© MM Kane Kahiko. (Click image for larger version)

Into the Mix

Fall For Dance Festival – Program IV

Shantala Shivalingappa (Shiva Ganga),

Pacific Northwest Ballet (pas de deux from Carousel),

Jodi Melnick (Solo, (Re)Deluxe Version),

Ka Leo O Laka I K Hikina O Ka La (Hula Kane: The Ancient Art of Hawaiian Male Dance)

New York, City Canter

4 October 2012

nycitycenter.org

Every Fall For Dance program is a bit of a pot luck, which is part of the festival’s charm. This year it has been expanded to twelve of performances (each costing $15, up from $10 last year). As usual the fortnight covers a relatively wide assortment of styles – though it tends to stay away from both the most experimental and the most commercial extremes. An evening might contain a ballet company, a tap dancer, a national dance form of some sort and maybe something a little more conceptual. So far this year we’ve seen the Moiseyev Dance Company from Russia, Jared Grimes, Martha Graham, a company of hula dancers from Hawaii, and students from the Juilliard Dance program in a work (by Pam Tanowitz) reminiscent of Merce Cunningham. The programs seem more balanced than in other years, which is good in a way, but also less adventurous.

There’s usually at least one number on each program that most everyone will enjoy, a crowd pleaser, at the end. (And this is not a bad thing, I might add.) A few nights ago (Oct. 2-3) this slot was assigned to the Moiseyev Dance Company, a storied Russian troupe, who performed a suite of stylized folk dances drawn from the various corners of the former Soviet Union. Tartar, gypsy, Moldavian, and Kalmyk dances, all spectacularly arranged with precision and wit by Igor Moiseyev, the folklorist and choreographer who created the troupe back in the 1930s. (Moiseyev, who died in 2007, at the ripe old age of 101, has influenced generations of choreographers, including Alexei Ratmansky. Just look at Ratmansky’s Cossack dance in The Bright Stream.) The Moiseyev dancers, all ballet-trained, were spectacular, high-jumping, rubber-ankled, steely-thighed, quick as lightning. It was the kind of dancing that made you want to get out of your seat and cheer, or curse your parents for not forcing you to work harder in dance class as a child. In teh video above they are, doing the Kalmyk Dance, a dance from the steppes near the Caspian Sea – Note the dynamic changes and sudden, tension-building pauses. Even on video they’re thrilling.

