© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Divertimento from Le Baiser de la Fée, Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux, Bal de Couture, Diamonds, from Jewels

New York, David H. Koch Theater

27 January 2013

www.nycballet.com

Is there a ballet more deceptive than Balanchine’s Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la Fée’? If so, I’m not aware of it. The ballet begins like a pretty suite of dances for an ensemble of twelve women and a lead couple, and ends like a bad dream. For most of its duration it’s charming and sweet, perhaps even a little too sweet. Then, just as the ballet appears to come to an end, quite happily, the music moves into a different mode, as if introducing a vision scene in a fairytale. Forces begin to draw the happy couple apart. The woman bends back, as if she were being pulled against her will. Two women from the formerly cheerful ensemble lead the man away, holding his arms. The stage goes still, and everyone seems to have been put under a spell. The two lovers try repeatedly to find each other until finally the woman rushes across the stage and into his arms. But she ends up in an unnatural, almost grotesque pose, her torso bent way back so that only her legs walk forward, blindly, supported at the waist by her partner. They huddle on their knees, clinging to each other, but the women of the ensemble manage to glide between them through a hidden gap between their two bodies. By the end the man and woman appear to be lost in a wilderness, separated by half the stage, each unaware of the other’s presence. They retreat into the wings, torsos tilted back, arms reaching toward something beyond the stage. How can something that began so happily end so hopelessly?

In retrospect there are signs along the way. Balanchine’s original Baiser de la Fée, from 1937, was a fairytale ballet based on The Ice Maiden, in which a sprite kisses a young man at birth and returns on his wedding day to claim him as her own. The music, by Stravinsky, is a clear tribute to Tchaikovsky, Sleeping Beauty in particular. At the same time the orchestration has that transparent, slightly astringent clarity that is pure Stravinsky. There is even a touch of syncopation in the music for the corps, reminiscent of Rubies, of all things. (Andrew Sill’s conducting brought out both the shimmer and the rhythms, though not all the instruments sounded as solid as they should have.) The divertissement, which Balanchine created in 1972, has no plot, but somehow the imprint of a story is still there if one looks closely enough. It is most noticeable in the man’s solo, in which he seems distracted by something just out of reach (like James in La Sylphide). He lunges and leaps in pursuit, it eludes and torments him. It was only in 1974 that Balanchine added the haunting coda to the ballet described above. It’s hard to imagine Divertimento without it.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

At the matinee on Jan. 27 Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild were the lovers. Fairchild made his début in the role earlier in the week. Peck danced with great nuance, evolving from a kind of shy soubrette to a swooning bride, and then a woman in a trance. One could feel the air parting as she pushed it away with her hands, like a swimmer in water. When she dashed across the stage into her lover’s arms, she ended with a slide, a touch of abandon I hadn’t seen before. This season she is dancing with greater opulence than ever, taking the measure of just how far she can go with certain balances and transitions for extra effect. Since she has such control she can push very far indeed. Every transition is an event, without being an ostentatious display. Fairchild is still finding his way into the role. He has a natural instinct for building characters, but the shapes he creates are not always as clear as they could be; he acts the role rather than dances it. This was especially true in his solo. He neither bent low enough to the ground in the lunges, nor stretched upward enough in the jumps. Without contrast, the sense of urgency of the pursuit is lost.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

