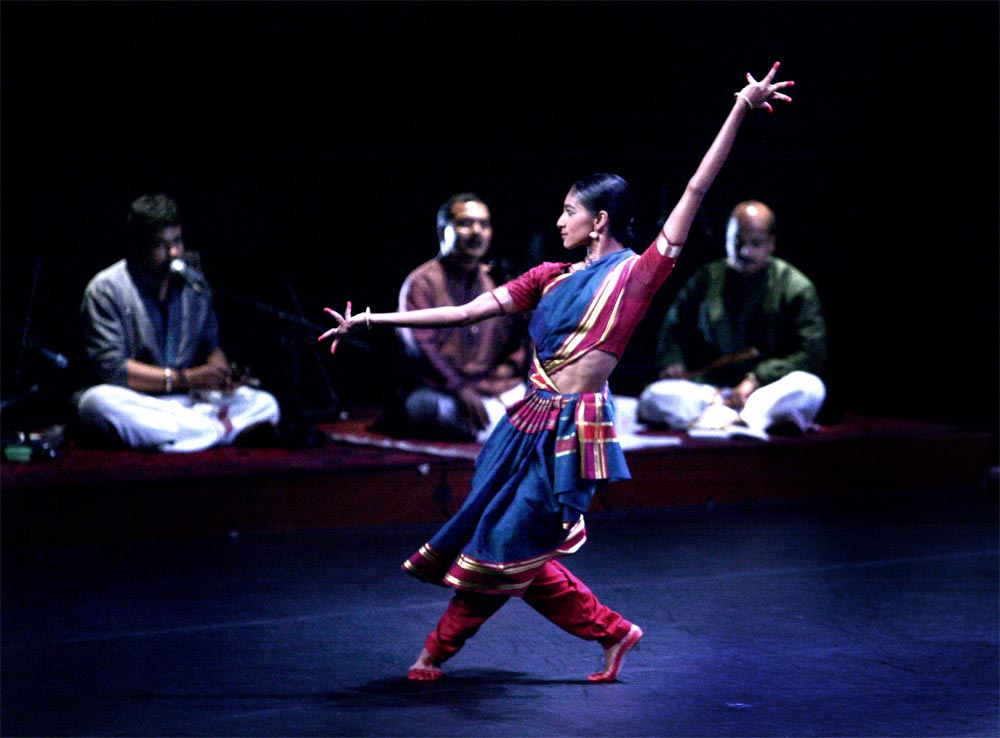

© Hector Perez. (Click image for larger version)

www.shantalashivalingappa.com

www.ringlingartsfestival.org

DanceTabs tag for Shantala Shivalingappa

Opening the Door

Shantala Shivalingappa is a young Kuchipudi dancer brought up in Paris, the daughter of the Bharata Natyam dancer and teacher, Savitry Nair. She first caught my eye at the 2007 Fall For Dance festival, where she danced Varnam, a Kuchipudi solo. I was immediately struck by her musicality, the power and precision of her footwork, and the absolute clarity of her movements. And to the grace of her upper body and a jump that seems to comes out of nowhere, light and airy as a cat’s. Since then she has performed in New York and at Jacob’s Pillow several times, both in her own solo Kuchipudi evenings (Swayambhu, Shiva Ganga) and with Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal, which she joined in 1998. Her mother exposed her to contemporary theatre and dance at a young age, and she has explored it more and more over the years, working with Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Peter Brook, and Ushio Amagatsu, among others. But it is clear she had a particular connection with Bausch. Shivalingappa lit up the stage in Bausch’s Nefès and Bamboo Blues, both of which were performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In Nefès, she gave her an Indian-flavored solo, which Shivalingappa performed with a half-smile on her face, as one of the other dancers (a man) stood and watched, entranced. Then another dancer came on (another man), and Bausch had her do the solo all over again. All one could think was: thank you.

Last spring, Shivalingappa performed an evening of contemporary solos created for her by Bausch, Ushio Amagatsu, her mother and herself at the Joyce Theatre. I caught up with her in Sarasota, Florida, where she is performing Shiva Ganga at the Ringling International Arts Festival after dancing a modified version at Fall For Dance in New York (review). She travels with four excellent musicians, with whom she has a strong partnership and who play an important role in the development of her Kuchipudi programs. When she points out to me that they eat only Indian food, I wonder aloud how they manage in places like Florida; no worry, she assures me, they bring their own ingredients and cook at the hotel. Standing in the lobby of an almost aggressively nondescript Residence Inn, she is slighter than she appears onstage, and impeccably polite. She speaks in a crystalline, delicate voice, in a vocabulary as precise as her dancing, and is quick to laughter.

