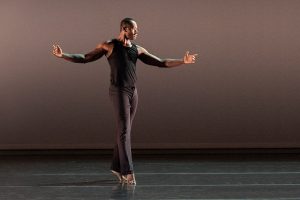

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

SPAC opening night 2012: Concerto Barocco, Kammermusik No. 2, Firebird, Symphony in C

Saratoga Springs, Performing Arts Center

10 July 2012

www.nycballet.com

spac.org

It’s always a pleasure to return to the great almost-outdoors of the Saratoga Performing Arts Center, still the summer home of the New York City Ballet, however abbreviated its visits may become (originally a month-long residency, now two weeks, and scheduled for only one next year). There’s something magical about watching the ballet in a deepening summer twilight, surrounded by sky and massive pines, and, if you’re lucky, Midsummer Night’s Dream with real fireflies. This year, alas, the company didn’t bring Midsummer, leaving us to make do, for climactic aptness, with In the Night against a backdrop of a real starry sky.

However gloomy the prospect of a week-long season next year, and perhaps none after that (with the usual accusations from ballet fans here that SPAC management is far happier to put lucrative rock concerts in the July dates freed up by the ballet’s ever-shrinking seasons), City Ballet put on a fine show Tuesday night, with an all-Balanchine program of mostly classics, mostly well-danced.

One could hardly go wrong starting such a program with City Ballet’s gold-standard curtain raiser, Concerto Barocco, and one hardly did, except for the debut of Savannah Lowery as the “second-fiddle,” one of the cascading failures set-off by the continued absence of the still-injured Sara Mearns, a far more appropriate choice to be paired with Teresa Reichlen. Although Reichlen and Lowery are of the same tall height, against the supple sapling of Reichlen’s physique, Lowery was a rough-hewn log, and, worse, danced that way. Athletic and unfettered by nuance, she’s been effective in all-out, aggressive works like Symphony in Three Movements, but with an epaulement best suited for protecting one’s quarterback from the odd defensive tackle, she’s lost in works requiring far less refinement than the sublime Barocco, however breathlessly it may sprint to its curtain.

Barocco’s eight corps girls are always among the company’s most senior and accomplished, as their part’s both a challenge and honor, and I’d gladly have taken any one of them over Lowery.

In the almost painfully exquisite adagio, Ask la Cour showed that, whatever one might think of his inconsistencies as a dancer, he’s a sturdy partner indeed, twining and cantilevering the willowy Reichlen with ease. The pair’s height made some signature moments quite breathtaking, as when he slid her arrow-straight body upstage, toeshoes first, then, with one hand, provided the resistance against which she opened into a deep attitude, as if he were planting a flag that unfurled in the breeze, or, more aptly, transformed into a billowing spinnaker. Touching her pointed foot to the stage between side-to-side lifts, La Cour made Edwin Denby’s famous “deliberate plunge into an open wound” beautifully manifest, if not, perhaps, as painful as that unforgettable simile.

I didn’t care much for Kammermusik No. 2 back at its birth in 1978. For all the rushing dynamism of its two lead couples—especially Karin von Aroldingen and Colleen Neary, with their flying ponytails—and the plastique fortifications of its eight-man corps (Barocco’s distaff cousins?), it seemed oddly episodic and devoid of argument, perhaps due to its score by Paul Hindemith for piano and orchestra, which manages to be simultaneously bright and turgid. With subsequent revivals over the years, I’ve appreciated more and more the breadth of its invention and eclecticism, and how, for all its sere neoclassical presentation, it’s almost a Balanchine scrapbook. In just a few beats of one of Neary’s solos, you can see, for instance, the on-the-heels shuffle from Apollo, and jazzy, finger-pointing pose right out of “Fascinatin’ Rhythm” from Who Cares?

But when Kammermusik began to seem more to me was as some sort of alternate-universe, inverted version of Stravinsky Violin Concerto. In the flexed-footed, folksy steps that abound throughout, it’s not hard to see the Russian folk dance idiom of the happy peasants of Violin Concerto’s perky final movement, although here spread like butter over all the work. Both ballets have two lead couples, but while in Violin Concerto they’re most notable in the adagios Balanchine made for each, Kammermusik’s most striking when the sexes are paired together, in a competitive duet for the men, and, in almost the ballet’s signature, with the two women leaping in unison about the stage, and the aforementioned aerial ponytails. And, of course, Hindemith’s lead instrument is the piano, not violin.

If it still doesn’t quite jell in my mind as presenting a unique neoclassical place such as the weird worlds of, say, Episodes or Agon, Kammermusik still entices. Rebecca Krohn, newly promoted to principal, was clean and precise, although with her usual wan presentation, and hardly a successor to the Amazonian Von Aroldingen. (I wanted to shout, “More Ponytail!” as if it would’ve made a difference.) Stafford was stronger and more musical in her solos, although the two seemed well-paired in romping about the stage in their simultaneous grand jetés. Jonathan Stafford partnered Krohn, and Jared Angle, Abi Stafford.

