© Dancetime Publications. (Click image for larger version)

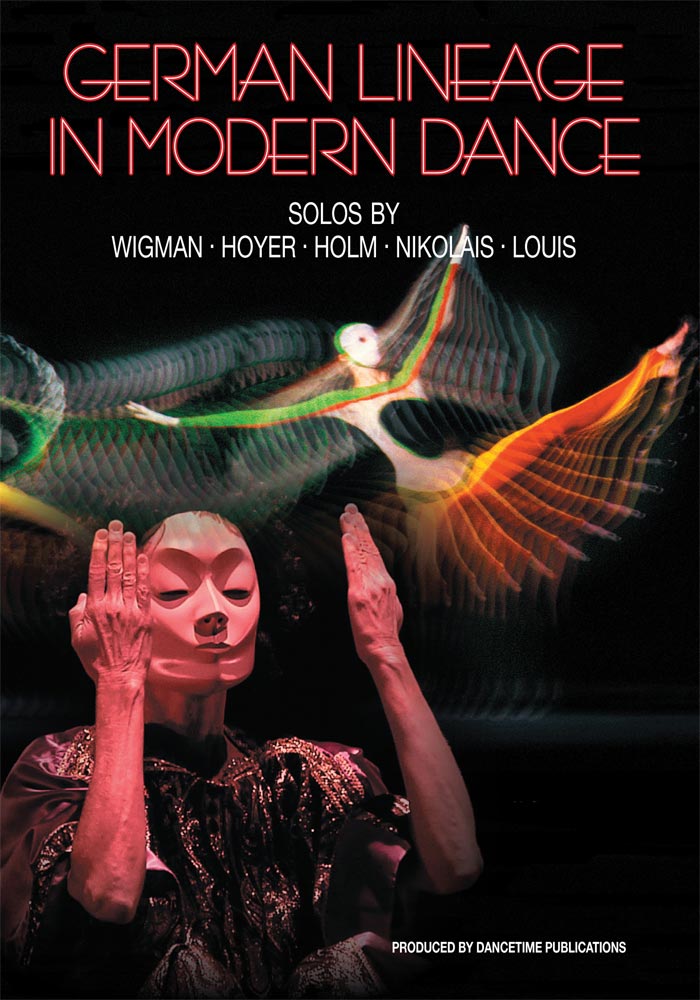

DVD: German Lineage in Modern Dance

Presented by Dr Betsy Fisher

Running time: 58 minutes

Price: $49.95 by mail-order from the publishers

Dancetime Publications

German Expressionist Dance (or Ausdruckstanz) took shape after the First World War and had effectively run its course in Germany by the time that the Nazis took their iron grip on power. Yet, more than 70 years later, many of today’s leading European choreographers continue to keep the legacy of Ausdruckstanz very much alive in their work. Mats Ek, Angelin Preljocaj and Sasha Waltz are just three of today’s leading choreographers who can claim a direct line back to the Expressionism of Mary Wigman and her successors.

This DVD specifically traces modern dance’s “family tree” in the lineage from German expressionism through to American abstraction. The hour-long film is a tour de force by former dancer, now dance academic, Dr Betsy Fisher, who analyses the handing of this legacy across five influential choreographers, beginning – of course – with Wigman herself. Fisher dances extracts of their work and narrates a series of tightly-written documentary vignettes between the danced sections, each effectively illustrated by original photographs of the period. As she says in her concluding summary, several choreographers could have been used to trace the migration of these ideas from Germany to America but she selected Wigman, Dore Hoyer, Hanya Holm, Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis. Their interlinked stories provide a fascinating four degrees of separation to show how Wigman’s influence came to be felt across the continents.

Alongside her teacher, Rudolf von Laban, Mary Wigman (1886-1973) was the leading luminary of German expressionism. Her dances were without plot and often performed without music as she sought to portray universal truths through movement alone. The link to the supernatural in Wigman’s work is illustrated through her most famous piece, Witch Dance (or Hexentanz), originally made in 1914 and reprised 12 years later. Most of the original work is lost. Only a few photographs of the 1914 iteration survived and the score has also disappeared. Just the opening two minutes of Wigman dancing the 1926 version still exists on film.