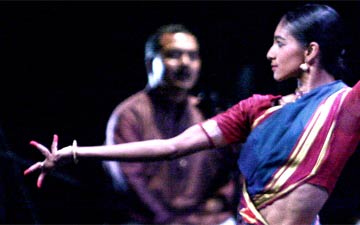

© C. P. Satyajit. (Click image for larger version)

I’ve read that you were born in Madras but grew up in Paris.

Yes, we moved to Paris when I was only a few months old. My parents went to Paris as students and met there. My mother went back to India to have her children and be with her family, but when we were just a few months old she returned, with my brother and me. I have an older brother.

Do you feel more French or Indian?

I feel comfortable in both places. I’ve always grown up being in France and having Indian parents so it seemed very natural to have that kind of mixed upbringing.

How many months a year are you away?

I’m away a lot. I live in Paris, but I’m there maybe three months in a year. When I have a longer amount of time, I usually go and spend it in India.

When did you start dancing?

When I was five or six. My mother [Savitry Nair] is a dancer and a teacher. She used to take me with her when she traveled, performing or teaching, so I started very young. You know, when you’re young, you always imitate what you see. I started taking classes with her when I was 5 or 6. She had classes in Paris twice a week and I just joined in.

You mother is a specialist in Bharata Natyam—what led you to Kuchipudi?

My mother is also a Kuchipudi dancer and I used to go with her to her classes in Madras. She learned from Master Vempati (Vempati Chinna Satyam) who then became my master as well. I think when I was about fifteen or sixteen, my mother was preparing a choreography for two Indian dancers—one of them was me—and one ballet dancer, and she wanted me to learn a variation in the Kuchipudi style. So the next summer, when we went to India, we went to her master to learn a variation. I learned a short choreography from his son and it was an epiphany. I completely fell in love with the dance. Something happened at that moment with that particular dance, and it changed everything. I became crazy for Kuchipudi and didn’t want to do anything else. I just dropped Bharata Natyam completely.

© C.P.Satyajit. (Click image for larger version)

What is it about Kuchipudi?

I think it’s a combination of things. Definitely it’s also related to my master’s style and persona. He was an extremely creative person and very innovative as well. On the one hand, he comes from one of the very traditional Kuchipudi families, but at the same time he was extremely open to the world, with eyes wide open, always looking for influences and allowing himself to be inspired by anything he found beautiful; from other styles of dance, a lot of Odissi, a lot of the folk styles, and martial arts, whatever he saw. Of course there was a lot of communication between Indian styles, because they come from the same roots, and sometimes, when they developed in the same area, they had access to the same influences of folk styles and literature. But his Kuchipudi style is extremely personal and specific. What I love about it is the combination of contrasts: something very strong in the legs—it’s very intricate and quick in the footwork and also very anchored into the earth—but the upper body is full of grace and swaying and undulating. I love the contrast between something very strong and rooted and powerful and at the same time extremely graceful and fluid and lyrical. And musical. Dance in India is inseparable from the music. They are just one [places the palms of her hands together to illustrate]. Actually it’s one discipline in the beginning: dancing, music and theatre.

I remember that in your solo, Swayambhu, you actually sang as well as danced.

Originally dancers could sing and play instruments and actors could dance. Everyone knew a little bit how to do everything though they had one specialty. And it was not uncommon for dancers to be able to sing very well and to know a lot about rhythm, and even today you should know a certain amount about music and rhythm and all those things. My master was extremely musical. It’s not something he taught you with words, he didn’t tell you all these things, but you observe. I suppose I was sensitive to it, because it’s something I find fundamental to any dance, but to Kuchipudi especially, it’s really bringing out the raga, the mood, the lyrics, so the whole thing comes together with the dance. It should be one whole [with great emphasis]. That is something I feel in my body and I think my master had it very strongly as well. When you see his choreographies, you feel like the music is dancing and the dance is making music.

Do you often sing in your Kuchipudi performances?

