel, all the way through light, flowing arms with just the right curve at the elbow, and yet no character shines through early on in the ballet. On opening night, she only came into her own opposite Armand’s father: her despair as she stood still upstage had the right note of restraint, and in the last scenes, she built quietly on the music, letting her slender lines speak without losing sight of the character’s dignity.

Tall and handsome seem to be Roberto Bolle’s defining attributes, and on this occasion he didn’t deliver much else. He’s obviously a reliable partner, but his phrasing was otherwise off, with hops and wobbles throughout his opening variation. The audience in Milan didn’t seem to mind: the local star’s solo bow in front of the curtain (Zakharova wasn’t even afforded the chance) drew the loudest cheers of the evening.

Alexei Ratmansky’s Concerto DSCH had its premiere in New York in 2008, and it was about time we saw it in Europe. With new versions of Lost Illusions and Firebird, among others, Ratmansky has been hard at work with narrative lately, but the plotless one-act ballets he created for New York City Ballet are still among his very best works. The warmth and sense of community evident throughout Concerto DSCH are reminiscent of Russian Seasons, and the inventiveness of the choreography sweeps the audience along with masterly ease, one subtle change of mood, one quirky detail after another.

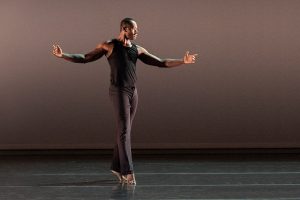

The first movement is a whirlwind of bravura choreography for both corps and soloists, with fiercely difficult Bolshoi-style turns and jumps and playful, off-balance musical accents in the best NYCB tradition. It would take more time for La Scala Ballet to master that style, and on opening night the dancing often looked blurry. Ratmansky’s affinity with Shostakovitch, already demonstrated in The Bright Stream, is obvious nonetheless: his ability to blend dance architecture on a grand scale with an abundance of human details for each role is a perfect match for the wit and occasional stridency of the composer’s first and last movements. It’s a wild emotional ride, and as soloists and corps groups in colour-coded costumes cross paths on stage in one effortless transition after another, the choreography’s accumulating layers beg for repeated viewings.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Ratmansky’s work may be the way he choreographs for women. They never come across as passive objects of beauty to be manipulated at will – even in the arms of a partner, they often define the lifts, striving to express themselves, radiating energy outwards. In Concerto DSCH, the sole woman in the trio of soloists is the men’s equal, performing the same explosive jumps or turns and occasionally partnering them. The lead woman, meanwhile, acts as a figurehead for the community. She leaves behind her heady pas de deux to join a group of corps dancers near the end of the second movement, and at several points the ensemble rallies around her in a tight circle. In the end ballet hierarchy is respected – we have principals, soloists, and a corps – but it isn’t modelled after a divine order or a caste system; the soloists belong to an imperfect community (Ratmansky plays with broken patterns throughout) and are singled out by it, seemingly for themselves.

European balletgoers will wonder how Concerto DSCH compares with Kenneth MacMillan’s 1966 Concerto, set to the same score, but the two works have little in common in their approach. Both choreographers imagine the central movement as a pas de deux with three couples appearing in the background, and yet the result is strikingly different in mood and choreography. Where MacMillan draws on the solemnity and sense of foreboding in Shostakovitch’s Piano Concerto No. 2, Ratmansky infuses its long, flowing phrases with human drama. The introduction, performed to an empty stage in Concerto, is filled out by the corps couples, and when the leads join them, they enter from the back, walking together. Their pas de deux is a pensive conversation with its own motifs: sinuous, singing phrases, low lifts, fluttering beats for Zakharova. In a nod to MacMillan, the 3 corps couples are in orange and fleetingly form a line at the back of the stage, but they soon break out in contrasting duos behind the leads – corps or not, they have relationships of their own to tend to.

It takes Ratmansky to make Zakharova look quirky, and she was at her least inaccessible, lyrical yet human, in the role created for Wendy Whelan. In the virtuoso pas de trois designed for NYCB powerhouses, Federico Fresi, a young corps de ballet dancer, was the standout, whipping off double tours en l’air and jumps with true Italian charm. Antonino Sutera held his own, and Alessandra Vassallo, another corps dancer, had all the velocity needed but not quite the upper body precision. At one hour and twenty minutes, this was a very short evening, and a third work would have been the opportunity to showcase more of the company’s own talent. Let’s hope Vaziev has some home-grown first casts in mind for the future, too.