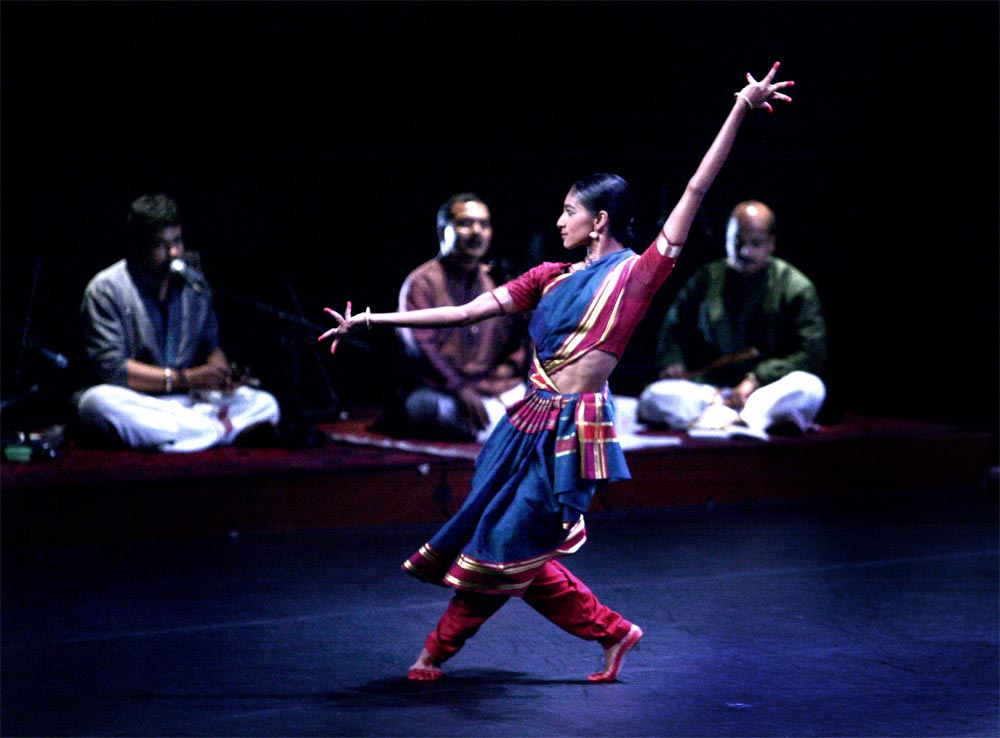

© C. P. Satyajit. (Click image for larger version)

The fourth program of Fall For Dance, (Oct. 4-6) began with a solo by the Madras-born kuchipudi, dancer Shantala Shivalingappa, with her ensemble of musicians (singers, drums, cymbals, flute, drone). She offered a condensed version of her evening-length work, Shiva Ganga, an exploration of the male and female aspects of kuchipudi technique as embodied by the figures of Shiva and Ganga, Lord of Dance and goddess of the sacred river Ganges. (The full work was performed at Jacob’s Pillow in 2010 and will be reprised at the Ringling Festival in Sarasota, Florida next week. My advice is to buy a plane ticket.) One needn’t know anything about Indian dance (or Hindu mythology) to see that Shivalingappa is an astounding artist. Beautifully proportioned, with long, slender arms, a delicate torso, and an elegant profile, she creates graceful silhouettes that are always perfectly legible, three-dimensional, pure. Her jumps are astonishingly light, as well as effortless. And she is certainly one of the most musical dancers I have ever seen, in any form. Not only are the movements of her body indistinguishable from the music, but she can switch from slow to fast, muscular to fluid, potent to sensual in an instant, with total ease. At Fall for Dance, after several manèges of turns on her knees in the waning light, Shivalingappa’s solo ended with the dancer bent forward, near the floor, her arms rippling. The image was of a body metamorphosing into the river Ganges, the embodiment of grace, beauty, fluidity, flowing in the near darkness. Her body had become a landscape. It was an image of stunning beauty.

© Angela Sterling. (Click image for larger version)

Another dancer with glorious lines, Carla Körbes, returned to New York for the festival, as part of an advance party from Pacific Northwest Ballet (the full company will perform in New York in February). It was a homecoming of sorts, not just for Körbes – who danced with New York City Ballet from 2000-2005 – but also for her partner, Seth Orza (a former NYCB soloist) and for their boss, Peter Boal, a star with the company in the eighties and nineties (he joined the day after Balanchine died). At City Center, Körbes and Orza danced a pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s moody, semi-abstract ballet on themes from Carousel (the Richard Rodgers musical), originally made for NYCB. This was back when Wheeldon was the house choreographer. (Ah, the good old days.) I remember the ballet well – it had a dark quality that one could not quite put one’s finger on. It was the first work in which I remember thinking that Tiler Peck was rather more than a perky technician. The opening of the pas de deux makes one anxious: there is something illicit about the relationship between the man and woman, who seems younger and dangerously vulnerable. One fears for her. The man calls her back several times, as if putting a spell on her; then leaves her standing awkwardly alone onstage. But rather quickly it becomes one of those rapturous pas de deux in which the woman runs into the man’s arms and the man swoops her up in ecstatic poses. There is a back-lift reminiscent of the “swimming” passage in Apollo, followed by a series of swan-like lifts as passionate as anything in Manon. Orza was handsome, but a little opaque; he’s not a particularly expressive dancer. Körbes was supple and quietly luminous, her pony-tail swinging behind her as she waltzed and swooned in Orza’s arms. It was a lovely interlude, but stripped of context and accompanied by only a pianist (the excellent Alan Moverman) it didn’t quite have the impact I remembered.

