© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Raven Girl, Symphony in C

London, Royal Opera House

24 May 2013

Dave Morgan: small gallery of Raven Girl and Symphony in C pictures

www.roh.org.uk

Wayne McGregor proposes that his Raven Girl is more visual theatre than narrative ballet. (It’s invisible theatre for many Opera House viewers, alas, thanks to a scrim at the front of the stage and gloomy lighting.) He and his collaborators have created a dark 72 minute fable, based on a graphic novella commissioned from Audrey Niffenegger. She etched the images in her story book and wrote the spare, gothic text. McGregor has animated the fantastic tale with dancers, aided by a design team he has used in the past: Ravi Deepres, film projections; Vicki Mortimer, set and costumes; Lucy Carter, lighting design with Simon Bennison. The score is by film composer Gabriel Yared.

Together, they have imagined a surreal dreamscape in which a human mates with a female bird, producing a hybrid raven-maiden. Like Odette, she’s not happy with her half-avian situation and needs a prince to come to her rescue. So far, a familiar balletic fairy tale – except that this one requires mutilation rather than transformation. While Odette is a woman (by night) who hates being a swan by day, Raven Girl so longs for wings that she voluntarily has her arms cut off. It’s a horror story,in part a cautionary tale about the futility of plastic surgery as solution to feelings of otherness.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013.

The ballet begins with a laborious exposition in which a simple postman (Edward Watson) sorts and delivers mail. He finds and adopts a fledgling raven, whom he marries. Here McGregor has to deal with a tricky choreographic problem: how to simulate a real bird’s movements. Olivia Cowley, face covered by a mask as the Raven, stands pigeon-toed, bum stuck out as birds do; only when she is supported in lifts can her legs fly like wings. Perched on a bedstead, she gives birth to an egg.

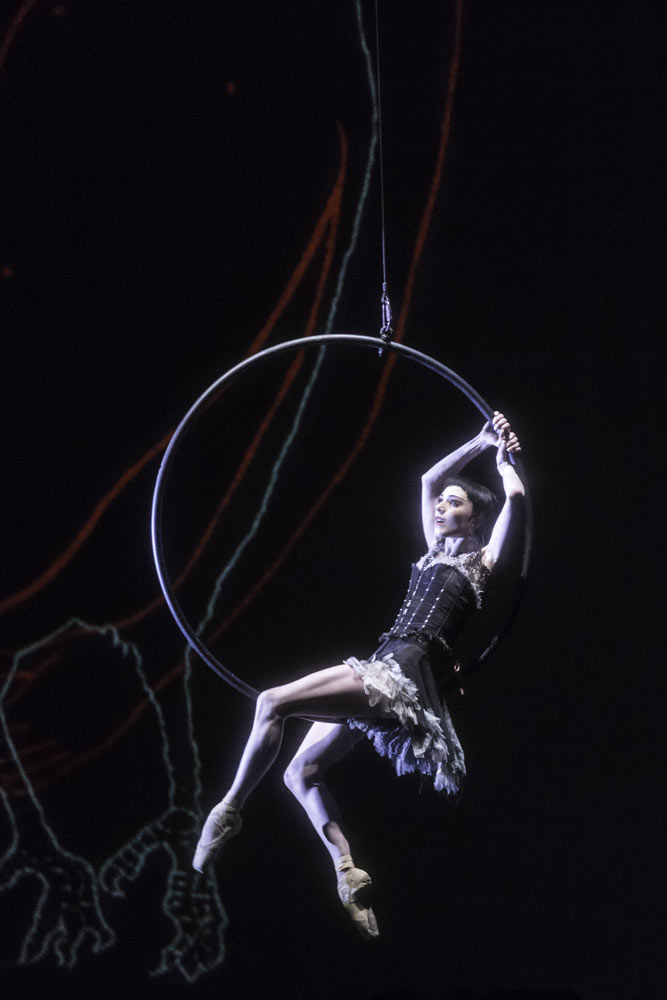

Out of it comes Sarah Lamb as the Raven Girl, lithe and lovely unlike her ungainly mother. But she can’t communicate, except by silent squawks, and she can’t fly. Her only way to achieve weightlessness is to swing and swirl on a metal ring. Lamb is pale and poignant as the frustrated girl, watched by her puzzled parents. Their roles remain two-dimensional, with just a brief solo for Watson to imply he’s no ordinary postal worker.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013.