That was the first time. I’ve been singing since I was very little, very separately from dance. But you need to know about music when you dance, you have to be able to sing the song so you know the rhythm and you know the feel of the songs. I guess it developed into something I felt I could explore onstage.

© Hector Perez. (Click image for larger version)

It felt very private.

My singing is more fragile of course because I haven’t been singing in front of people for a long time. When I started doing Swayambhu that was the beginning. It’s a completely different approach to breathing. As a dancer you learn to control your breath in a way that you can master, but when you’re singing it’s completely different. I had this idea of singing onstage in a dance, but leading up to that I had a few steps that helped me towards it. There’s a duet that I do with a contemporary dancer, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, [Play, 2010] and we sing a lot in that. We had been working on it for 2-3 years. So when I did Swayambhu it was not the first time I had done it.

Is your style slightly more abstract, less based on storytelling, than that of other Kuchipudi dancers?

Well, usually in a solo evening there is less storytelling, maybe one piece in an evening. But it’s also my choice to devote myself more to movement-oriented choreography. You take a theme, and you work around that… I guess I’m more attracted to pure movement; my interest in storytelling came a bit later.

Your mother also reached out into other realms of dance, for example she taught at Maurice Béjart’s school, Rudra, in Lausanne. Did that influence you?

© Maarten Vanden Abeele.

I grew up being exposed to a lot of different things. At the same time she didn’t really cross boundaries in that she performed Indian dance as it was. But we would go and see a lot of different things. That gets into your psyche. I was very reticent about contemporary dance for a really long time. I enjoyed watching it, but I didn’t feel like I wanted to do it or like I had anything to do with it really. Especially once I fell in love with Kuchipudi, nothing else interested me for myself. Going toward contemporary dance happened in steps, and basically mainly happened with Pina Bausch. I loved her pieces and was very moved by them and touched by them. I was aware of her as an artist but also as my mother’s friend. I had a very warm feeling for her already. Every year we used to see her shows. For me, she was part of the family scene as well as part of the dance scene. The first tour I did with my master [in 1994], Bausch invited us to Wuppertal and we performed there and did a workshop for the company. She and my master had a strong rapport. And then whenever she saw me perform with Bartabas, or Peter Brook, or in Indian dance, she was always quite present. It was an ongoing thing for quite a few years. And then one day she said “I would like you to be in one of my pieces, why don’t you come be a guest dancer?” It was a piece called O Dido (1999), a co-production with Rome. I said yes, because I loved Pina so much, and I loved her company, but I didn’t really know what I was getting into. It was a very slow process. I’ve done a few pieces with them, and whenever these pieces are toured, I join the company, once or twice a year, sometimes more, sometimes less. I’ve been in Nefès, Bamboo Blues, and O Dido, and for a few years, I also danced in Sacre du Printemps.

At that point, did you begin studying other styles of dance, like ballet?

I used to join the company warm-up in the morning, I just followed what they did. I learned to be aware of my body in a different way, thanks to that. One of the big steps was learning Sacre du Printemps, because my training for that was much more in-depth. I took the warm-up in the morning more seriously and everyone helped. [All Bausch’s dancers are ballet-trained.]

Did you find Bausch’s technique challenging?

It’s definitely challenging, but her technique seemed very organic, so it didn’t feel alien to me. It just made sense. I fell in love with these steps, I really loved doing them. Maybe I couldn’t find the way immediately, I didn’t know how to shift my weight or understand with my mind, but I took the time. And I had the same feeling of passion for those movements as for Kuchipudi. Once you have that, you find a way of doing them somehow. Realizing that I was able to do those movements, that was a revelation also. I think it has to do with the fact that I’ve been exposed to a lot since I was a child. When you’re exposed to only one thing, your mind sets into that and it’s difficult to open it to other forms, but I had a very wide opening already.

© Nicolas Boudier. (Click image for larger version)

How are you seen in India?

Well, I don’t perform much in India, because I live in Paris and my whole dancing career has been outside of India. India has a different network completely. Also, when I fell in love with Kuchipudi, the strong feeling that I had was that I wanted everyone to know about it. My initial intention was to dance outside of India, to make Kuchipudi known outside.

You must be invited to festivals in India, though, or is it a very closed network?