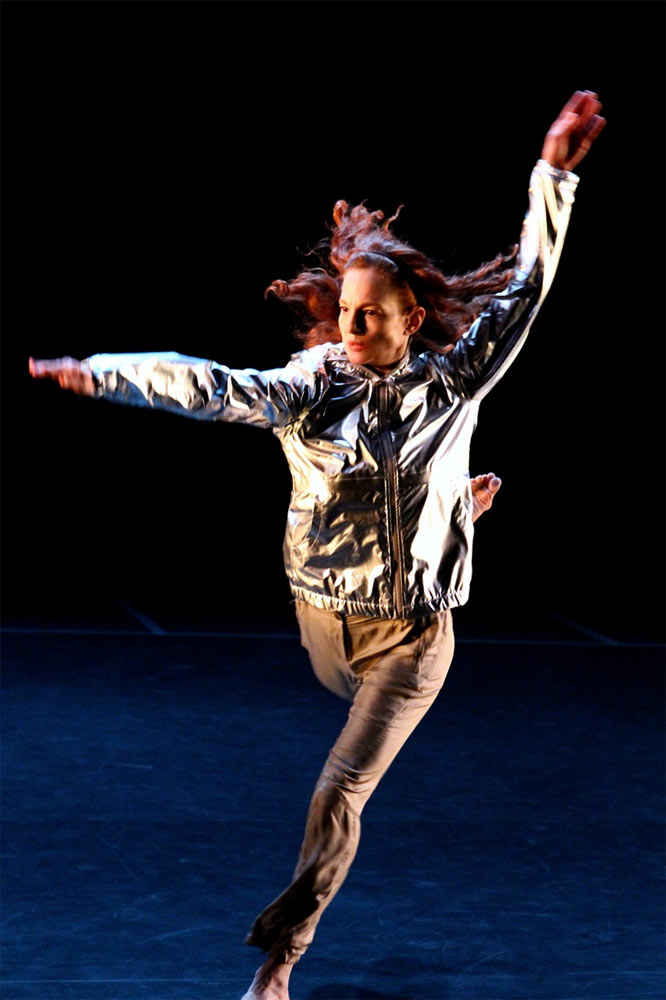

© Alex Escalante. (Click image for larger version)

Some varieties of dance fare better than others in this type of festival atmosphere. Jodi Melnick’s Solo, (Re)Deluxe Version was a perfect example of what doesn’t really work. Which is not to say that Melnick, a former Twyla Tharp dancer, is not an exceptional performer. She has that ineffable quality, the ability to make you want to look at her, no matter what she does. Add to that a kind of profound New York cool. Like so many New York artists from a previous generation (just think of Warhol, Trisha Brown, and Lou Reed), she’s imperturbable, nonchalant, deeply self-assured. The look of the solo (which later became a quartet) is very Trisha Brown: loosey-goosey, casual, and built mainly from deceptively simple articulations of the body combined with a good dose of attitude. The joints hinge, the body’s weight sinks into one hip, and then the other, a knee bends, an arm swings and hooks over the head. There is a quiet pleasure and freedom in this sort of dance – it’s an exploration of the body, of space, of the imagination. In the hands of a truly interesting dancer – like Melnick – it becomes a conversation. Subtle variations in tempo and texture – staccato to legato, allegro to andante – break up the pace. Melnick was joined on stage by a rock trio (loud but undeniably invigorating) and later by three other dancers, two men and a woman (Hristoula Harakas, Jon Kinzel and Kayvon Pourazar). Melnick wandered in and out of interactions with each of them; duets and trios formed; people sauntered on and off stage. Each dancer had his or her own quality: Harakas, a lush sensuality, Pourazar, his usual wounded intensity, Kinzel, a kind of dopey charm. Eventually the back curtain went up, revealing the theatre’s raw structure. The dancers rested and pushed against the back wall. Their relaxed affect and clear affection for each other springs from days, weeks, years of working in the studio together. They are all part of the same scene. But I had the sad thought that all this coolness and deconstruction felt tired, spent: this mental and physical territory has been mined and considered before. And in a large, formal setting like Fall For Dance, its quiet poetry loses its charm.

