© Elliott Franks. (Click image for larger version)

Catching the Wave: Paco Peña Flamenco Dance Company

Paco Peña Flamenco Dance Company

Flamenco Vivo

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

in collaboration with the World Music Institute

19 January 2013

www.pacopena.com

www.metmuseum.org

www.worldmusicinstitute.org

More than other dance forms, flamenco thrives on the illusion of spontaneity. It’s the reason why some of the best moments in a flamenco show happen after the show has ended, when the ensemble gathers at the edge of the stage, like a happy family or a band of tipsy friends, dancing for each other. The guitarists dance, the dancers sing, and everybody claps along. Dance returns to its most basic function: a communal activity, a celebration of joie de vivre and the pleasure of good music. Great flamenco dancers trick you into believing they are making it up as they go along, though a certain amount of pre-planning is obviously necessary in order to put on a show. They practice, they figure out new tricks, polish their technique and plan out well-structured routines that goad the audience into a frenzy without killing the performer in the process. The object is to produce a kind of ecstasy – the famous out-of-body state known as duende. (It’s the same reason ballet has moments like Albrecht’s endless entrechats in the second act of Giselle; the dancer jumps, over and over, until he is on the verge collapse, while the audience’s excitement grows and grows).

© Murdo Mcleod. (Click image for larger version)

This is also the reason why big, showy, tightly-choreographed flamenco spectacles with complicated concepts and fancy lights, copious dry ice, and battalions of well-toned dancers rapping their feet in unison are so disappointing. A lot of noise, but no ecstasy. The great Spanish guitarist, Paco Peña, knows to avoid the temptation of spectacle. His ensemble, the Paco Peña Flamenco Dance Company, has been touring off and on since the seventies. This weekend they performed his newest show, Flamenco Vivo, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (under the auspices of the World Music Institute). Peña’s ensemble is a lean operation: three guitarists, two singers, three dancers and a percussionist playing cajón (an instrument that is basically a wooden box). There is amplification (an unavoidable reality in any venue larger than a small room) but no extraneous stage design, and only the most primitive of lighting schemes. The set consists of five chairs, for the singers and guitarists to sit in. The dancers’ dresses are simple and elegant, lacking the usual extravagant flounces and color schemes or contemporary flourishes like leather pants, low necklines, etc, etc.

The program notes at the Met provided biographies of the performers but no set list. Peña, one assumes, wanted to keep things flexible. But the format was familiar: musical numbers, mixed with solos, duets, and trios for the dancers, and a finale for the whole group. At one point there was a solo for Peña – of course – and unsurprisingly it turned out to be one of the highlights of the evening. He played a granaína, a slow, Moorish-inspired piece from Granada. It was a long, lilting aria, with the dreamy atmosphere of a meandering river voyage at dusk. Peña, who is in his early seventies and has the look of a compact, ascetic troubadour, plays in a melodious, wonderfully crystalline style. Everything is distinct: melody, harmony and rhythms; he’s like three players in one, always subtle, never showy. Toward the end, a familiar-sounding folk melody bubbled up to the surface, like a memory, and then disappeared again. The piece was full of subtle hues; Peña’s improvised ornamentations were like poetic interludes, enticing explorations one was happy to embark upon and which eventually led back to the original flow. One could listen to him play all night.

The other two guitarists, Rafael Montilla and Paco Arriaga, were also excellent, and the musical play between the three was a source of pleasure throughout the evening. The singers – José Ángel Carmona and Cristina Pareja – were also good, though they lacked the emotional directness of some cantaores. Pareja’s voice, perhaps because of excessive amplification, had a somewhat strident edge at times. But even so the level of the music-making was so high that it set an almost impossible bar for the dancers, all of them veterans of the flamenco scene. The two women, Charo Espino and Daniela Tugues, are very solid performers, especially Espino, perhaps the most well-rounded dancer of the group. In her castanet duet with Peña, Zorongo, the two sat knee to knee, playing a game of musical catch; Espino answered Peña’s questions, completed his sentences, challenged him, teased him, trilled on his melodies. The two were remarkably in sync; she seemed to sense when he was about to slow down or begin a crescendo and responded almost before he knew where he was headed. At one point Peña, normally pensive, looked up at her and smiled.

It was the most relaxed moment of the evening for Espino, who also performed a nice seguiriya with her mantón, an enormous white scarf with fringe. It’s amazing how exciting the many ways of flipping and wrapping a scarf around the body can be, in the right hands. Most flamenco shows have done away with this sort of number – it’s a little old-fashioned and not as showy as the percussive footwork known as zapateado – but it’s a shame. But despite their polish, neither Espino nor Pareja is a particularly spontaneous or expressive dancer. The quality of their movement doesn’t vary much, and there’s never a sense of letting go; they wear that classic flamenco expression, intense, proud, almost angry, at all times. In tango they call it the cara fea, and it’s supposed to indicate that this is serious business. But without real emotion behind it, it’s just a mask.

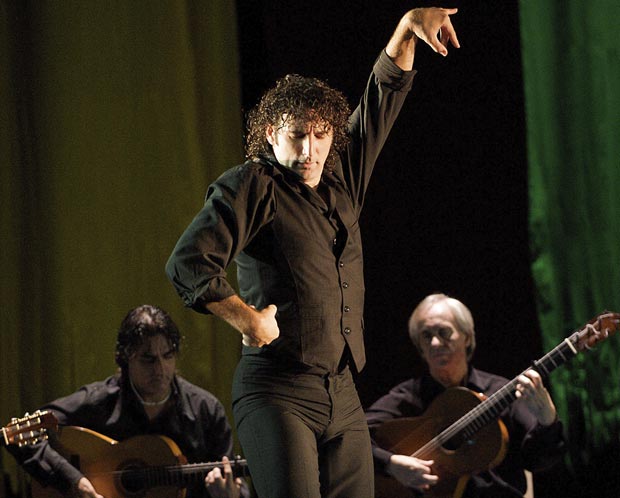

© Elliott Franks. (Click image for larger version)

Which brings me to Ángel Muñoz who, with Peña, is the real star of the show. The two couldn’t be more different: Peña is all interiority and nuance, while Muñoz is all bluster and instinct. But he has the goods to back it up. Thick thighed, broad-chested, with a mane of black curls, a smoldering gaze and a sultry overbite, he’s a bull of a man and an extraordinarily charismatic performer. He starts off slow, teasing the audience with swivels and slides of the foot, complemented by sweeping arm gestures. But when he gets going, there’s no stopping him. And it’s no thoughtless barrage of sound; his zapateado is full of surprises, sudden rhythmic shifts and syncopations. He varies from loud to almost inaudible taps and plays with subtle variations and accents, gradually building to a kind of wild frenzy. He’s got tricks up his sleeve as well, like taps on one leg and taps while traveling across the stage and while turning. But what really makes him thrilling to watch is the way he seems to enjoy himself and improvise the steps, taking the musicians and audience along for the ride. “What should I do now?” he seems to ask himself as he rises high on relevé, ready to pounce. He’s a master of suspense. And he really engages the musicians, often turning to them, egging them on. Like a surfer, his body tenses, ready to catch a wave; he waits and waits, circling the beat, and then, with a surge, he dives in. His two solos at the Met ended with explosive, witty, wild passages that brought the audience to its feet. He stared out, not in that impersonal, pseudo-intense way, but rather seeming to engage individual people, dancing for them and about them, drawing them into his world. He was playful and sensual and unpredictable and really, you really didn’t want the solos to end. That’s how flamenco should be.

You must be logged in to post a comment.