It is. It’s opening up more, but not much until now. In a sense I understand because there are so many Indian dancers in India doing the art right there. Why ask someone who’s living somewhere else?

Do you see changes in the Indian Dance esthetic?

Yes, there are changes. But again, I’m not so hands-on with the classical dance scene in India. When I’m there I don’t see so many performances. I really concentrate more on working with my musicians and going for resources I can get only in India….

Is the technique of Indian classical dance changing because people are so much more athletic now than say fifty years ago?

I’m not sure. I think there are not a lot of people who do Indian dance in an athletic way. Kuchipudi is extremely strenuous, but not a lot of people do it that way. That’s how it’s intended, and that’s how my master taught it to us. You have to have the stamina, you have to be in good shape, and you have to practice to be able to do that. I guess that concept is more common here than in India. I’m not sure why exactly. The athletic aspect is a key element in Kuchipudi. But there’s also the narrative part, and a lot of people concentrate on that. The body language is not developed so much.

But the clarity of your dancing springs in part from your technique.

I think that comes a lot from my Western approach.

Has working with Bausch influenced your Kuchipudi dancing?

Yes, in a lot of ways: my whole approach to movement, to space, to musicality, to feeling, dynamics, symmetry, everything. Also, my work with Amagatsu. My Kuchipudi today mirrors all that. One of the strengths of any classical style is that it is flexible. You have to find those places, and of course you can’t move everything around. But there are areas that allow for innovation and flexibility, that are permeable to a lot of influences. That’s where classical styles get their ability to evolve with time and to be alive in the moment.

© G. Wilson. (Click image for larger version)

Are you changing the vocabulary of Kuchipudi?

No I don’t think so. First you have to forget everything else and do only Kuchipudi and get into that feeling—it’s a very organic feeling— so that whatever you do after that, you know, if you are doing something that is going away from that, maybe it’s not the right way.

So you’re not interested in breaking boundaries or transforming the form.

Not at all. I’m more interested in continuing my master’s line. He inherited this traditional form, which he worked very hard at all his life, with the best musicians, composers, texts, and rhythms, to take it to the next level. And of course with his genius and creativity. I think his innovation is what makes his Kuchipudi what it is today. It has that traditional and classical flavor and strength, but it’s so creative and innovative, that it’s surprising, and incorporates all these wonderful little details.

How did Bausch influence you?

I think a sense of dynamics of movement, symmetry, asymmetry. She always wanted to be surprised. She would say, “surprise me,” and I think that’s something that stayed with me. I also think about that. Because with Indian dance it’s predictable in a sense; you do things on the right and then on the left. So I think about how to break that symmetry at certain moments, not all the time, just the right amount that makes it relevant and exciting and unpredictable. I think unpredictability is something she was very attached to and resonates in me as well. And dynamics—I’ve always been fascinated by the dynamics of her dancers, the way they move, the speed that suddenly goes into something really slow but with the same energy. How to incorporate that kind of visual, energetic thing into Kuchipudi. I think it’s already there, but maybe it has not been brought out enough. I think a lot of things are there, but it depends on how you dance them yourself.

Your experiences with other choreographers have given you the ability to ask questions.

I don’t think about it as questions. For me it never happens much in an intellectual or word-based way, it’s always very organic or intuitive.

How do you develop your solo evenings of Kuchipudi?

Usually I choose a word or a theme that’s going to be my fil conducteur, my core. It becomes the measure by which I see what else is needed. But then it’s also about the music of course.

Do you improvise with your musicians?

No, I don’t improvise with the musicians at all. Sometimes I have ideas of songs that I love and that I have known a long time and would like to dance to. And my musicians propose a lot of music as well, within the classical repertory. Then there are pieces that are composed, but the lyrics come from traditional texts. The singer [J. Ramesh] composes new music, and there’s a lot of back and forth. He proposes something and I propose something, and he has ideas and I have ideas… The singer is in charge of the raga and both percussionists [B. P. Haribabu and N. Ramakrishnan] divide the rhythmic parts between them. The flautist [K.S. Jayaram] also proposes songs to me. Maybe I have a particular idea for a song I want to use for the invocation, then I need to have rhythmic patterns of a certain duration, and with this kind of idea, and I go to the two percussionists and say, “could you do a bit for here, and another one for here.” This is before anything else happens. I need to have all the music and all the rhythms ready, let’s say eighty percent, and then I go and make the choreography, and then we have rehearsals together for maybe two or three weeks, and everything is worked out, all the details.

