© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

Slava Samodurov: bringing Yekaterinburg Ballet in from the cold

Regular DanceTabs contributor, Graham Watts, braved 21 hours of flights, a missed connection and 10 hours stuck in Moscow’s packed Domodedovo airport just to spend a night at the Yekaterinburg Opera House followed by a meeting with its new(ish) Director of Ballet, Slava Samodurov, a former Principal at The Royal Ballet.

It was -26°centigrade when I stepped from an aeroplane in the early dawn of a Saturday morning onto the snow-covered tarmac of Yekaterinburg airport. 26 degrees below freezing was a new definition of cold for me and although my clothing just about managed to cope, the dry air stung my face and ears. More perilous was an ongoing struggle to stay upright on the ice rink that covered this Russian city sheltering to the east of the Ural Mountains, near to the Eurasian border (over one thousand miles from Moscow). It seems, however, that I was fortunate, since winter temperatures here can fall as low as -45°!

Yekaterinburg (often translated as Ekaterinburg) is a city that will forever be known for the murders of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, Alexandra, their five children and loyal staff in July 1918. The Ipatiev Mansion, where these assassinations took place, was demolished on the orders of Boris Yeltsin (then governor of the Ural Region) in 1977, and in its place stands an imposing, beautiful white cathedral, topped by golden domes (called the Church of the Blood), ironically commissioned by Yeltsin after becoming Russian President. Several kilometres outside the city, a tranquil monastery comprising seven simple wooden churches, one for each of the murdered Romanovs, stands in a forest of silver birch trees marking the site of ancient mining shafts where the Imperial family’s remains were found by archaeologists in two separate discoveries, sixteen years’ apart (1991/2007).

Yekaterinburg (often translated as Ekaterinburg) is a city that will forever be known for the murders of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, Alexandra, their five children and loyal staff in July 1918. The Ipatiev Mansion, where these assassinations took place, was demolished on the orders of Boris Yeltsin (then governor of the Ural Region) in 1977, and in its place stands an imposing, beautiful white cathedral, topped by golden domes (called the Church of the Blood), ironically commissioned by Yeltsin after becoming Russian President. Several kilometres outside the city, a tranquil monastery comprising seven simple wooden churches, one for each of the murdered Romanovs, stands in a forest of silver birch trees marking the site of ancient mining shafts where the Imperial family’s remains were found by archaeologists in two separate discoveries, sixteen years’ apart (1991/2007).

© Yekaterinburg Opera and Ballet Theatre.

Both the Church and the Monastery are now places of extraordinary devotion and – even with temperatures as low as they were – people queued to pay their respects, including many who were profoundly disabled, clearly seeking a miracle from the artefacts and icons that they were patiently waiting to kiss or touch. It would appear that, thanks to its notorious history, Yekaterinburg is now Russia’s equivalent to Lourdes.

And a miraculous transformation is being wrought upon the city’s ballet company. The Ural Opera House is an opalescent gem of late Imperial architecture, which celebrated its Centenary last year, meaning that it is itself a silent witness to the tragic events that occurred just six years after it was built. Formally known as the Yekaterinburg State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre, it has long been a centre for elite opera, winning several awards and accolades down the years. It was apparently the first opera house outside Moscow or Leningrad to win the Stalin Prize (for its staging of Verdi’s Otello in 1946), a significant cultural achievement repeated in 1987 when it won the State Prize again (the Stalin title having been terminated) for The Prophet by local composer, Vladimir Kobyakin.