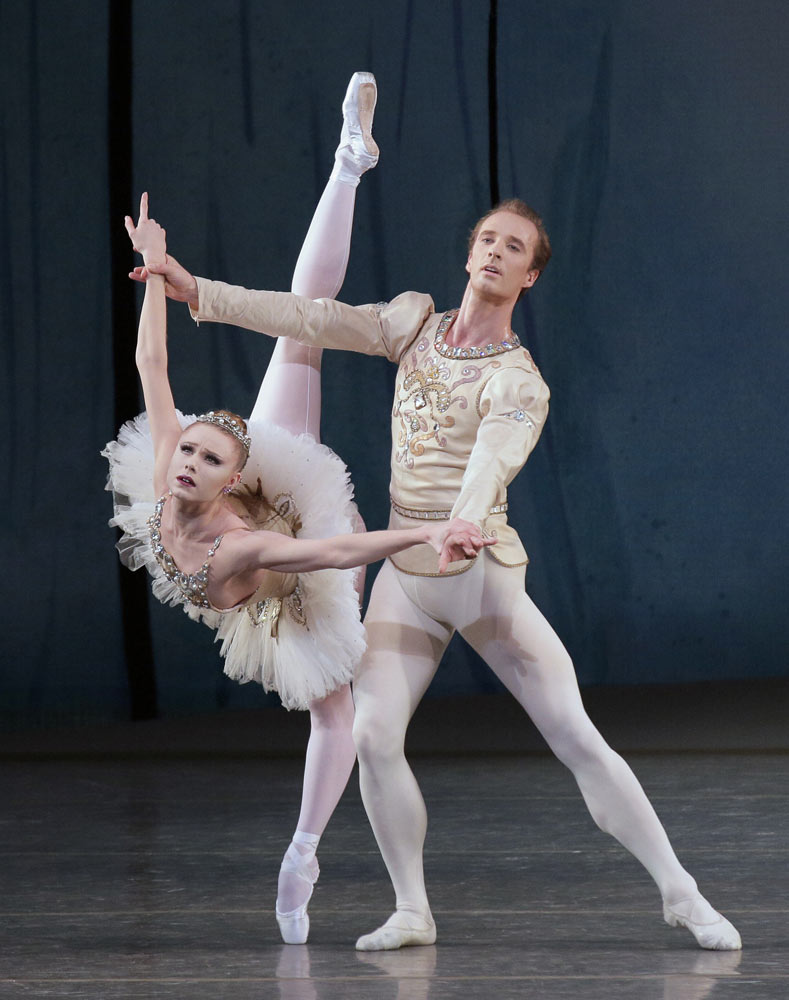

Chase Finlay made his début in Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux, alonside the prodigious Ashley Bouder. If only she toned down her knowing glances she’d be fun to watch. She seems to dance the entire ballet (and just about every ballet) in quotations, punctuating every dazzling feat with a question: “did you see that?” Her exaggerated self-assurance leaves little space for playfulness or joy. On the other hand, on this occasion, her self-possession allowed Finlay to worry less about his partnering, for which I’m sure he was grateful, and focus more on the challenge of his own steps. This little nine-minute showpiece is a killer, especially for a tall dancer like Finlay. At first he looked a bit cowed. But it soon became clear that he would do just fine, and moreover that his particular gifts – beautiful, soaring jumps, a deep plié, a wonderful through-the-body stretch – would bring a welcome amplitude to the steps. His brisés flew, his cabrioles hovered, his sissonnes flickered with joy. He danced with a mixture of seriousness and incipient pleasure, as if amazed at his own abilities. The performance wasn’t perfect, but it promised much.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

After a pause to show off Valentino’s deeply unflattering costumes in Peter Martins’ Bal de Couture from last season – hopefully this empty shell of a ballet will disappear quickly from the repertory – the matinée ended with a performance of Balanchine’s Diamonds, from Jewels. Sara Mearns, back from an injury which had kept her off the stage for nine months, was in rare form, dancing with that special intensity that sets her apart from other ballerinas. One could almost hear her thoughts as she slowly zig-zagged across the stage toward her cavalier (Ask la Cour) at the start of their pas de deux. The deep arch in her back in the duet’s many backbends expressed enormous yearning; each unfolding of the leg was a momentous, slow, deliberate affair. “I am your queen, and I have suffered long.” Like a great opera singer, Mearns is able to sustain endless legato phrases, melodies that modulate and stretch and leave the viewer gasping for air. “You’re sweet, but my life is elsewhere,” Mearns seemed to say as she walked at La Cour’s side or reached into the darkness, caressing her crown. Like Tiler Peck she sustains off-balance poses and turns for beyond one’s expectations, like a held breath. When Peck does it the effect is musical, but with Mearns it’s emotional, weighty, momentous.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Later Mearns Tweeted that she had hurt her foot before the show, but in truth she seemed more focussed, less emphatic in this performance than she had earlier in the season. There is always an edge of danger to her dancing. She plunges into positions and pushes them to an extreme; for this reason, she is usually paired with extremely reliable partners, like La Cour. Even so, unlike Divertimento from ‘Baiser’, Diamonds can feel like less than the sum of its parts. The waltz with which it opens is pretty but doesn’t add up to much; it seems to go on and on, showing off its diamond formations. At this performance, the scherzo that comes after the pas de deux was omitted (perhaps because of Mearns’s injury). The finale, a grand polonaise that evokes the wedding scene in Sleeping Beauty, is filled with pleasing patterns, lines intercrossing or moving in opposite directions or framing smaller groups in the center. The ensemble echoes elements of the pas de deux; here they become simply steps: stylized gestures, a touch of the head, a backbend, a slow walk in passé. The pas de deux’s spell slowly dissipates and we get, instead, one of Mr. B’s resplendent demonstrations of imperial grandeur. And set within this silvery parure is Sara Mearns, a kind of blazing diamond in the rough.

You must be logged in to post a comment.