© Henry Leutwyler. (Click image for larger version)

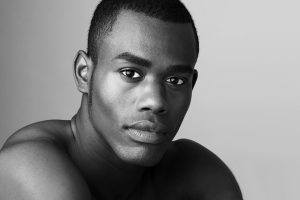

An Interview with Troy Schumacher

satelliteballet.org

www.nycballet.com

Creative breezes seem to be blowing at New York City Ballet these days. More interesting yet, they are originating within the company. Last season the corps dancer, Justin Peck, made an exciting new work, Year of the Rabbit, filled with complex patterns and allusions to everything from Les Noces to sports to relationships within the company. Meanwhile another member of the corps de ballet, Troy Schumacher, has been quietly toiling on his own independent choreographic projects. In 2010 he formed the artistic co-operative, Satellite Ballet and Collective, with Kevin Draper, a poet and multimedia artist whom he met by chance in the hallway of his apartment building on the Upper West Side. Draper introduced Schumacher to Nick Jaina, a Portland-based songwriter with a lyrical, folksy bent, and the Satellite Ballet was born. Together, and with the collaboration of a group of dancers from New York City Ballet, they’ve created a small number of ambitious, layered, multi-media works: Epistasis, Progress and Warehouse under the Hudson. Schumacher has taken on a huge challenge. Developing ideas as a group and managing multiple visions is, in some ways, even more difficult than coming up with ideas in isolation. But Schumacher is a true believer in the collaborative process, i.e. a real exchange of ideas throughout the many steps that lead to the creation of a new work, with room for debate and input from multiple sources. A certain suppression of the ego is indispensable. As he told me, “I’m not doing this so people think I’m a genius.” On the other hand the mechanics of this kind of exchange are increasingly facilitated by technology, which allows people to send digital files of music, choreography and visual design in an instant. Recently Schumacher was given the opportunity to work in a more traditional vein, through an invitation by the New York Choreographic Institute, New York City Ballet’s incubator for young choreographers. He chose to make a ballet for eleven dancers – his largest yet – and to set it to several movements from William Walton’s energetic piano quartet in D minor, written when the composer was only sixteen.

Schumacher and I spoke at the end of 2012, first in a café in Chelsea and then in his sunny, peaceful living room during a break in rehearsals for Nutcracker, in which he danced the roles of Candy Cane, Soldier Doll, and Tea.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Tell me a bit about your background…

My dad was a saxophonist and clarinetist; he played in a big band in New York for several years and he was also in a band called Nightflyte that had a top forty hit. My mom was a singer and actress who did a couple of national tours of Broadway shows. They met while my dad was playing in the pit of a show she was in. Then he decided he wanted to become a chiropractor. So they moved to Atlanta and he became a chiropractor and my mom became a housewife. But music was always a huge part of what was going on in our house. There are videos of me as a three year old singing Dirty Diana while wearing a Bowie wig. I have an older brother who’s a singer-songwriter. I remember seeing Ailey when I was young; I remember a woman in an arabesque penchée in Revelations. But I didn’t enjoy watching ballet or dance except for Gene Kelly and movie musicals. I loved Cats. That was my first real obsession. At seven I said I wanted to learn how to tap-dance. My parents just brushed it off for about a year and during that period I sort of loudly invented what I thought tap-dancing was. I’m sure it annoyed the hell out of my parents. And then finally they relented and signed me up for classes and I took my first class. I was so bad, and I had expected to be so good. I was devastated. I was almost ready to quit after my first class, but one of my mom’s friends, a former dancer, taught me some steps and in the foyer of her house we tapped around. I decided, “I’m going to figure out how to do this,” and I became a tapping machine. I generally don’t say that I’m good at anything, but I was really good at tap-dancing. For three years of my life I did nothing but tap and watch Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire musicals.

How’d you get into ballet?

At my first studio, Atlanta DanceWorks, they encouraged me try other dance forms, so I started taking jazz and some ballet, but it was like pulling teeth. At twelve and a half I woke up and thought, “they don’t make Broadway movie musicals anymore and I don’t have the voice to sing and be in shows. What am I going to do with this?” I knew I liked to dance, and maybe I was starting not to mind ballet so much. So I decided to audition for Atlanta Ballet’s Nutcracker. I got the Fritz role – they call him Nicholas. And they invited me to take a class with the other principal children in the party scene – this is what I consider my first real ballet class. I was more devastated after this ballet class than after my first tap class…. I’m not flexible, I don’t have the best feet, I’m not extremely turned out, but I decided anyway that I was going to try. Atlanta Ballet invited me to be in their pre-professional division and from then on I was just determined. My dad says he never even questioned the fact that this was what I wanted to do because I loved it so much. I became obsessed with the athletic element. I auditioned for The School of American Ballet (SAB) with Kay Mazzo. But I still didn’t care about anything but classical ballet: double cabrioles, 540’s, revoltades, a hundred Russian pirouettes, that’s all I did. Then I came to the school for the winter term. I watched New York City Ballet’s whole winter season, every night, but I really wasn’t into it. By the spring I was getting into it a bit more. I was in the fourth ring one night, watching Davidsbündlertänze, and halfway through it I found myself crying and experiencing something completely new. I think it was the first time I experienced art as something emotional. At that moment I fell in love with New York City Ballet and Balanchine.