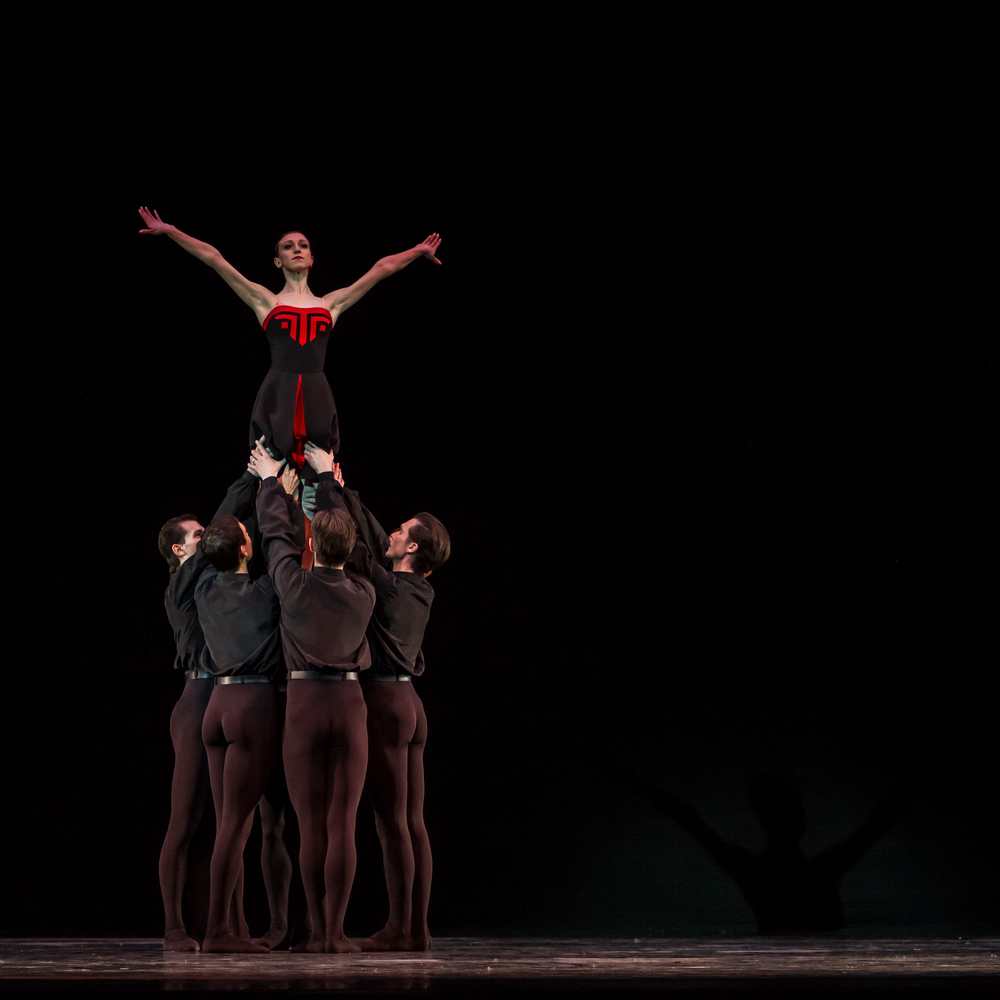

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

By coincidence, the night of my arrival in Yekaterinburg was marked by yet more prizes as the Theatre’s Director, Andrey Shiskin, received three awards from the newspaper Muzykalnoye Obozreniye (a leading Russian cultural journal), including Arts Personality of the Year for Shiskin himself to mark the theatre’s outstanding development under his management. Two other awards were for operas performed during the Centenary Season (Rossini’s Le Comte Ory directed by Igor Ushakov and Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov directed by Alexander Titel).

It was Mr Shiskin’s adroit vision that attracted former Royal Ballet Principal, Viacheslav (Slava) Samodurov, to come and direct the ballet company, succeeding Nadezda Malygina for the 2011/12 season. His first full-length ballet, Amore Buffo – a modern romantic comedy to Gaetano Donizetti’s music for the opera L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love) – has received considerable critical acclaim in Russia, evidenced by the signal honour of the Yekaterinburg Ballet being invited to open the dance section of the prestigious Golden Mask Festival at the Bolshoi Theatre in February.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

Amore Buffo was a contender for the Best Ballet production, won by Diana Vishneva’s Dialogs for the Mariinsky (Nacho Duato’s Multiplicity. Forms of Silence and Emptiness, recently seen in London during the Mikhailovsky Ballet’s tour, was another nominee). In fact, Amore Buffo was the only production to garner nominations in every ballet category: for best conductor (Pavel Klinichev), best choreographer (Samodurov), best female dancer (Elena Vorobyova) and best male dancer (Andrey Sorokin). Although it didn’t succeed in any of these categories at the awards ceremony in Moscow – held on 16 April – the Yekaterinburg Opera House did win two Golden Masks: one, again, for Le Comte Ory but the other significantly as a “breakthrough” award (equivalent to “Best Emerging Company of 2012”). There is no doubt that the significant achievements of Samodurov’s first season-and-a-half had some bearing on this welcome recognition.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

I arrived in Yekaterinburg to catch the premiere of his first triple bill, always a huge challenge for any director in terms of balance and programming for audience appeal. But there was no playing safe for Slava since his selection was adventurously diverse. Under the enigmatic title of XIX – XX – XXI he pulled together three ballets made in separate centuries, demonstrating the development of the art of choreography in Northern Europe over a vista of some 200 years. “I concentrated on northern European styles because I wanted to create a journey through ballet epochs while remaining within a geographical boundary that would be understood by a Russian audience”, Samodurov told me over a cup coffee on the morning after the premiere.

From the nineteenth century he chose August Bournonville’s Le Conservatoire (or more accurately its first act), created by the Danish master in 1849 to represent a dance class as attended by Bournonville during his time studying with Auguste Vestris in the 1820s. While he cannot be absolutely certain, Samodurov has found no evidence of either the complete ballet or this one-act extract ever having been performed in Russia before and Dinna Bjørn, the consultant advising on this restaging, was also unaware of a precedent in living memory. Given her credentials as former artistic director of both the Norwegian and Finnish National Ballets and long-time dancer and artistic advisor on Bournonville’s choreography at the Royal Danish Ballet, she ought to know!

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

Samodurov’s choice of Five Tangos (made in 1977) to represent the twentieth century was equally pioneering since he is sure that no work by Hans van Manen had ever previously been performed by a Russian company. This struck me as surprising, perhaps because van Manen’s work was so beloved by one particular Russian émigré, namely Rudolf Nureyev. If anyone is aware of a van Manen piece ever previously being taken into the repertoire of a Russian company, “answers on a postcard, please”!