Raven Girl is packed off to university in a strange town peopled by faceless commuters – shades of McGregor’s Infra, with its marching LED figures. Stumbling urban dwellers are contrasted with free-wheeling birds, both as filmed projections and as a corps conspiracy of ravens. McGregor’s ingenuity falters whenever he tries to deal with birds en masse: all the corps de ballet does is pace in triplets, one, two, three, arms flapping. You can see (if you can see) that he’s aiming for a sinister flocking effect but the birds’ choreography is as basic as a ballet for children.

It’s a relief when Paul Kay appears as the Boy who is attracted to the lonely, out-of-place Raven Girl. He has a dynamic solo, offering her paper wings and demonstrating his sympathetic understanding of her desire to defy gravity and spin deliriously. At last, a character expresses human feelings through the medium of dance. Yared’s music, eerily atmospheric until now (a mix of electronics and orchestral instruments) erupts into rhythmic energy.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013.

But Raven Girl is interested only in a visiting professor of evolutionary biology. We know his profession from projected slides and living examples of chimeras – mismatched creatures who twitch in typical McGregor contortions. Raven Girl persuades the Frankenstein doctor (Thiago Soares) to replace her arms with prosthetic wings. In a gory sequence – the only colour in the monochrome ballet – he does so, watched by the horrified boy. Though the stormy staging is spectacular, it’s almost impossible to tell at a first viewing what the mad doctor has achieved.

Is the transplant a success? Is Raven Girl happy as she flails her metallic wings in arabesques? Probably not. Can she fly? Probably not, if the story is to make any sense at all. Boy kills doctor, girl mourns, mother removes her daughter’s wings, presumably rendering her armless. So the experiment, the climax of the ballet, has been a disaster.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