What musical training do you have?

At SAB, I really got into teaching myself piano. I started at sixteen with Jeffrey Middleton; he taught us how to read music, and there was a piano in the SAB dorms. I got really good at reading music, which is something I’m thankful for now. I’ve always tried to make friends with all the ballet pianists I’ve been in classes and rehearsals with, and I sometimes turn pages for the pianists during performances at NYCB. I became good friends with Whit Kellogg, a pianist at SAB and the Metropolitan Opera, and he would get me tickets to the opera. I would go to Juilliard recitals and discover new pieces. I’m also really into jazz and the American Songbook. Lady Be Good was the first piece I could really play.

What ballets have been particularly significant to you as a dancer and a budding choreographer?

I’d say getting to dance Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the first time you get into a Balanchine leotard ballet. You feel like this is what you’re here for. Symphony in Three Movements, being part of this machine; Square Dance; Tombeau de Couperin.

Whom among the younger generation of choreographers do you find particularly compelling?

I was first drawn to Benjamin Millepied’s work when I saw a program of his at Florence Gould Hall. I remember being very interested in this way he has of creating new steps. I think he brings a nice social aesthetic, showing the way people relate to each other. He definitely comes at it from a more European point of view. And Christopher Wheeldon; the first time you see After the Rain is such an amazing experience. I think it’s fascinating how Chris has created this aesthetic and how he’s able to mold many different ballets in his style. I was so impressed with Estancia and the vision that he produced, so crisp, so fresh.

© Henry Leutwyler. (Click image for larger version)

Do you watch other companies?

I’ve started to more recently. I also find myself enjoying other forms of dance a lot more because I’m looking at it from a different perspective. I see as much non-dance stuff as I can, theatre, music, jazz, classical, art.

Are there any Downtown or contemporary choreographers you admire?

My first experience of Pina Bausch was the movie [Pina], which I saw three times. I was enamored with the dance cinematography. Dance is a difficult thing to experience outside of the theatre, but for the sustainability of the artform it has to find a way to make itself more widely available.

Did you see Pina Bausch’s Como el Musguito en la Piedra?

Yes. I was amazed by her dancers. They’re some of the best dancers I’ve ever seen in my life and they embody things that I value, like individuality and a sly athleticism. They can be beautiful, ugly, funny. They’re all so versatile. As a piece, it was missing a lot of structural elements and I was perturbed by many of the musical choices. Sometimes in watching dance there are moments that are so memorable that they really shape our experience. Pina Bausch was able to create moments like that. Moments that mean something or make you feel something.

So tell me about Satellite Ballet and your collaboration with Kevin Draper…

This whole thing started out as an experiment. When I met Kevin, we didn’t really know what was going to happen. I had only made one four-minute ballet for the Atlanta Ballet, set to Poulenc. The Atlanta Ballet has always been very supportive. I wanted to try my hand at choreographing far away from NY.

Did you suggest it to them?

I did, and they were very receptive. I called down there in the summer of 2009 because I had decided I wanted to try choreographing. We were on summer break. After Saratoga, I thought, maybe I should try? So I called them up and they said “sure, come down.” I chose Poulenc’s sonata for piano and cello, just one movement. I worked with five dancers, four women and one man. They let me use their trainees. They performed it as part of the trainee performance in the spring of 2010. Then in early 2010 I met Kevin and we started Satellite. One morning, I opened my apartment door and Kevin was moving in across the hall. He introduced himself and I told him I was at New York City Ballet, and he told me that one of his inspirations for going to architecture school was Noguchi. He knew a little bit about ballet and he has this performing arts space in Michigan in the middle of nowhere; he floated the idea of putting together a performance. He went to architecture school but he’s not a practicing architect. He works at a consulting firm. I’ve always wondered why people didn’t collaborate more, and he was interested in putting something together. So I went from making a 4-minute ballet to making a 22-minute ballet. Choreographing is never easy, and it’s not always fun, but it’s a singular experience unlike anything else.

