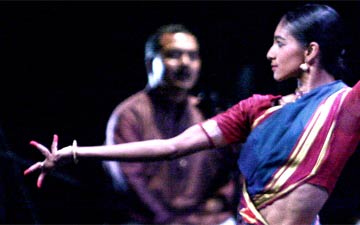

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for larger version)

Shantala Shivalingappa, or When Beauty is Not Enough

Shantala Shivalingappa

Namasya: Ibuki, Solo, Shift, Smarana

New York, Joyce Theater

27 June 2012

www.shantalashivalingappa.com

Disappointment is an inevitable part of theatre-going – I mean, how often do performances live up to our expectations? – but it is especially hard to swallow when it comes at the hands of one of the artists we most admire. It’s not the end of the world, but it’s a shame.

So it was with Shantala Shivalingappa’s recent solo evening at the Joyce. She has danced in New York before, both with the Pina Bausch troupe and in solo performances of her own, the latter of which have always been evenings of kuchipudi, a classical Indian dance form of which she is one of the world’s finest interpreters. In her evening-length program last fall, “Swayambhu,” she spun vivid stories with her body, the most memorable of which depicted the Goddess Padmavati dreaming of a quarrel with her husband, Lord Venkateshwara. She prepared the bed, she lay down on it – is there anything more beautiful than Shivalingappa in repose? – she twitched in her sleep, she rose in anger, and then, realizing it was all a dream, she smiled and all was well with the world.

But this time Shivalingappa chose to present the other side of her artistic life in which she has collaborated with a series of contemporary directors and choreographers including Peter Brook, Pina Bausch, and now Ushio Amagatsu (founder of the Butoh dance group, Sankai Juku). This wide range reflects her upbringing: Shivalingappa was born in Chennai and brought up in Paris. Her mother, Savitry Nair, is a well-known classical Indian dancer and teacher, and was a close friend of Maurice Béjart, as she recently told Gia Kourlas (interview link). Both Shivalingappa and her mother have taught at Béjart’s dance school (Rudra) in Lausanne. The exposure to contemporary dance is as much a part of her as her devotion to kuchipudi.

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for larger version)

More recently, she danced with Pina Bausch’s company, most notably in “Nefès” and “Bamboo Blues.” Shivalingappa has said that Bausch introduced her to a more spontaneous, freer way of moving. It’s clear, too, what Bausch saw in Shivalingappa: clarity, lightness, beauty of gesture, the joy and pleasure of movement, a quiet, unforced femininity and charm. Her solo in “Nefès” was so beautiful, she did it twice. Out of this partnership came the Bausch solo Shivalingappa brought to the Joyce, titled, simply “Solo.” This was the cornerstone of the program. The other works were by Ushio Amagatsu, Shivalingappa and her mother, Savitry Nair. All were composed in a kind of loose contemporary vein, with splashes of South-Asian gesture.

None was remotely as complex or revelatory as her Kuchipudi choreographies have been, nor did the evening include live music, usually a crucial counterpoint to her dancing. (Have I mentioned she is one of the most musical dancers I have seen in any form?) Bausch’s musical selection was the most appealing of the evening: a laid-back bossa-nova-like ballad by Ferran Savall (son of Jordi Savall) entitled “Paris.” It sounded like something one might hear late at night at a terrace bar near the beach in the South of France in July. In other words, like blissed-out, carefree, slightly weary pleasure. The dance had the same quality: lilting and sensual, with just a touch of melancholy. Shivalingappa emerged from the wings in one of Bausch’s signature floor-length silk dresses (black) and spread her legs in a wide squat, swaying slightly and rippling one arm like a vine in the warm summer breeze. Her face expressed the memory of a private pleasure. With precise movements of the arms, hands and fingers, she seemed to shape the air around her, then caressed her cheek and hair. A beautiful woman enjoying her beauty. In another sequence she cycled through a series of South-Asian hand gestures, fingers splayed, now a peacock head, now a flower, like small offerings. At her best, Bausch has a way of tapping into subterranean sensations, provoking a kind of reverie; here, Shivalingappa allowed us into her daydream.

But it wasn’t enough to sustain the evening. The Amagatsu began well enough, with one of Shivalingappa’s elegant reclining poses, one leg bent in a graceful, sharp angle to the floor. But there were not many ideas, and what few there were were overwhelmed by the gratingly new-agey music by Yoichiro Yoshikawa. (The Joyce’s sound system did her no favors.) Then came the first of two overly long, artfully filmed video sequences depicting Shivalingappa in kuchipudi poses or dancing with her reflection in water; one imagines they were conceived in order to allow the dancer time to change (and rest) between one piece and the next. But they bogged down the evening even further.

© Laurent Philippe. (Click image for larger version)

It wasn’t until the final moments that things once again regained focus, in Savitry Nair’s “Smarana.” As the dance began, Shivalingappa sat with her back to the audience. She began to sway, slowly pulling up her torso like a snake uncoiling from a basket, finishing with a slight side-to-side figure of the head. Once again, it was the absolute clarity of her movements that struck one the most. For most of the dance, her back was turned as she revealed isolated details, a shimmering of the fingers, an undulation of the arms. The very stillness was stirring, almost meditative. Then, the final coup de théâtre: kneeling, with her back to the audience, she slowly raised her arms and formed two peacock heads with her fingers, then, almost imperceptibly, drew them closer together until the two shapes overlapped and became one. Opening her fingers, the hands became a lotus flower floating overhead. For a moment, the sense of wonder returned, and then it was over.

[Link to Pina Bausch solo here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSYCSxRvT0I]

I’ve only been able to see Shantala once. I am somewhat familiar with Kuchipudi, more so with Bharata Natyam, and was blown away by her beauty and her understanding of tradition.

Over the years, seeing other traditional Indian dancers who want to explore — and create — a connection with Western dance forms, I have repeatedly gotten the sense that these dancers (through no fault of their own) are missing the understanding that comes from repeated exposure to the medium that would give an understanding of what is over-used, what is original, what is a little worn-out and what is exceptionally original. On the other side of that same coin, in my Western dance-going experience I have seen many versions and interpretations of the same ballet, the same solo, the same character, etc., so that I can separately judge the elements and quality of what I am seeing.

On the other hand, though I have seen many performers and several interpretations of the many separate elements of Bharata Natyam programs, I have not developed my judgement so that I can always see the difference between is a poor interpretation or a sloppy rendition. They just haven’t seen as many really bad copies/versions of a Martha Graham dance as I have.

I feel that the reason many excellent performers of Asian dance who attempt Western performance forms do not succeed is that they are missing the nearly instinctive judgement that comes from a lifetime of exposure and comparisons. Shantala may be one of the few performers who do not have that “excuse,” but it shows me how important it is.

Thank you so much for your detailed comment.

Solo shows are tricky. I think it’s very difficult for artists working in one genre to develop an equally sophisticated taste in other genres. Witness Diana Vishneva’s one-woman show Beauty in Motion. But I respect the desire to try new things. Especially when an artist possesses such universal dance values–clarity, speed, musicality, beauty of gesture–as Shivalingappa. It is inevitable that there will be successes and failures. In this case, though, it was the lack of ambition that I found disappointing. Her kuchipudi programs are riveting, so we expect so much from every appearance onstage….