After the dreary bombast of Alexei Ratmansky’s recent Firebird for American Ballet Theatre, the Balanchine/Robbins version, with its blessedly shorter score (Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite), heavenly Chagall designs and the great Ashley Bouder in one of her first great roles, was a welcome palliative. I suppose there will come a time when Bouder no longer improves her roles whenever she returns to them, but it’s not now, and, hopefully, not for a long time to come. As wings, her rippling arms have passed into Makarova territory (I can’t think of higher praise), as beautifully evident in their desperate fluttering and pinioned stillness, as the Firebird vainly tries to escape Prince Ivan at the beginning of their adagio of mutual fascination. It was a delight to absorb Balanchine’s attention and attunement to niceties of Stravinsky’s to which Ratmansky was (uncharacteristically) deaf or indifferent.

As Ivan, Justin Peck was at least as flexible, and certainly no more wooden, than his bow. Perhaps he’ll join the departed Benjamin Millepied in being, as a dancer, a great choreographer. Gwyneth Muller was a delightful bride, leading her ensemble of twelve captive maidens, and, yes, I was happy to see them in proper kokoshniki, instead of Elsa Lanchester fright wigs. I was even happy to see Jerome Robbins’ ridiculous monsters, especially as they’d soon lead to Bouder’s return to rescue Ivan, and the heart-stopping manége of ever-faster grande jetés (with no intervening glissades or steps) with which she circles the stage before her flying exit. The Firebird’s berceuse is as heartbreaking as ever, and the final wedding scene, flags and the princesse’s scarlet dress flying, as glorious.

This was my first look at the new Marc Happel costumes for Symphony in C, and I fell in love with them at first sight, or rather First Movement, because the romance was that short-lived. The new, whiter women’s costumes boast their celebrated sprays of Swarovski crystals. Flatter, bigger tutus mounted higher on the hips make for a sleeker and traditionally classical, even Russian, silhouette, emphasizing the unbroken length of the women’s legs. I loved the crystals rainbow-hued sparkle, which gave a delightful little boost to the dancers’ every movement (the mens’ black costumes are similarly adorned), like the fizz of bubbles in champagne, and seemed an apt, if oblique reference to the ballet’s beginning as Le Palais de Cristal.

Alas, I soon noticed that higher, flatter tutus not only showed more leg, but more panty as well, and it seemed that with the dancers’ every step and jump, we’d be flashed, and not just by those crystals. It’s ironic that we can see dancers as close to naked as makes no difference in unitards or less without the slight flinch we can get at a crotch or derriere peeking (or, in this case, shouting “Hello, sailor!”) out from under a bouncing, flipping tutu. It’s just distracting, and I cringe knowing that for the rest of my life, Symphony in C and “gratuitous crotch shots” will be inextricably linked in my mind. (I remember the costumes for Kaleidoscope, Peter Quanz’ 2006 Balanchine pastiche for ABT, suffered from similarly unflattering tutus.)

The whole point of a tutu, especially a “pancake” classical one, was to maintain the fiction that, somehow, the ballerinas one would see exposing their legs for all the world to see were doing nothing of the kind, by maintaining a metaphorical fig leaf between the chaste female artiste above, and those problematic limbs, not to mention other nether regions, below. When they’re so flat and high as to expose those naughty bits more often than not, why bother with them at all?

Worse, those crystals that glittered so delightfully in the allegro First Movement, became a visually noisy distraction in the adagio Second. It was particularly difficult to admire Maria Kowroski’s line and her slow, deliberate pacing back into the adagio’s final poses, with what appeared to be the Fourth of July going off in her décolletage. We’re watching one of the most exquisite adagios in all of ballet, and we must contend with the snap-crackle-pop of these little flashbulbs randomly going off with the dancers’ every breath?

I suppose I will learn to mentally filter out these flashes, both literal and colloquial, and get back to the business of enjoying Bizet, but I wish I didn’t have to expend the mental energy and, as any Photoshop maven will tell you, filters are inherently destructive.

Oh, the dancing? For the most part, glorious. Megan Fairchild and Andrew Veyette welcomed us on board in the allegro First Movement. Sterling Hyltin and Joaquin de Luz flew as brilliantly as you’d expect in the vivace Third Movement, De Luz’ easy overhead lifts of Hyltin, who must be at least his height, were the thrilling surprise. And Tiler Peck, the company’s best turner, seemed hardly to need Adrian Danchig-Waring’s support in the turningest, Fourth Movement. Maria Kowroski seemed to be having one of those unfortunate nights when nothing would go right. After a near-disastrous case of wobbly hips in the balance with her leg in high second, that just precedes the famous head-to-the-knee penchées, and her last-minute rescue by Tyler Angle, she seemed to retreat mentally into survival mode, simply trying to get through the ballet without any more near disasters. Her many turns in the Fourth Movement were particularly depressing. I’d like to think this outing was a fluke, and she’ll be back to her usual astonishing self. Unlike a local newspaper critic, I could find no fault in the tempi of Clotilde Otranto’s conducting, which was, as is her wont, bright and alacritous.

You must be logged in to post a comment.