© Tom Caravaglia. (Click image for larger version)

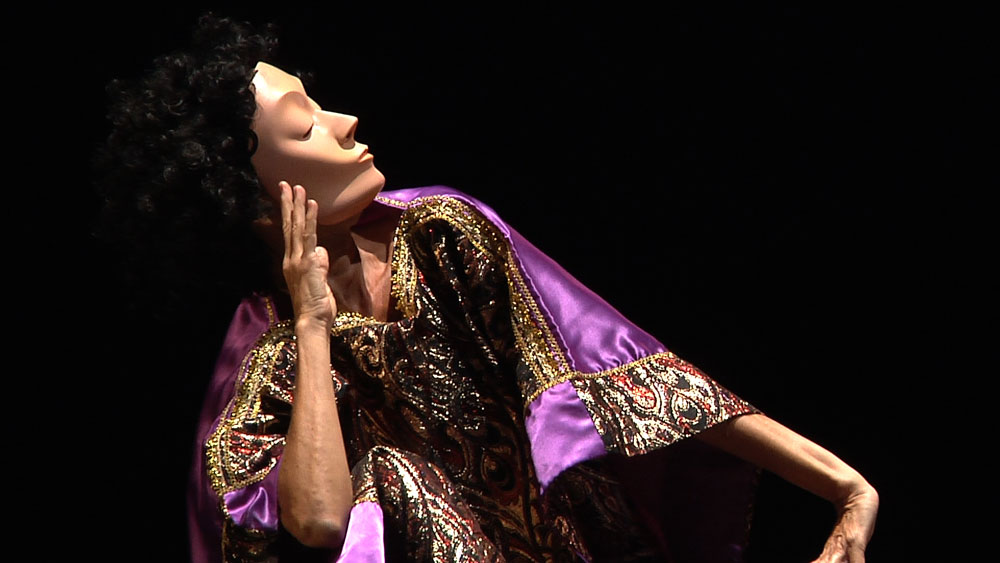

Wigman wrote that “art is not a copy but an invention” and Fisher has used all available resources to attempt to understand the basis of Wigman’s Hexentanz so that she is able to perform her own interpretation of it. She describes it as the “discovery of the dancer’s own witch within”. Michael Harada has made for her a copy of the remarkable Makito mask worn by Wigman with its curly dark hair, high cheekbones, arched eyebrows, pursed lips, sharp, piercing nose and pointed chin. From photographs of the original, this replica mask seems remarkably similar and Fisher dances this most iconic piece with a controlled and arresting intensity.

Fisher does Wigman the honour of performing an extract from a second of her works – Schwingende Landschaft (Swinging Landscapes), which she made in 1929. This was a cycle of 7 dances, of which only 3 remain and exhibits a very different domain, which Wigman described as a “colourful flower bouquet”. Fisher dances a minute’s excerpt from Seraphisches Lied (Seraphic Song) like a monk at prayer; another from Pastorale, her hands and wrists floating like a butterfly on the breeze; and finally in the joyful Sommerlicher Tanz (The Dance of Summer). I had only really previously thought of Wigman in the context of the darker Hexentanz side of her expressionism and this lighter dance, like a frolic in a meadow, was an eye-opener.

Fisher describes Dore Hoyer (1911-1967) as a “critical and exacting personality” known for the power of her “commanding performances”. Hoyer danced with Wigman briefly in 1935/6 and returned to perform the role of The Chosen One in Wigman’s Rite of Spring in 1957. Her own choreographic career spanned the years from 1933 to 1967 with her most acclaimed work being Affectos Humanos (1962).

This work blends dance expressionism and abstraction in a suite of 5 solos with each section inspired by a different emotion: vanity, greed, hate, fear and love. Each emotion is revealed through vivid movement and the precision of the performer’s exact placement in the stage space. Fisher says in her narration, “when Hoyer uses stillness the space is thick with tension, like a cat silently waiting to attack its prey”.

© Dancetime Publications. (Click image for larger version)

Directed by Hoyer’s former associate, Waltraud Luley, Fisher performs the solo for Fear, with her knees knocking together weakly while her arms reach high with one last burst of energy. The dancer appears to be in a losing battle with forces of external energy that pull her in multiple directions. Hoyer chose Love for the final section, which is the second solo performed here by Fisher. In coaching Fisher for these solos, Luley said that Hoyer’s movements must be “precise, nuanced and deep”. What really struck me about her work was how dance that appears to be so improvised is exactly choreographed in such fine detail.

