© Tim Summers. (Click image for larger version)

Mark Morris’s Ode to Eccentricity

Mark Morris Dance Group

Ringling International Arts Festival, Quadruple bill:

Canonic ¾ Studies, A Wooden Tree, Silhouettes, Grand Duo

Sarasota, Mertz Theatre,

11 October 2012

markmorrisdancegroup.org

ringlingartsfestival.org

Mark Morris’s musicality is well-known – music is the reason why he choreographs, as he has said again and again, in various ways, to anyone who asks. This is why musicians love his work: it’s like watching the score reveal itself through the steps. Afterwards, one hears the music better. This also explains why he has often been accused of “Mickey-Mousing” the music, or of creating musical visualizations. It’s true in a way, but try it and you’ll see, it’s not so easy. What makes his “visualizations” so compelling is that in reality they are not slavish at all; they are the product of a fertile, irreverent, and very personal imagination. A Mark Morris dance has the stamp of his choreographic fancy written all over it. He does not meet the music halfway; rather, he appropriates it, filters it through his particular eye: Seattle-born, folk-dance trained, florid, outrageous, witty, and, deep down, quite melancholy, even solitary. For Morris, dance-making seems to be a way to listen and engage music as part of a group, a community (his company).

Which does not mean that every piece works equally well, of course. He can be too clever by half, and his humor tends toward archness. Sometimes one can get the feeling that, for one reason or another, he has not quite found the key to unlock a particular piece. It happened with the recent Renard. In Mozart Dances – one of his great works – it wasn’t until the second movement that one sensed he had truly tapped into the deep undercurrents in Mozart’s sublime, soul-stirring music. In his Romeo and Juliet, it never happened – one could feel Morris fighting Prokofiev’s deeply programmatic score. (In fact, the idea for that ballet did not come from him but from Leon Botstein and Sam Morrison, a Prokofiev scholar who had discovered an early version of the score in the Russian archives). But more often, Morris reveals an instinct for picking just the right music for whatever mood he is exploring and finding just the right vocabulary with which to interpret it. This is even more striking when the music includes text; Morris is one of the few choreographers who is drawn to vocal music. His interpretation works on multiple levels: kinetic, rhythmic, thematic, and textual. In these cases, his choreography becomes a multilayered translation take Socrates, for example, or his Dido and Aeneas.

© Tim Summers. (Click image for larger version)

There is also an admirable simplicity of means in much of Morris’s work, a restraint that approaches minimalism. In both Dido and Socrates, for example, the vocabulary has been pared down to the smallest possible number of recurring motifs, used in countless ways. If one removed just one element, it seems, the whole thing would fall apart. Some accuse him of oversimplification, as if he were making dances for the feeble-minded. I understand the criticism and yet it might be argued that this simplicity is at the very core of his art.

All this and more was on view this past week at the Ringling International Arts Festival in Sarasota Florida, where the Mark Morris Dance Group performed an evening of four dances. (I attended the Oct. 11 performance.) The big draw was the new A Wooden Tree, which had premièred just a few days before at the “On the Boards” festival in Seattle (Oct. 4-6). For starters, it contained a secret, or not-so-secret weapon: Mikhail Baryshnikov. The participation of the great Russian dancer, who of late has been devoting more of his time to theatre – he’s in his sixties after all – was revealed at the last moment. That said, he received no star billing; he was simply part of the ensemble. What was curious about A Wooden Tree is that it did not include much dancing in the traditional sense. It was as if Morris had decided to do an experiment: to make a dance with as little dancing as possible, practically a pantomime. Once again, his musical choice was the key factor: he used recordings by an eccentric Scottish poet and songwriter, Ivor Cutler (1923-2006), a man so deeply odd that the Beatles put him in their Magical Mystery Tour film. (The title, A Wooden Tree, is drawn from one of Cutler’s songs.) Cutler may be well-known in other parts of the world, but I’ll admit I’d never heard of him, and I’m thankful to Morris for bringing his weird little world to my attention. His ditties, which last about a minute, are odes to eccentricity and awkwardness. In a fluttery, Scottish-accented voice, he sings lines like: “I spread my brains out on the table and poke them about with a fork,” or “I love you but I don’t know what I mean.” Meanwhile, he accompanies himself on an out-of-tune harmonium or piano. As Cutler’s voice announces at the start of the dance, he is an “oblique musical philosopher.” One can’t help but feel that he must have been an intensely lonely man.

© Tim Summers. (Click image for larger version)

In response, Morris has created an equally eccentric, awkward little work, in which Baryshnikov and the rest of Morris’s crew are given free rein to explore their inner introversion. Garbed in Elizabeth Kurtzman’s dowdy Scottish wear – scratchy-looking woolens, caps, unflattering dresses, sweater-vests – they interact, clumsily court, briefly couple, or act out little scenes. The women’s hair looks unwashed, the men – including Baryshnikov – are the opposite of dashing. In “The Market Place,” Cutler sings: “how do you court a woman, do you run up to her and seize her?” The men do just that, grabbing the women unceremoniously but also maladroitly, like loners with scant experience around the graceful sex. In “Cosmos,” Baryshnikov and Jenn Weddel sit in chairs facing each other; her legs are ungracefully set apart, feet planted flat on the ground, back rounded, as if weighted down with disappointment. Cutler sings, “you are the center of our little world, and I am of mine, now and again we meet for tea, were two of a kind.” Every so often, they turn to look behind them, as if worried that even this modest measure of happiness might be snatched away.