All thoughts of quiet introspection were swept aside by the final number, however, a hula ensemble from Hawaii called Ka Leo O Laka I Ka Hikina O Ka Lā performing a world première, Hula Kāne: The Ancient Art of Hawaiian Male Dance. We don’t see much hula in New York, but I’ve read that troupes like this one are the offspring of a hula revival that began in the seventies in an effort to recapture, or at least simulate, the original sacred intentions of hula: no more ukuleles and pretty girls in grass skirts. The dancers were all men, and what men! With the exception of one or two, they were more like heroes of myth: exceptionally tall, with glistening skin, broad swimmer’s torsos, long legs, narrow waists, six-packs and more muscles than one could count. I know all this, because they strode out in tiny green speedo-like costumes (and wreaths of leaves around their necks and heads), permitting full exposure; they later added a second layer of fabric, folded about their waists like an elaborate bow. The women’s complement sat behind, well covered, chanting and beating rhythms with gourd-like instruments. A lead vocalist (Kumu Jula Kaleo Trinidad, the leader of the troupe) presided from a platform at the rear of the stage, singing out in a strong, lilting voice. The elements of the dance were clearly derived from some sort of devotion – the men chanted, raised their arms to the heavens, or squatted down with their legs in a wide stance, arms drumming out rhythms on chest and thighs. One section seemed to be a stylization of combat, with sticks held above the head like lances, or plunged down as if to spear a fish. And, to the crowd’s delight, the men swiveled and swayed their hips with a blithe sensuality that elicited whoops and cheers. Was this the right reaction? As in samba, it seems, the sublimation of sex is part of the point. And yet the dancers’ demeanor was serious, even somber. The dancers’ expressions said one thing, their hips and gym-sculpted bodies another. It goes without saying that they were the hit of the evening, especially with the ladies. Just another night at Fall For Dance.

[…] Ballet, Jodi Melnick and friends, and an all-male hula ensemble from Hawaii. I wrote about it here, for DanceTabs. And here is a short excerpt, from my description of Shantala Shivalingappa’s […]

Thanks for the wonderful report. I agree with you about both programs, and the highlights and lowlights. I was a bit surprised to see all the awards that Jodi Melnick had garnered, because her work simply did not make an impression in that place or space. Perhaps somewhere else I will get a better feeling for her dances.

Re the hula: I’m always amused by Americans’ reaction to men’s moving hips. It’s made into such a huge thing because it’s so rare and generally considered “unmasculine” here.. (At least for white Americans.) I thought your comparison to samba was interesting, but I have two provisos on that.The first is that I believe the dances we saw here had a spiritual dimension, while samba is quite definitely secular in nature. (Though always celebratory, too.) I also wonder about “sublimation of sexuality” in samba. In its origins, it was more like a prelude to, rather than sublimation of. It’s flirtatious–hence the fact that it would rarely be segregated by gender.

In any case, I did very much enjoy the hula and the rare opportunity to see beautiful men in a state of near undress while the women drummers were fully clothes! More than the hips, that was the real switch-out.

Again, I very much enjoyed your commentary!

I too see a sacred element in the hula, as i pointed out, which made the whooping all the more uncomfortable-making, very hubba hubba! Though with the green thongs and glistening pectoral muscles—certainly the result of more than dance class!—it did seem to be part of the point. And there is certainly something unexpected about seeing men move in this way; more than feminine, I think it looks very naked.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment…

[…] For Dance, she performed a shortened version of her evening-length solo Shiva Ganga. As I wrote in DanceTabs, “she is one of the most musical dancers I have ever seen, in any form. Not only are the […]