Why are you so drawn to the idea of collaboration?

I’ve always been interested in looking at a ballet company and figuring out what could be done better. At SAB I started studying ballet history and I realized that you had two people, Balanchine and Stravinsky, already masters of their craft, who came together and created Agon. In many ways it changed their lives, it changed ballet and it changed Stravinsky’s music. Other art forms have always been important to me. I love music; I want to be involved with creating something with someone else. When you’re in the corps, the opportunity to go somewhere and dance on your off time is really exciting. Principal dancers do it all the time, but corps dancers don’t get the chance very often. Kevin brought up that he was a poet, and that he was really interested in the Manhattan Transcripts by Bernard Tschumi. Tschumi made this work that expresses the idea that space is defined by what happens in it rather than the physical space, which is something that really applies to dance. And Kevin said “there’s a composer I want you to listen to,” Nick Jaina, from Portland. Nick had played a show at Kevin’s performance space in Michigan. It’s basically this very honest indie rock music; it’s interesting, with a lot of feeling. New music is not always easy to listen to; but now there’s this movement of young classical composers creating beautiful. pleasing music, but I wasn’t really aware of it then. So I thought how great would it be to keep Jaina’s feeling but write it in a classical form and break out of conventional song patterns. Most of the intense collaboration has always been between me and the composer.

What comes first, the text or the music?

For the first ballet Kevin handed us about 100 pages of his poetry, something he was considering making into a book. We went through it and took what interested us. I’d been getting more and more into reading literature and had been reading Russian novels, but not so much poetry. I’ve come to really value a literary perspective in dance; I think we really hit on something in our second ballet, Epistasis, where we used a libretto written specifically for a ballet. We call them abstract librettos, because from the beginning I said that to just take literature and “tell” it in dance terms is not a very strong or feasible idea. You have to figure out how to take little bits and translate it into dance or music. One sentence can make an entire ballet, or even two words could do it. There are moments in Kevin’s poetry where I experience something and it sparks something in my brain. Also, half of making a ballet is structure. Sometimes I’ve taken how something appears on a page and turned that into a structural element, for example the solos in Epistasis, which were taken from a poem with six stanzas that all relate to each other. We took a concept from each stanza and applied it to a dancer; I choreographed a solo and the composers wrote a piece of music based on their impressions of each of the dancers. This part of the libretto was like a cross-section of the earth, with different layers, like a volcano. The first level is molten nickel. So we asked, whose personality is like that? Kevin also did the visuals. We want everything to cohere, so we share clips all the time. I like hearing feedback from everyone because I’m young and still growing, and hearing feedback from artists who know very little about ballet is fascinating to me.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

Is the music written down?

The interesting thing is that they’re indie musicians, so they have differing levels of musical education. Nick is basically self-taught. So there was no score and the musicians were playing these 20-minute ballets from memory. But I was interested in having a score. I’ve gotten to know Nico Muhly a little bit through Twitter and from working on [the Millepied ballet] Two Hearts. So I emailed him and asked him if he knew anyone who could help us create a score of our music. We wanted to see what the music sounded like with a really great ensemble playing it. Nico said “I know just the person, his name is Ellis Ludwig-Leone.” He arranged and transcribed our music over the summer, along with Nathan and Nick. So this time we had a score.

There seems to be an uptick in the number of in-house choreographers at NYCB – I’m thinking of Justin Peck, for one – is creativity encouraged in the company?

There’s a huge group of immensely creative people at NYCB that dabble in a ton of things. The company is supportive of people trying to choreograph because it’s needed in the field of ballet. The Institute is the main way that people get their opportunities. Peter’s been supportive of me starting Satellite Ballet; he came to our first performance and was very positive and gave really amazing feedback. The hurricane kept him from coming this year.

Do you ever feel like the Balanchine aesthetic is a kind of mental prison?

It’s a really strong aesthetic but at the same time I feel like it’s a three-walled room. You have what Balanchine did, which from a technical and choreographic perspective is just so “correct.” What I’m interested in is how to walk forward from this because the [Balanchine] training and the dancers are incredible. I’d rather watch them do ballet than anyone else. I spend a lot of time trying to think of how to take what he did and apply it to the social context of today. One thing about Balanchine is that his work reflects the ingrained royal formality of the Tsar and royal hierarchies and sense of chivalry – or you could call it chauvinism in some cases. It all makes sense, but if you make a ballet today where you have two people bowing to each other without making some kind of social statement, it doesn’t make that much sense. I’m really interested in exploring that….

How does that influence your ideas about partnering?

