© Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

City Center Encores!

On Your Toes

New York, City Center

9 May 2013

www.nycitycenter.org

For all its celebrated confluence of ballet, Broadway and Balanchine, its cheeky book and smashing dance numbers, On Your Toes, the 1936 bauble revived all-too-briefly as part of City Center’s Encores! series, speaks most eloquently with the cynical and sad voice of Lorenz Hart, his arch words set against the contagious tunes of his more-famous collaborator, Richard Rodgers. With barbed wisecracks, songs that seldom mean just what they say, and a denouement in the “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” ballet which merrily takes “the show must go on” to an absurd and near-fatal conclusion, Hart (and perhaps George Abbott, who also worked on the book) encourages you to enjoy the show’s glamor (did I mention there’s a ballerina?), humor and high spirits, but his rapier’s seldom sheathed, and can still prick you over the decades.

In the second act, the hero, Junior Dolan, the hoofer-turned-music-professor played by Shonn Wiley, asks advice on romance from Peggy Porterfield, the socialite d’un certain age who’s bankrolling the Russian Ballet about which the show’s comedy swirls, portrayed with effortless, upper-crust mastery by Christine Baranski. A target for the charms of both his fresh-faced but hardly naive student Frankie Frayne (Kelli Barrett) and the ballerina Vera Baronova (Irina Dvorovenko), Dolan asks if it’s possible for a “good man” to love two women at the same time. With a perfect heartbeat’s pause, Baranski turns her face to the audience, her eyes a double-barreled shotgun of sang-froid. “If he’s very good,” she drawls. BLAM! In serving his own masters, Hart was very, very good.

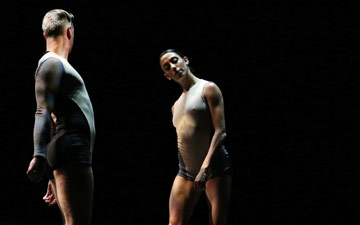

© Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

On Your Toes’ plot, such that it is, concerns Phil “Junior” Dolan III, the tap-dancing heir to a renowned family of vaudeville hoofers. He gives up the stage for college, and becomes a professor shorthair teaching high-brow music to the youth of America at Knickerbocker University. Determined that an American composition should achieve recognition on the high-art stage, he uses Frayne’s social connection to Porterfield to encourage the Russian Ballet to produce “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” written by yet another of his talented charges and, as they say, hilarity ensues. Junior becomes the object of Baronova’s affections, mostly to inflame the jealousy of her partner and sometimes-love, Konstantine Morrossine (Joaquin de Luz), and gets shanghaied into filling in for an indisposed dancer in the “Princess Zenobia” ballet (Scheherezade’s poorer cousin). When Morrossine proves impervious to “Slaughter’s” jazzier rhythms, Junior, his dancing pedigree revealed, takes over the lead, with Baronova. Not surprisingly, Morrossine objects, and hires gangsters to arrange Junior’s onstage assassination during the “Slaughter” ballet, the imaginative foiling of which leads to On Your Toes’ happy, if improbable, conclusion.

Along the way, the show strings together some memorably ravishing songs and knock-out dance numbers while having fun contrasting the straightforward exuberance of Junior and his American college kids with the Russian Ballet’s suspect old-world and high-society sophistication. Soon after we’re introduced to Porterfield and the ballet’s director, Sergei Alexandrovitch (the broadly hammy Walter Robbie), they sing, in “Too Good for the Average Man,” of the perquisites of their stations in life, extolling the virtues of plastic surgery (“cutting off your face to spite your nose”), birth control and even, ahem, abortion (“the modus operandi” which is “quite too good for the average rabbit”), and Baronova and Morrossine are over-the-top caricatures of the louche and vain. In “The Heart is Quicker than the Eye,” Baranski’s Porterfield explains to Wiley’s Junior that, when it comes to love, “there’s no use asking why.”

© Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

Yet, despite the snappier tunes of the college crowd, there’s also snark that speaks more of the Algonquin Round Table than the soda fountain. In “It’s Got to be Love,” love is “that sinking feeling” that’s left after you’ve dismissed other conditions with depressing symptoms: tonsillitis, bronchitis, fallen arches, the morning after, death, etc. Later, stymied in her love for Junior by Baronova’s machinations, Frayne sings of how love makes her “Glad to be Unhappy.” Oh, these kids today. These are all marvelous songs, but they make one wonder just what Hart had against love. In the one straightforward love song, “There’s a Small Hotel,” (“with a wishing well”) Hart describes a honeymoon spot so cloyingly idyllic you can practically see him rolling his eyes as he penned the words. And while the title of the rousing “On Your Toes” number provides the double-entendre necessary to remind us that there is, indeed, ballet in this show, it’s also a paean to social climbing that’s almost Gatsbyesque: plucking the best fruit from the top of the tree (for which “you’ve got to be up on your toes”) is just like landing oneself in a more desirable neighborhood, like Chelsea or Sutton Place.

It’s a tribute to Rodger’s melodies and Hart’s wit and way with a rhyme that the show’s more outstanding for its comedy and verve than the cynicism that, like a shark, is never far below the surface. It’s really not surprising that, for the 1983 Broadway revival, George Abbott changed a line in “Questions and Answers (The Three B’s),” to assert, however anachronistically, “you will never get the old diploma here/if they catch you singing Oklahoma here,” a reminder, as if we needed one, that Rodgers and Hart were a far cry from Rodgers and Hammerstein. (The original line is about “whistling La Paloma here,” which may have meant something in 1936, but doesn’t even inspire me to hit Google today.) (I also miss a line from ’83 when a gangster, wandering backstage, says something to the effect of “Merde, merde, merde. What’s this merde everyone keeps talking about?”)

And think about the irony of “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue’s” climactic moments. After Junior’s Hoofer has his romantic duet with Baronova’s Strip Tease Girl in the ballet’s cheerily colorful speakeasy, she’s shot trying to protect him from the pimpish Big Boss (subtle, this story’s not). He shoots the boss, then, in grief, he’s about to do the same to himself, but then Junior’s warned that there’s a hit man in the audience waiting to shoot him for real when his character commits suicide. This leads Junior to forestall that final moment with encore after encore of his last exhausting steps until after the mobster’s safely apprehended. It’s great fun to see Junior’s increasing desperation with each repeat, but surely in such a situation it would make more sense to run into the wings (or for someone to drop the curtain). Of course a trouper like Junior wouldn’t consider for an instant anything that would stop the show, and, at this point, neither would we. Anything other than his cry of “One more time!” to the conductor would be anticlimax, and no way is this roller coaster going off the rails so close to the big finish.

With the excellent Encores! orchestra on a raised platform taking up much of the upstage half of City Center’s stage, Warren Carlyle, the director and choreographer, must stage his action along a narrowish front section. (Encores! productions are usually costumed, but, for economy, only use the sketchiest of sets and props.) For the most part, he handles this ably, with his pared-down staging of the big “On Your Toes” number making clever virtue of this necessity. However, characters are often called on to make lengthy entrances and exits in full view along a strip of catwalk at the front of the orchestra’s platform, which may have contributed to Dvorovenko’s almost cartoonishly broad portrayal of Baronova (or this may just be her familiar portrayal of every heroine as Kitri, transformed to this slightly different medium). Probably at Carlyle’s behest, she makes the most of these extended upstagings, often while her character’s in a snit, waving her arms dramatically about her head as she exits in a flounce of fabric wafting about her person, as if fending off an attack of the vapors, or perhaps becoming Isadora in search of a Bugatti. It’s a funny caricature, but wears thin with repetition, and I don’t remember Natalia Makarova carrying on so in Abbott’s production thirty years ago, but that had the benefit of a more traditional stage and staging.

© Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

I also don’t recall Makarova looking as if she could gut you with her shoulder; the thinspo glamor of Dvorovenko’s super-attenuated physique (she’s damn thin) is even more striking when sheathed in a wispy dress (from costume consultant Amy Clark) than a more constructed classical tutu (as she affects in “Princess Zenobia”). With the similarly expressed beauty of her features — sharply etched eyebrows and cheekbones, and a forehead of consequence — she presents herself as a Force to be Reckoned With, much as on the ballet stage. Indeed, the lively animation so well suited for projecting to the Met’s cheap seats and beyond makes short work of Baronova’s vanity and jealousy. She gives the diminutive De Luz’s Morrossine an eye-rolling once-over before, in a Russian accent so thick you could cut it with a sickle, pronouncing him a “two-inch liar” for his use of heel lifts, and then, dismissively turning her back, as such a liar “everywhere.”