At times, the darkness is even more pronounced, as in “Phonic Poem.” In a choppy, child-like voice, Cutler recounts a story: “A car can go fast on a hill.” Five dancers at the rear of the stage mime driving along in a car. Michelle Yard sits at a distance, listening. “Cannot stop so it has a spill”; the dancers fall about in grotesque poses. “Mom and dad get a cut, see Bill bleed, bleed Bill bleed.” The dancers return to their original positions, and the scene is repeated again. “Bill is dead, he lost his blood in the crash.” Michelle Yard covers her face with her hands. Black-out. (It’s hard to describe the impact of this simple scenario.) After all this bleakness, the final number (“Cockadoodledon’t”) restores some vestige of hope; Baryshnikov joins the rest of the cast in a silly dance, in which each person does his or her own thing; at the end of each phrase, they count out “1-2-3” with their fingers, until, for no reason, it becomes “1-2-4.” And then it’s over.

© Marc Royce. (Click image for larger version)

The music for the rest of the evening was performed live, as usual, by the excellent pianist Colin Fowler, joined by the violinist Aaron Boyd for the final work, Grand Duo. Canonic ¾ Studies is a poetic little piece (1982) set to various pieces in ¾ time, arranged for the piano. The whole thing has the feel of a ballet class for not-so-talented students, with all the anxiety and effort that implies. (Morris’s dancers are wonderfully straightforward actors.) Simple balletic steps and positions (arabesques, attitude turns, pliés) are peppered with Morris’s casual, everyday postures as well as his deftly percussive footwork. His ability to fit accented, syncopated steps into the music – probably a product of his early studies in Slavic folk dance – is a talent for which one is endlessly grateful. The work ends with one of Morris’s ecstatic circle dances, in which joy is equated with the communal act of dancing together (which takes on a very different hue in Grand Duo). The least substantial piece of the evening was Silhouettes, a duet for Dallas McMurray and Aaron Loux (it has been performed by dancers of both sexes in the past) set to Richard Cumming’s Silhouettes, played by Colin Fowler. The two dancers, wearing two halves of a pajama set, doodle around the stage in simple balletic phrases, intentionally performed without the taut, stretched bodies of ballet. The idea is that they’re just two everyday boys, doing pirouettes en attitude and petit allegro jumps.

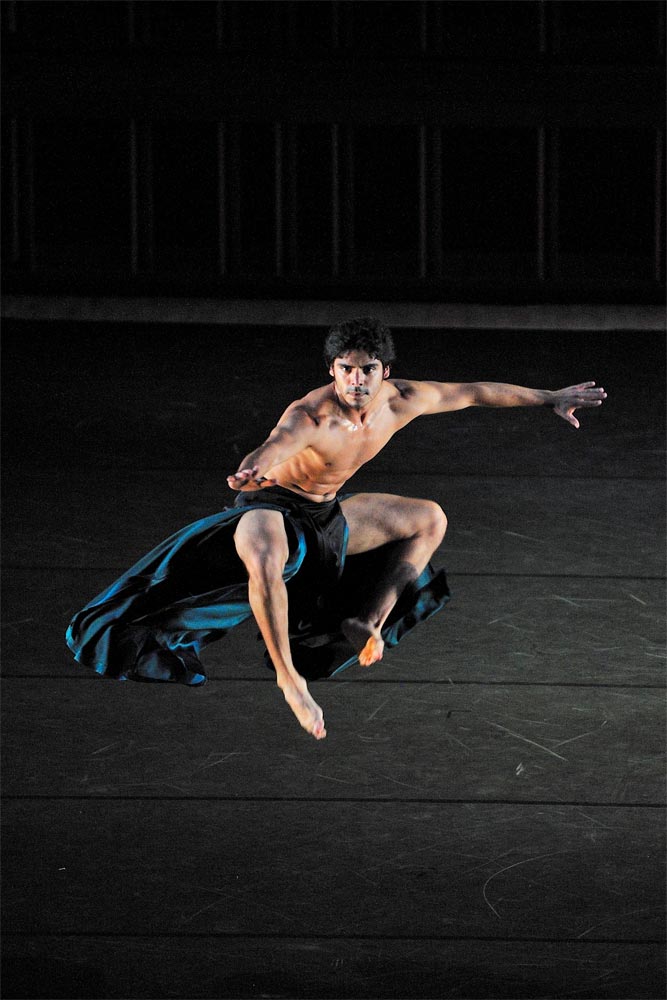

© Katsuyoshi Tanaka. (Click image for larger version)

This was followed by Grand Duo, a powerhouse of a dance from 1993. Here, all pretense of flippancy or awkwardness disappears. This is a piece about brutality, violence, our primitive nature. The music, Lou Harrison’s Grand Duo for Violin and Piano, is disquieting and beautiful, from the slow sinuous melody of its opening phrases to its final, off-kilter folk-dance, worthy of Shostakovich. Morris’s marvelous musicality is once again revealed. In low light, wearing costumes (by Susan Ruddie) that include skirts for the men, they resemble a tribe. One dancer, Maile Okamura, reaches toward the light, smearing her fingers to the sound of the violin. The gesture, which truly resembles a person smearing paint or scooping out peanut butter, is faintly repulsive, and captures Morris’s ability not only to reflect, but somehow viscerally to translate the feeling of sound in unexpected ways. It returns again and again throughout the piece. The second section degenerates into a pitched battle between two bands, punctuated by rough jumps, stomps and jabbing arms tracing a violent zig zag across the body. (Again, this gesture is the physical manifestation a slashing sequence of three notes in the music.) The movement is muscular, explosive, and rigorously unisex. One band advances, then the other, then they move in counterpoint. By the end, the body of a single victim lies on the ground as the battalions slice and leap around it. The final section is a rousing, menacing folk dance – a war dance – full of syncopated slaps of the legs against the thighs. It’s a mighty dance, and one of the best finales around.

You must be logged in to post a comment.