Chris Wheeldon always impresses me in this respect: his inability to do anything wrong in a pas de deux. I think that male-female partnering has this dichotomy of the man elevating the woman or the man manipulating the woman. At the same time there’s all this in-between. People really enjoy watching those moments. Everyone has moments in his or her life that are like that; we can all relate to it. I’m trying to mirror life more than an ideal.

You once told me that you were ambivalent about gesture in dance. What did you mean by that?

I’m not interested in pantomime or artificial gestures to express things that dance is not meant to express. At the same time, in life, people grab their heads, we rub a migraine, we hold somebody, we touch their back to keep them from leaving us. But grand motions, that’s the kind of gesture that doesn’t interest me.

But given that you work with libretti, or words, don’t you need gesture?

I’m not looking for dance to express words literally. Words, or poetry, make you feel a certain way; there’s a certain feeling that can come over you when you’re reading something. It’s one reason why I love reading Proust, because there are these moments where you don’t know exactly what’s happening but there’s something so beautiful that comes out of it. But I’m not trying to translate poetry into dance in a literal way.

But your last piece had a narrative…

It did, but it was more a series of narrative vignettes that were related to each other. There was a concept of time; the ballet took place over the course of two days. And there were physical interactions, but there was no pantomime, at least as I see it. There are narrative moments that words and movement can both express. One thing we’re very interested in trying to explore is allowing each art form to take the lead at different times. At times the graphics told the story, or the music.

How was this last season different for you?

I firmly believe that works should continue to grow and change and evolve. Especially being so young – I just turned 26. This was only my third ballet. This year, Epistasis was a much more interesting and valuable work than the year before. We expanded some moments and refined the way the graphics relate to the dancing. I spent a lot of time changing tiny moments, and we added two-and-a-half minutes to the ballet and took out a few moments and rearranged the music. I hired a new group of musicians, because now we have a score, and the musicians had time to refine it, and we added a cello. It’s a difficult thing to join all these elements together. Also: how much should you prep the audience? For Epistasis we decided to just allow the title to speak for itself. The whole libretto is pretty much contained in this one word. That leaves things open. Also, a lot of people don’t want to know anything beforehand.

© Erin Baiano. (Click image for larger version)

How do you deal with critics? The reviews for your last season were mixed.

Like many dancers, I read reviews. I enjoy reading them, not that I always agree. I want to hear everyone’s honest perspective. I take a lot into account, and dance critics come at it from a position of knowing dance and watching dance all the time. Even too much, sometimes. They point out interesting things. I’m not doing this so people think I’m a genius. I just want to create works and add something meaningful to dance and to ballet and also bring other people to dance with intimate, accessible performances.

It sounds like you have thick skin.

I try to. Obviously you want people to like what you do and I have my own internal process when I see a bad review. I think that anyone who says it doesn’t affect them is not being truthful. I think that even when you get a good review if there’s one bad sentence in it it affects you as much as a bad review. What bothers me when I read reviews are inaccuracies or unnecessary snark or pretending you’re being objective when you can’t be. What I value is an outside perspective from someone who knows a lot about dance. But I hope that eventually people will begin to see that this is not just a dance performance.

You want it to be looked at by people from outside the dance world?

Yes, and I hope that they will when we’re at the Joyce in August. Satellite Ballet will have two evenings at the Joyce, Aug. 14-15, part of a new festival called Ballet 6.0. It’s a group of new, smaller ballet companies, including Olivier Wever’s Wim W’Him, Company C, and Ballet X. We each have our own evening. It’s a co-presentation with the Joyce; they don’t pay us, we don’t pay them, which, coming from a position of having produced everything ourselves, is amazing. I’ll use more or less the same dancers. I like to work with the same people. I think they’re all really unique and they all have something to say.

What led to your split with Kevin Draper?

I think we have slightly different visions, but it’s mainly an administrative thing. I’m interested in working with some new people. I think if you keep working with the same people exclusively over and over you’re not going to grow. Nick Jaina is working with another choreographer. Satellite Collective is still going to exist, in Michigan, as a place to foster artists and incubate projects. Nathan Langston, our dramaturge, is creating something called the Satellite Press that we’ll all write for. For example, I interviewed Claudia LaRocco about dance criticism. For our shows at the Joyce we’re bringing in two new artists that I’m very excited about. One is Ellis Ludwig-Leone. He has assisted Nico Muhly on many projects. On the literary side we’re developing ideas with Cynthia Zarin. She’s a poet, and was a longtime New Yorker writer and one of Ellis’s professors at Yale. We all kind of educate each other. It’s important to be able to speak each other’s language. We’re still trying to come up with a new name.

You recently made a piece for the Choreographic Institute. How did that go?

