© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet

Program B: Divertimento No. 15, Prodigal Son and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue

Kennedy Center

Washington, Eisenhower Theater

9 November 2012

Suzanne Farrell Ballet website

Suzanne Farrell interview (November 2012)

The company premiere of The Prodigal Son was the centerpiece and highlight of the Suzanne Farrell Ballet’s second all-Balanchine program at the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater – a program that also included Divertimento No. 15 and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

The Prodigal Son is one of the oldest Balanchine ballets that survived – only Apollo (1928) is older. George Balanchine was just 25 years old when he choreographed it for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The ballet’s scenario, based on the Biblical parable of the prodigal son, was suggested to Diaghilev by his librettist, Boris Kochno. Balanchine commissioned the musical score from Sergei Prokofiev, whose compositions he praised and admired. (Yet for Diaghilev, it was always Igor Stravinsky – “the living embodiment of genuine enthusiasm, of genuine love for art and of eternal searching” – who was the unrivaled genius when it came to music for ballet. Stravinsky’s popularity in Paris was enormous. Prokofiev, on the other hand, desperately needed a hit with the public. His previous ballets for Diaghilev’s company – The Buffoon (1921) and Le Pas d’acier (1927) – enjoyed only a brief success.)

The premier of Prodigal Son took place atParis’s Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt on May 21, 1929. Prokofiev himself conducted. Serge Lifar, “fierce but vulnerable,” gave one of his great performances as the Prodigal; the tall and intense Felia Dubrovska danced opposite him as the Siren. The premier was a triumph – the ballet resonated with both the audience and the critics. As Balanchine once said, half-joking, it was “Lifar on his knees that made the ballet.”

The ballet tells the Biblical story of sin and forgiveness in three scenes. In the first scene, the young man rebels against his father, takes his inheritance and departs from his home. In the central scene, he squanders his wealth and “wastes his substance with riotous living,” spending his time with the Drinking Companions, a frivolous bunch, who eventually rob and abandon him. Here the rebellious runaway meets the tantalizing Siren, a femme fatale, and they dance an exotic pas de deux – “the strangest seduction in all ballet.” In the last scene, the son returns to his father on his knees. (Interestingly, the ballet’s final moments reincarnate to near perfection Rembrandt’s painting, “The Return of the Prodigal Son,” which Empress Catherine II purchased in 1766 for her collection and which has been on display in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage since 1852.)

The Prodigal Son was meticulously staged by Farrell for her company. The production had all the main aspects of the original ballet – its drama, exoticism and expressionistic style. It also featured scenery and costumes recreated from the original designs by French expressionist painter Georges Rouault.

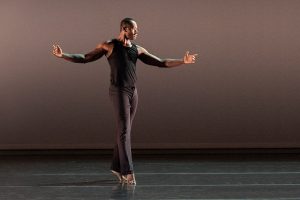

Michael Cook was ideally suited for the title role. He has a great physique and possesses strong technical and dramatic skills that the role demands. As the rebellious youth he moved with remarkable energy and dramatic force, conveying the Prodigal’s eagerness to be away and to be free. His enthralment with the Siren (Natalia Magnicaballi) proved a tense emotional struggle between inexperience and adoration. His final dragging journey home was as much pitiful as it was poignant. The statuesque Magnicaballi portrayed the Siren as a cold-blooded, conniving vamp, yet still managed to infuse her role with considerable allure and charisma.

The ballet reaches its climax in the final scene, when the Prodigal, humiliated and wretched, returns home and faces his Father (the excellent Pavel Gurevich). As the Father cradles his son in his arms and gently covers him with his cloak, the curtain descends.

© Rosalie O’Connor.

The evening’s program began with Divertimento No. 15 – a quintessential masterpiece of Balanchine, his fascinating take on classicism inspired by Mozart.

Divertimento No. 15 is an example of how Balanchine let the same music repeatedly ignite his imagination. His first ballet, Caracole, set to Mozart’s Divertimento No. 15 in B-Flat Major was premiered in 1952. Four years later, the choreographer returned to the score, which he considered the greatest divertimento ever written, and created a new ballet for eight soloists (five women and three men) and an ensemble of eight ballerinas to be performed at the bicentennial Mozart Festival at the American Shakespeare Festival Theatre. In its latest incarnation Divertimento No. 15 is a pure dance in which the choreography organically links the music and the dancers’ bodies, transcending the elegance and delightful charm of the Mozart’s score.

The ballet opens with a dazzling Allegro performed by the entire cast. The second part – Theme and Variations – is the ballet’s glamorous centerpiece, in which each of the five principal ballerinas gets a chance to shine in her own variation. The luminous Minuet invites on the stage eight ballerinas of the corps de ballet. The subsequent Andante is a showcase in its own right, featuring a series of five distinct pas de deux – one for each of the leading ballerinas. The majestic Finale – a brilliant kaleidoscope of movement patterns and groupings – brings the whole cast back onstage for the grand conclusion.

Elisabeth Holowchuk, Nancy Richer, Natalia Magnicaballi, Violeta Angelova and Heather Ogden danced the principal ballerina roles on opening night. Their cavaliers were Emanuel Abruzzo, Ian Grosh and Pavel Gurevich. The performance of the entire cast was radiant and bright. Even if the dancers sometimes lacked technical polish, their response to the music was perceptive and genuine, so the dancing, in a way, was the music’s mirror – a flawless reflection of Mozart’s sweet playfulness and buoyancy. Among the principals Ogden and Angelova particularly stood out for their amazing musicality and clarity of steps.

In the final dance of the program – Slaughter on Tenth Avenue – Balanchine merged Broadway, ballet and tap dancing with great humor and skill. In 1968, the choreographer re-worked the original excerpt from the Richard Rogers musical, On Your Toes (1936), into a stand-alone dance for Farrell and Arthur Mitchell. The ballet’s story revolves around a hoofer who falls in love with a striptease girl, who helps save his life in the ballet’s surprising finale.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Slaughter has an unusual opening for a ballet. It begins in front of the closed curtain, with a jealous Russian dancer Morrosine (Pavel Gurevich) hiring a Gangster (John Michael) to assassinate the Hoofer (Kirk Henning) and instructing him to fire a gun at the precise moment in the ballet when the tap dancer pretends to kill himself. While the gangster takes his seat in the parterre, Gurevich, speaking with a perfect Russian accent, declares to the audience: “And now I will show you who is the best dancer!” and, with aplomb, executes a set of perfect entrechats. After he leaves the stage, the curtain goes up on a lively saloon, the music starts, and the show finally takes off.

The Farrell dancers clearly enjoyed themselves in this seemingly convoluted comedy. As the Striptease Girl, Elisabeth Holowchuk looked more like a classy ballerina than a temptress; yet she was hardly a demure girl, delivering every step with high energy and haughty abandon. Her musical timing here was perfect as was her technical skill. An excellent actor and impressive tap dancer, Henning made the role of the Hoofer his own.

A ballet-within-a-ballet, Slaughter is decidedly a crowd pleaser; and the Farrell troupe brought it to life with their blissful dancing and superb acting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.