Hoyer had a troubled life. Her tours to South America were extremely successful, especially in Argentina where she was dubbed La Davina but she was often unemployed at home in Germany, where Fisher says she became regarded “as a living relic of the German Expressionist tradition”. Hoyer never conformed to the cultural climate of post WW2 Germany. She felt undervalued and artistically misunderstood and she killed herself on New Year’s Eve, 1967. Speaking at her funeral, Wigman said “the last word about you, the word of recognition that bestows upon you the rank you have merited in the history of European dance art has yet to be spoken”.

Hanya Holm (1893 -1992) was a direct protégé of Wigman. She danced in her company and taught at her school. Holm was also the first – and the main – dance export from Germany to the USA. Wigman had taken US audiences by storm through her 1930s tours, being heralded as the “high priestess of the dance”. With her mentor’s support and the financial backing of US entrepreneurial promoter Sol Hurok, Holm opened the New York Wigman School of the Dance in 1931, soon afterwards adding a touring company.

Living to the age of 99, Holm became a major force in the genesis of American modern dance and along the way, as an extremely influential dance teacher, she “adapted Wigman’s expressive individualism to a more American movement sensibility”, says Fisher. Holm believed that “dance technique is not a specific style but a way of thinking about movement” and that “technique should be used in the service of creativity and not the other way around”.

© Tom Caravaglia. (Click image for larger version)

Holm taught at many other schools including the Juilliard School and the Bennington School of the Dance. For 43 successive summers, she also taught at Colorado College, which is where she made Homage to Mahler in 1976. Her Assistant in making that choreography was Claudia Gitelman who was the original soloist and it is Gitelman that coached Betsy Fisher to perform the solo in this DVD.

The deep expression of grief in Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children, based on the poems of Friedrich Rückert) motivated Holm’s solo, which Fisher says must be performed as “if the air was dense, giving anguish a textural and spatial expression”. It is, continues Fisher, the “ultimate sadness – a distillation of a subject to its essence. Holm reaches through the tragic narrative to articulate its deepest meaning in motion”. The simple clarity of this expression, danced here so fluently by Fisher, is transcendent and it reveals Holm’s expressionist roots back to Wigman.

The link to Alwin Nikolais (1910 – 1993) comes via Holm’s teaching at The Bennington School of the Dance between 1934 and 1939 where Nikolais was her student. His primary interest was abstraction. Nikolais believed that the “personality and ego of the performer should be left outside the studio”. He felt that his dancers should “move with an inner pressure that seared movement onto space”.

Fisher says that Nikolais believed that “the unique character of a dance is that motion itself is the end; the reason is within it rather than beyond it. The dance accomplishes itself”. Nikolais was both disciplined and extravagant and these opposite qualities were equally evident in his choreography. He pioneered new lighting techniques, using side lighting and projections onto the torsos of his dancers and he often composed his own music employing looping and over-dubbing on synthesisers. The score for the excerpt from Tribe (1975) danced on this DVD by Fisher was apparently composed on the second Moog synthesiser ever built.

© Tom Caravaglia. (Click image for larger version)

Alwin Nikolais had a professional and personal partnership with Murray Louis (b.1926) that lasted from 1946 until the former’s death in 1993. Together, they built an empire in the dance world from their base in New York. Louis’ work could be funny, mercurial and abstract. His dancers were characterised by their quick, light attack and he said that the dancers should be “equal partners with the music”.

Fisher needed no guidance for the excerpt that she dances from Figura (1978) since she danced it herself as a member of the Murray Louis Company and Louis himself acted as an artistic adviser for the DVD. Danced to La Comparsa by Ernesto Lecuona (performed on the piano by Grant Mack) it shows many similarities with the work of Wigman and Hoyer, particularly in the use of hands and arms and robustly underlines the thesis that Louis is a third-generation inheritor of Wigman.

This is not a DVD for casual enjoyment but it is a must-buy for anyone enthused by dance tradition and culture, students and teachers of contemporary dance and anyone with a strong academic interest in how modern dance developed across continents in the twentieth century. I’m glad to have it in my collection and highly recommend it to others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.