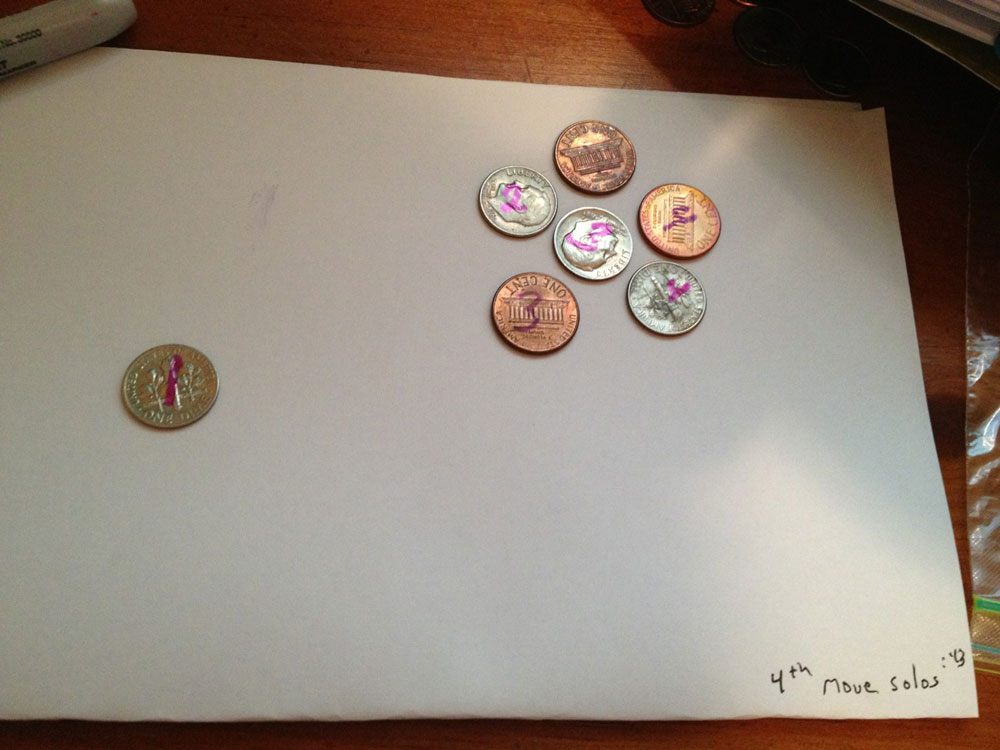

I happened upon a cd of the William Walton piano quartet on a trip to the library where I checked out about forty CD’s. I like to go through and pick up music without bias. I somehow grabbed two CD’s with William Walton pieces on them, mainly because I was interested in Elgar pieces on the same disc. The fourth movement of the piano quartet was the first thing I responded to; it seemed really fresh and contemporary. It had a great, danceable energy to it. Often, the best ballets are set to scores that seem to need another component; it’s like they’re asking for a visual element. I really wanted to create a ballet to music that I could study for an extensive period of time. I tried to just listen to the piece from a musical perspective for a long time. Then I went through it thinking about the structure and counting it out on paper. I sat down with Susan Walters, one of the pianists at NYCB, just to make sure I was upholding the integrity of the piece. I didn’t want to pre-choreograph too much. For me it’s helpful to come up with a few ideas, but then when I get into the studio I often end up doing something completely different. I decided on eleven dancers. Using pennies for men and dimes for women, I started looking at different formations on the stage. I took a bunch of pictures of the coins. Then someone told me that Balanchine did the tattoo of Union Jack with pennies… I chose really fast music and a large group because those are the hardest things you can do.

© Troy Schumacher. (Click image for larger version)

Did you get feedback?

I got a lot of feedback from people who were there, and I was really happy at how positive it was. I hope to get the chance to develop the piece further in the near future.

What do you feel are your greatest strengths at this point?

I think probably my greatest strength is my desire to hear honest criticism. It’s hard to create a ballet, and to get funding; you have to present yourself as someone who is confident. I do all the administrative work and fundraising. I’ve always been interested in what it takes to make the arts happen. And my second greatest strength is my determination to study all these other art forms. I think a musical education is so important and all the best ballets are made by extremely musical people.

And your greatest weakness?

Insecurity. I’m very hard on myself. I have a hundred thoughts going through my head and I put a lot of pressure on myself. But as time goes on it gets much easier. I haven’t made enough ballets to be able to tell if I’m truly good or not. What was fun was having some conversations with other choreographers at the Institute. The classical music community has a nice group of composers, and it would be interesting to have something like that, an honest round-table discussion about ballet and art and community.

You must be logged in to post a comment.