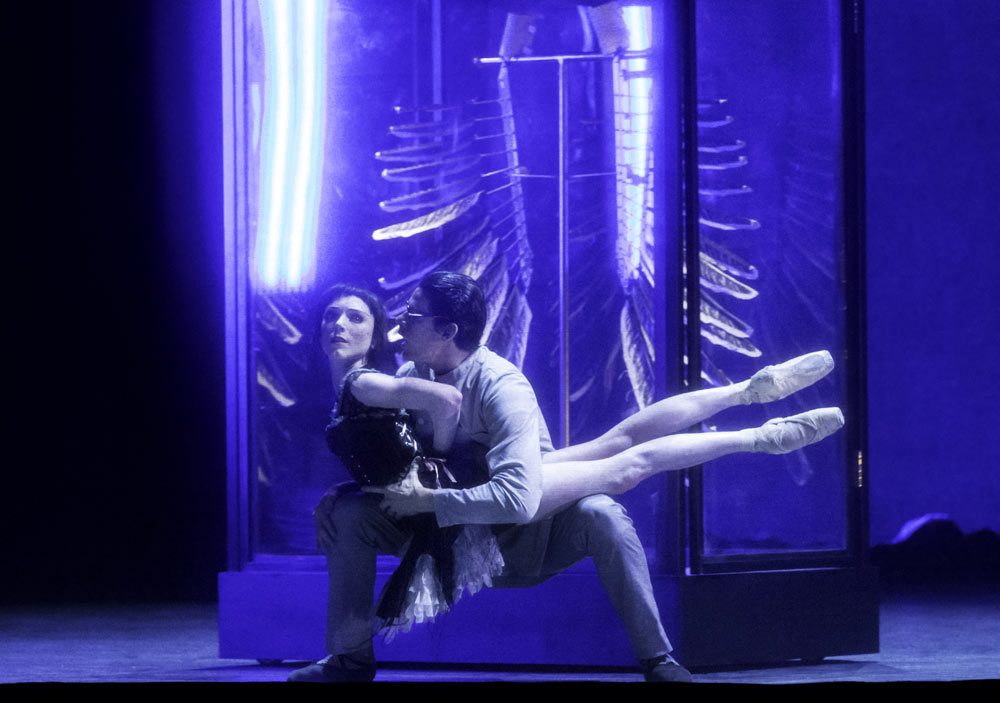

But this is a fairy story after all, however noir. Somehow or other, for the final scene, Raven Girl is retrieved by a Raven Prince (Eric Underwood), who comes down from a cliff at the side of the set. The Boy has previously gone up it, so maybe he’s been transformed into the saviour prince. Or not? There’s nothing avian about Underwood, apart from the length of his arms. Lamb flies into them, the strings in the orchestration describing thrilling bliss. Manipulated by Underwood, Lamb’s limbs seem as light-boned as a bird’s, as flexible as feathers. The balletic metaphors for flight in this acrobatic pas de deux make a satisfactorily happy ending: the couple, who have kissed as humans, walk hand in hand up the cliff into the hereafter. A blizzard of letters descends on the postman below. Maybe the whole thing was just his dream.

A dream would seem a plausible pretext for a ballet whose scenes don’t cohere and whose schematic characters don’t develop. McGregor has translated Niffenegger’s dark imaginings from page to stage in a faux-naif fashion, relying on projected captions to keep the story going. Deepres’s animations of ominous black birds are far more evocative of an alternative state of being than anything McGregor can suggest in dance – especially for the corps de ballet of ravens. Lamb gives the Raven Girl a febrile intensity without being able to make us suffer her sense of being trapped in an alien body, since her choreography is unrevealing. We don’t know, for example, what she feels about her beautiful transplanted wings; we realise she has to lose them to be able to dance the ecstatic final pas de deux.

At this stage, Raven Girl seems a work in transition. Its longueurs need tightening, an inexplicable ‘19th century couple’excised, solos for important characters expanded, and more light thrown on the goings-on.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

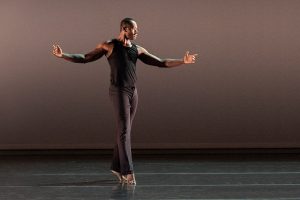

In the second half of the programme, Balanchine’s Symphony in C is clarity itself. The Royal Ballet’s tendency to dance Balanchine too daintily was offset by the boldness of Zenaida Yanowsky and her prince of a partner, Ryoichi Hirano, in the first movement, and by Marianela Nunez and Thiago Soares in the sublime adagio. Nunez has learnt to soften her superb technique so that she seems to need an adoring partner to assist her, instead of being a gloriously self-sufficient ballerina. And what an effective applause machine the last movement is, everyone in the air at the same time – thank you!

© Bill Cooper, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Jann Parry cogently reads more into Raven Girl than is immediately evident on stage. McGregor does not deign to do anything so obvious as tell a story. He has disingenuously moved the goal posts – rather than extending the playing field –

by claiming this is visual theatre. Is not all theatre visual?

Lucy Carter’s magical lighting is usually the star of McGregor’s ballets. Here she tactfully cloaks proceedings in murk. McGregor works again with a favoured few dancers rather than the full resources of The Royal Ballet. The vast space of the Covent Garden stage is also under exploited. McGregor’s knowledge of ballet is self-admittedly patchy – but should he be interested to learn, he need look no further than the accompanying balletic geometry of Symphony in C. (Sarah Lamb with crystalline brilliance showing how Balanchine really looks).

Raven Girl is long haul in economy class – but the promise of the closing pas de deux kept me tantalised. But the journey there had no sense of pace, no tension, no character, no sense of theatre – no narrative. There some incidental pleasures – the boy made something individual by Alexander Campbell – and the round window from Playschool gave Melissa Hamilton some circling acrobatics.

When we finally reached the joyous closing duet for the prince and the girl, the choreography could have come from any of Christopher Wheeldon’s ballets. How perverse of me to miss McGregor’s usual extreme, hyper tensile couplings.

Raven Girl is a self-indulgent. I question the director’s role when new work arrives onstage in so raw a form. The pattern here is a worrying one.