This is a very interesting and thoughtful review. There is no doubt as the article underlines that dramatic ballets like “Marguerite and Armand” or “Manon” recquire consumate actor-dancers with personnality and style, able to convey meaning and emotion with their body and face language.

With regards to “Marguerite and Armand” this is more than obvious. Imagine a thirty minute ballet which tells the whole story of Marguerite Gautier and her doomed love afafir with Armand Duval. The lead female dancer has to convey an immense palette of emotions in a short period of time and in diversified contexts.

The ballet was written for Nureev and Fonteyn and it was not until Sylvie Guillem reprised the ballet that the audience was given a chance to be given a fresh look at it with an incomparable artist like Sylvie.

In the case of Fonteyn-Nureev you had the consumate dancers-actors and they also had the secret to make it work as a couple which is a key element to “Marguerite and Armand”.

Sylvie understood this supremely and she not only gave it a new life she also knew how to make it work with her partners like Nicolas Le Riche and Massimo Murru. The beauty, the emotion, the violence, the romanticism everything was there in addition to her superlative technique which always serves the character she is portraying.

In the case of dancers like Zakharova and Bolle you have dancers whose skills work fine for ballets like “La Bayadere” or “Swan lake” but quite simply fail to give someting moving in dramatic ballets like “Marguerite and Armand” and I fear as much for the upcoming Manon in the 2012-2013 La Scala season.

One also has the right to wonder and even be angry why didnt La Scala invite Sylvie Guillem this year to perform Marguerite and Armand opposite Murru as they reportedly have not done for their next Manon which is even more amazing and infuriating especially given Sylvie”s huge triump as Manon at La Scala in 2011.

Svetlana Zakharova: The Next Ballerina Of The Gods

by Dane Youssef

Zakharova herself certainly seems to be at the top of the world right now. The ballet world. And Roberto Bolle. Perhaps the only man alive right now fit to share the stage with her. Well, not counting the likes of Ethan Stiefel, the greatest American male ever to prance and Vladimir Malakhov (who’s currently the greatest Russian MALE dancer right now. Svetlana Zakharova and Roberto Bolle. Cappelle’s right Certainly some of the two most gorgeous bodies doing ballet.

Especially Zakharova.

Destined without question to be the next “Prima Ballerina Absolutta” and even likely to shine brighter than even Dame Margot Fonteyn or Alessandra Ferri.

She just seems to have every single asset a dancer of ballet needs. Extensions that just seem to go on forever and ever… Long, strong feet with those ludicrously high arches and insteps and a passion that seems to burn, burn, burn.

Everyone who’s had the good fortune to see her dance, ever balletomane… everyone period–calls her feet things like impossibly perfect, endlessly beautiful, made for ballet… and too Goddamned good to be true. Every by her peers born with similar advantages. Similar, but not quite as good. And while we seem to envy those who are just given all the advantages, all the natural gifts that evolution can possibly have to offer.

Some are blessed. Blessed to the point that it’s ridiculous. Blessed to the point that it’s true, life is especially unfair.

I’ve always said that the greatest ever to dance ballet, not just professionally but period, ever to associate with the art, ever to even place on a leotard, tights and toe shoes (aside from “Misha” Baryshnikov himself) was Natalia Makarova. She just had the body. She just had it. For ballet, she just naturally seemed like she was created in a laboratory–out of all the nessicary parts a woman would need for the practice of professional classical dance. I asked what I’m sure everyone who saw her dance did, “Will there ever be another–in this lifetime or any other?”

I always said fellow Russkie and “Prima Ballerina Absolutta” Natalia Makarova was the greatest in history ever to do ballet and I always wondered if there would ever be another. There is. Natalia seemed just born for it. So did Svetlana. God Help us all, they actually surpass the likes of Mikhail Baryshnikov and Alessandra Ferri as dancers. They are simply goddesses in their craft. And I actually believe Zakharova may surpass Makarova. I saw all your flick on Zakharova. Please… keep it going. Complete it. Like her own career in ballet and her life itself, it should keep going and not stop until she does.

–A Fellow Follower of the Faith of The Temple of Svetlana Zakharova, Dane Youssef

I agree with you Dane Youssef. Svetlana Zakharova is truly the greatest of them all. How can anyone has the perfect feet, body, technique, musicality, emotion and face combined? Others have one or two but not all. I am just thankful she is here in my lifetime.