© Hector Perez. (Click image for larger version)

Do you listen to the score together and say let’s do more of this or that?

Yes, except we don’t have so much time to sit together, but they send me files and I listen to them. I’m very slow. I listen and listen and listen and listen, and it has to start taking form in my mind. But what happens is usually that they give me a lot of stuff, and then when I’m choreographing I pick and chose and eliminate. And at the end, when everything is more or less ready and we have those two or three weeks together, that is where the fine-tuning happens. Then it becomes very detailed. By then I have eighty percent of the choreography, or more.

You seem to have a wonderful relationship with your musicians. Do you always work with the same people? They watch you so closely.

Yes! They have to. Everything is set, but at the same time, every evening is different. Certain songs have to have a certain pace, which is slightly variable because we’re not machines. Within the choreography, everything is set, but there are also cues where we have to be together. They have to follow me.

Have you ever thought of doing ensemble choreography in the Kuchipudi style, or collaborating with another Kuchipudi dancer?

No. To be honest, I’ve not seen a Kuchipudi dancer who made me feel like “oh my god, I’d love to dance with you.” At the beginning, I used to dance quite a bit with my master’s son, who is an exquisite dancer. But after that it’s mostly been solos. I suppose I got used to doing solos. The journey of doing a solo is quite intense. That intensity is something I look for. Also, I dance with others with Pina Bausch or Larbi [Cherkaoui], so I get my time with others. But this is a very solitary moment of being by myself. It’s a very personal journey. Of course you’re giving it out to the audience but it’s also your own personal journey.

Does every performance feel that way?

Yes. Of course, some performances are more intense than others but the expectation for each one is equal. With each you hope that you can go on that journey and touch something else. It doesn’t always happen, but that’s the wish. Our dance and our music is an offering and that is the core motivation, the essential point, why we dance and why we make music. That is a very strong motivation. Every day it has to be that.

© Hector Perez. (Click image for larger version)

Is it the music that creates that sense of going on a journey?

Yes, the music, the feeling behind it, the intention behind it, the intention that you wish for with your dance. It can be intense in a simple way. And that’s another thing I was going to say about Pina Bausch: simplicity. Simplicity is one of the essential factors. It’s always a measure for me. Is it necessary? If not, then take it out.

Are there people that you trust, who give you their opinion when you’re developing a dance?

No. That’s something I got from Pina. She never listened to anyone [laughs]. My mother is involved, she’ll come and say what she thinks, but during the choreographic process, I don’t let her come. She comes toward the end when we’re practicing with the musicians. I think we all have a clear compass if we know how to listen to it. The thing of not letting anyone else come in, it’s not because I think I know better than them, I’m sure they have a lot of amazing ideas, but I’m trying to allow myself to listen to that, if I can. Because I think we all can. Basically, I don’t think it’s me doing anything, I think we’re just instruments for something coming from somewhere else. If we can allow ourselves to be very transparent, clear, open, empty, then it can happen. You have to be ready. But you have to be qualified, use your talents, train yourself, practice every day so that your legs are strong, to give yourself the full range, but then be quiet. Try to be in touch with whatever is inside and waiting to come out. I’m always expecting to be surprised, and I don’t know whether I can do it.

Do you try to push yourself in new directions with each new piece?

I try to apply myself to the task at hand. It’s a very artisan kind of way. What you can do is learn the craft, but I myself don’t know what I’m capable of. I don’t know whether I can do a choreography. I know I’ve done so in the past, but does that mean I can do it again? I don’t know, I have no idea. And a lot of the time I think I can’t. I don’t want to do it. But at the same time obviously there is something inside you that drives you toward it and it’s not letting you not go toward it. So when it’s strong enough that it brings you to opening the door, then you have to open the door. There’s not a lot of doubt but there’s not a lot of sureness or confidence either. You don’t really know, but maybe yes.

Marina Harss’ interview of Shambala Shivalingappa is, sans doubt, one of the

very best and most sensitive explorations of an Indian dancing artist I have

read. It was simply splendid, and particularly because I am such a fan of hers.

[…] October, I interviewed her, and she proved to be as gracious in speech as she is graceful in movement. She told me: […]