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

And finally, the current century was represented by the world premiere of a new work by Samodurov himself, entitled Cantus Arcticus, made to a score by the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara and sub-titled Concerto for Birds and Orchestra, which was a work without narrative but one that seemed to be inspired – at least in part – by a quest for the Aurora Borealis (The “Northern Lights”). This particular emphasis on the north exemplified a programme of work from Danish, Dutch and Russian choreographers.

At first glance such a diverse programme seems as if it may be a fragmentation too far but Slava explained his motivation by saying, “I wanted to challenge my dancers and involve as many as possible in a programme that would stretch them by testing their strength and abilities”. He added, “It’s crucial for dancers to encounter new choreographies and styles; and the only way that they can progress. Without these big challenges, the dancer’s life is like running in circles. It brings little benefit to anyone”.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

The other incentive was to boost the reputation of the company within Russia: “Becoming the first Russian ballet company to dance van Manen choreography puts us in a strong position”, Samodurov told me, adding: “Essentially, we are putting something new into the Russian ballet club”. This certainly seemed to be evidenced by the fact that several dance critics had taken the long flight from Moscow to review the show.

The risks of such a programme, however, are also significant. “Bournonville and van Manen demand immaculate precision and clarity”, Samodurov explains. “They require another type of stage presentation: it is less in your face, more subtle but this doesn’t mean it is any less energetic or powerful”, he asserts. “The key is that these are different ways of dancing for Russian ballet dancers and very new ways of expressing themselves on stage. They are both very difficult ballets to perform and I see them as important stepping stones in the further development of the company”.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

In truth, the company struggled with the precision and filigree neatness of the Bournonville style, especially in the male soloist roles. Some men seemed too bulky in the thighs to deliver the fleet, lightness of jump required although one could detect the impact of working directly with Bjørn. She appeared pleased with their first effort at Bournonville, particularly in the close harmonies of the corps de ballet, the neat style of the lead ballerinas (two Elenas, Trubetskova and Soboleva) and the considerable stage presence of the leading dancers. The Yekaterinburg Ballet does not yet have a school of its own (although Samodurov has plans) and pupils of a local ballet “Lyceum” (named after Diaghilev) charmingly made up the younger members of the conservatoire class.

I had no reservations about an excellent performance of van Manen’s Five Tangos, which was coached by Mea Venema and Alexander Zhembrovsky, both of whom had come from the Dutch National Ballet for the purpose. This was the only work performed to a recorded soundtrack (Astor Piazzolla’s Argentine music) and – with recent performances by Scottish Ballet freshly in mind – I felt that the whole ensemble achieved a refreshing alacrity in handling both the competing tensions between spiky movement and cool twists and the punctuated “stop-start” choreography against the smooth musical flow. Several of the duets were especially impressive and particular mention goes to the excellent flourish and rhythmic precision of Elena Kabanova, Andrey Sorokin and Larissa Lyushina.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

Samodurov’s own new work continued the impressive rich vein of neoclassical abstraction that hallmarks his choreography. Cantus Arcticus was conceptually dominated by two elements. Firstly, the remarkable naturalism of Rautavaara’s three-part score, probably his best-known piece, composed in 1972; and then the effective transparent wall, conceived by Samodurov’s regular set designer, Anthony MacIlwaine. This structural centrepiece comprised curtained layers of Perspex, through which dancers passed, their ephemeral reflections, adding a mystical quality to Samodurov’s choreography. Amongst the ensemble of dancers, I was once again impressed by the pairing of Sorokin and Lyushina (both of whom made such an impact in the TV Kultura Bolshoi Ballet Contest, held late last year) and they were joined by yet another talented Elena (Vorobyova – the other Golden Mask nominee alongside Sorokin). These three very talented and charismatic lead principals could take their place in the upper echelons of any company world-wide.

Having very successfully negotiated the two critical hurdles of a first full-length ballet and triple bill, Samodurov is now planning a further triple bill under the title En Pointe for late June, which will include a world premiere (Eventual Progress) by Jonathan Watkins to a new orchestration of Water Dances by Michael Nyman. Watkins was in Yekaterinburg to begin the creative process and select his dancers while I was there. Before this comes to fruition, there is another season of XIX-XX-XXI plus performances of Don Quixote, Andrei Petrov’s 3-Act ballet Creation of the World, Swan Lake, Romeo & Juliet, and The Stone Flower (all to come in May) and then another run of Amore Buffo, Swan Lake, La Sylphide and Giselle earlier in June. It’s a busy company and as if running it is not enough Samodurov himself is already committed to making his own Romeo and Juliet for the Royal Ballet Flanders, due to premiere on 13 February 2014 at the Ghent Opera House. While it is too early to say what Slava’s vision of Prokofiev’s much-used music will be, I think we can count on a ballet replete with neoclassicism that will aim to be both traditional and imaginative.

© Sergei Gutnik. (Click image for larger version)

As to Samodurov’s future plans, well bearing in mind the unique history of the city in which his ballet company is based – and with an important Centenary on the horizon – I would not be surprised to learn that Deborah MacMillan’s telephone rings with a request to set her late husband’s Anastasia on a new company. It seems like an event waiting to happen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.