© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Chunky Move

247 Days

Melbourne, Malthouse Theatre

15 March 2013

www.chunkymove.com

www.malthousetheatre.com.au

It is helpful to think of Anouk van Dijk’s second work for Chunky Move, 247 Days, as the next chapter to 2012’s An Act of Now. Like An Act of Now, 247 Days examines isolation and alienation, looking at the challenge of developing a sense of self within a kind of community context. Whereas An Act of Now trapped the dancers in a tiny glass house with the audience sitting outside, 247 Days returns to a traditional theatrical format. However, a set featuring a mirrored wall creates the sense that we are now inside the glass box with the dancers. The perception of the world outside is fragmented by the breaks in the mirrors, bringing to the fore a heightened sense of self-reflection. In the same way that dancers in An Act of Now stared out of the glass windows without ever seeming to see into the audience, the dancers in 247 Days are obsessed with their own appearances in the mirrors. In both works the story is about self.

The question van Dijk seems to be posing with 247 Days concerns how an individual comes to terms with personal change, considering that the evolution of the species is so slow. One of the key physical images of the work has the dancers posing as if in midstep, the upper body gently rotated towards the extended foot, which in turn, is rolled slightly outward. The big toe sticks up, as if in the process of hitting the floor, a movement that does not translate to an expected kind of locomotion.

The paradox of presenting this snapshot, drawn from movement – but presented in a static, unchanging form – is also the key to understanding this work. Things are always different, van Dijk seems to be saying, and yet… nothing ever really changes at all. When we apply this to van Dijk’s own recent relocation from Europe to Australia, this angst about identity and fitting in begins to make sense. Moreover, references in the text to rapidly changing technology suggest that this sense of isolation is exacerbated by the very tools we use to connect to one another.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

247 Days begins with a solo by dancer Lauren Langlois. She is set against designer Michael Hankin’s wall of angled mirrors which create a kind of bowl to reflect multiple images of her body. At times, there is no image at all. Later, the dancers angle the mirrors further, so that their reflections are all we see of their physical selves.

The movement material first presented in Langlois’ solo is explored repeatedly throughout the work, manipulated for a group as they stride across the floor in unison, or adapted as a starting point for contact between performers. The repetition in the movement reflects the fact that these dancers are ultimately stuck in one kind of existence.

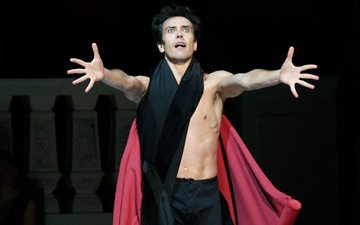

Perhaps van Dijk’s greatest skill as a choreographer is the complexity she brings to contact partnering work. As the dancers make contact, the focus is not the peak of the lift, but rather the whole system of connection that sees dancers wound up and stretched out or drawn together and pushed away with a spectacular moment of falling or flying folded seamlessly into the next sequence. The best example of this in 247 Days is a trio between three men, in which they both resist and accept the vulnerability of giving their physical weight to somebody else.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

van Dijk has been in Australia for less than a year, and already the new Chunky Move has presented two full-length works. The transition of van Dijk’s Chunky Move into an Australian company has begun as well. The dancers that came to Australia with the choreographer (Nina Wollny, for example) and appeared in An Act of Now have been entirely replaced by a local cast.

As a cast they are still relatively new to both van Dijk and Countertechnique, her system of training which seeks to throw the body off its centre of gravity. There are some aspects of this movement language that the dancers are doing beautifully. The fluidity of Langlois’ upper body is matched by the strength of Niharika Senapati’s lower body. James Pham brings a kind of heightened suspension to his interpretation of the movement; this expressiveness is best matched in Leif Helland’s mobile face. However, across the board, there is an unevenness in the performance, particularly in the delivery of the spoken text, which is heavy-handed as often as it is profound. As a layer to Marcel Wierckx’s soundscore (which also features the dancers singing in a kind of echoing, haunting chorus) the use of voice is a masterful texture.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

As I sat there through two performances of 247 Days (and mourning the fact that highly experienced dancer Nina Wollny does not appear in this particular work) I wondered if perhaps this was the same feeling experienced by dance writers nearly a century ago, as they watched a very different company of dancers learn to speak with the physical, and highly idiosyncratic, voice of Martha Graham. It may be a romantic notion (and I do not presume to suggest van Dijk is the Graham of this time and place) but there is something to be said for giving a company time to learn to perform fluently in the same physical language. Already, however, Anouk van Dijk’s Chunky Move is ‘speaking’ with a new inflection, as van Dijk’s Countertechnique takes on the accent of these Australian dancers. They may not be fluent yet, but no doubt it will happen in time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.