For all of Dvorovenko’s effusive ballerina-ness, her comedic timing isn’t always perfect, and sometimes a line delivered too quickly and emphatically didn’t get all the laughs it might have. Similarly, her Strip Tease Girl was emphatic indeed, including the grindiest bump-and-grind I’ve seen in any production of “Slaughter,” although she may simply been using the wispy scarf/skirt she’d removed from her waist to demonstrate a post-shower toweling technique for getting one’s hips really, really dry.

As Morrossine, De Luz was an appropriate foil for Dvorovenko, managing his stage accent perfectly, and partnering her in Princess Zenobia with such aplomb you’d hardly notice she seems to loom a good head taller than him when she’s on pointe. He even had a few moments to demonstrate his considerable bravura.

Perhaps one day I’ll see a production of On Your Toes with a truly charismatic Junior, but it hasn’t happened yet. It’s a tricky role, for as a music teacher he must be the epitome of the nerdy band geeks we might remember from high school, yet with enough charisma so we understand why Frayne falls for him, and Baronova affects to. He must be hilariously and believably inept and chaotic as the unrehearsed, not-quite-dyed-in-the-wool slave in “Princess Zenobia,” while emerging from this sad chrysalis as the romantic lead and bravura, jazzy Hoofer in “Slaughter.” Lara Teeter didn’t quite manage it thirty years ago, and Wiley doesn’t quite now. He’s a stiff professor and unsure lover, even after his schooling by Baranski, although a good enough singer and tapper to carry his role. Unfortunately, in “Slaughter” he had little chemistry with Dvorovenko, holding her as if afraid one of them would break, and coming to life only in the frantic wildness of his life-preserving encores. In 1936, Ray Bolger was the original Junior, and perhaps only a performer of his charisma and brilliance could really pull it off. (Balanchine’s said to have once called Bolger the best male dancer he’d ever worked with — probably when within earshot of Villella or Baryshnikov.)

With this odd lack of weight at the show’s center, supporting characters can rush in. Kelli Barrett’s a fine, if slightly brassy, Frankie Frayne, although we never really see why she loves Junior (or he, her, for that matter). As Alexandrovitch, Walter Robbie’s properly old-worldly and avuncular, and beautifully introduces “Quiet Night,” perhaps the show’s only song that’s as sincere as it is lovely. In her brief appearance as Lil Dolan, Junior’s mother (with Dalton Harrod as the young Junior, and Randy Skinner as his father), the great and ebullient Karen Ziemba gave a seminar in scene stealing, an education continued by Baranski, the show’s true star. It’s not just her timing that makes her so, but the apparent ease with which she floats through the show, as if commanding our attention here was an amusing lark. That by the end of the show which she so effortlessly steals, she looks to have neither sweat or perspired a drop speaks as much of her character’s moneyed security as it does her seemingly artless perfection, at once magisterial and laid back.

© Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

Despite my above reservations, when it came to the big numbers, the show, and Carlyle’s staging, delivered. The orchestra popped jauntily through “On Your Toes” and “Slaughter,” under guest conductor Rob Fischer. For “On Your Toes,” Carlyle deployed his dancers carefully through his limited space to make the effect of a huge production number, with dancers moving about and hopping on and off some ubiquitous benches to create ever-shifting perspectives, although I missed the knock-down competition between ballet and tap of Saddler’s 1983 choreography. Carlyle made it amply clear he had a lot of terrific dancers of both disciplines to work with, and I can’t say enough good things about the energy of this ensemble.

I’m a little puzzled by Amy Clark’s decision to present the Russian Ballet’s dancers here not in the smocks, dresses and tunics one might expect from the period, but the full Balanchine: super-tidy “practice clothes.” With their white tee shirts and gray tights, the men looked ] ready to launch into Square Dance, more ambassadors from the NYCB of the future than representatives of the Diaghilev era’s fading glory. Was it carelessness, or a sly tribute to Mr. B?

Speaking of whom, I liked Susan Pilarre’s carefully detailed staging of “Slaughter,” right down to the hand of the dead Big Boss seemingly clutching at Junior from beyond the grave. The choreography worked surprisingly well in the shallow stage area, and if Dvorovenko and Wiley didn’t exactly set the stage on fire, it hardly mattered by the glorious finale (although to this day I wonder why Morrossine didn’t follow his gangster pals to jail instead of rejoining Baronova). I hope I don’t have to wait another thirty years to see this show one more time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.