www.hodsonarcher.com

www.uncsa.edu

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeux

Book: ‘Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet: Reconstruction of the Dance and Design for Jeux‘ by Millicent Hodson

Games People Play: Jeux Young at 100

[aside]Hodson & Archer Links

[/aside] [aside] www.hodsonarcher.com[/aside] [aside] La Création du Monde – A Post-War Cubist Collage Returns to the Stage

about Hodson & Archer’s re-creation of an original Ballets Suédois work.

[/aside] [aside] Thoughts on Le Chant du Rossignol

documentary on Hodson & Archer’s reconstruction of a lost Ballets Russes work.

[/aside] [aside] ‘Reading the Riot Act‘

Archer and Hodson on the Ups & Downs of a TV Docudrama on The Rite of Spring (February 2006)

[/aside] [aside] ‘Sacre in Kobe‘

Hans Rinderknecht’s diary and photographs of seeing Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer put Sacre on in Japan (Autumn 2005)

[/aside] [aside] ‘Seven Days from Several Months at the Mariinsky‘

In 2003 Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson kept a diary for Ballet.co during their staging of The Rite of Spring with the Kirov in St Petersburg.

[/aside] [aside] From 2002

Millicent Hodson Interview

[/aside]

The centenary of The Rite of Spring is a world-wide celebration with performances, exhibitions and conferences in abundance. Many people do not realize that 2013 is also the 100-year bench mark for another Ballets Russes groundbreaker – Jeux – likewise choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky. He wrote the scenario as well for the now-acclaimed score that Sergei Diaghilev commissioned from Claude Debussy. The ballet premiered quietly at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées two weeks before The Rite took Paris by storm. Jeux confronted more taboos than any ballet before, and few since, but its transgressions were subtle enough to slip past the public and press almost unnoticed.

Jeux notched up a number of firsts, not least that Nijinsky was the first choreographer in history to devise the scenario for a ballet from his own imagination instead of from an existing story or an actual incident. Among other breakthroughs was the fact that Jeux was the first ballet about life in its own time, and especially about youth culture. Nijinsky himself danced the lead, aged 24, in a trio with his famous partner, Tamara Karsavina, aged 28, and another Imperial Russian dancer, Ludmilla Schollar, aged 25, all three cherished by audiences for how they danced Mikhail Fokine’s choreography. For the centenary we staged Jeux in the USA with the youngest-ever cast of the reconstructed ballet, the dancers ranging from 17 to 20. Our premiere for Verona Ballet in 1996 had boasted a cast of seasoned world-class soloists: La Scala’s Carla Fracci, the Joffrey’s Beatriz Rodriquez and Alessandro Molin from English National Ballet and Aterballetto. At the Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, in 2000 we had another dream team, the brilliant principals Deborah Bull, Bruce Sansom and Gillian Revie, each into their 30‘s, at their peak, already contemplating career changes from dancing to directing. Vintage casting prevailed for productions from 2001 to 2009 at the Rome Opera and at the Joffrey in Chicago. Now, for the first time, we had teenagers.

Jeux in the American South, 2012-2013

We did Jeux in April at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts (UNCSA), “the conservatory of the South,” as it is called by Chancellor John Mauceri, a conductor distinguished by many awards for work with Leonard Bernstein, the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra which was created for him and opera companies worldwide. He has been a Debussy specialist since his years at Yale. The Jeux project at UNCSA was his idea. At the nearby campus of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, epicentre of the centenary storm, Carolina Performing Arts, directed by Emil Kang, was mounting a year-long festival, The Rite of Spring at 100. Mauceri proposed a Ballets Russes evening by UNCSA to close this international event that had opened in September with Valery Gergiev and St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Orchestra. The UNCSA programme included Shen Wei’s Rite of Spring, an animation of The Afternoon of a Faun, a new version of Polovtsian Dances by Susan Jaffe, the American Ballet Theatre star who is now Dean of Dance at UNCSA, plus our reconstruction of Jeux after Nijinsky. The project turned out to be a true collaboration, finessed by UNCSA’S producer, Katharine Laidlaw.

At the end of August 2012 we went for a week to the campus at Winston-Salem to audition student dancers for Jeux. Ninety presented themselves that hot Sunday afternoon, lined up along the barres in a huge studio, numbers pinned to their chests. How to find, in this crowd of hopeful young bodies, the trio that would create the elusive chemistry of Jeux? Millicent called forward small groups to try phrases of the reconstructed choreography, including racquet swings for the men. Then she asked the ballet master, Frank Smith, to lead a combination that challenged the dancers’ ability to maintain Nijinsky postures at breakneck speed. We sat back and scanned the studio for signs of special aptitude. Finally we put together six trios made up of two women and one man. We had them advance toward us, as though walking a fashion ramp, so that we could visualise them in Jeux. To conclude, in an adjacent studio Kenneth gave a short lecture with slides, immersing all the dancers in images from the original ballet. The lights were lower, the air was cooler, everyone calmed down, looked and listened. At the end we named the nine finalists who were to report for rehearsal.

A Mathematical Gentleman and his Geometrical Relations

That week we established who would partner whom and sketched the choreography for about half the ballet. We also gave each dancer a booklet of readings about Nijinsky, Jeux and Bloomsbury, the famous enclave in pre-World War I London where the ballet had been conceived. UNCSA provides an academic as well as artistic education for high school and college students, all of them on scholarship as proto-professionals committed to a career in the theatre. Alex Ewing, a former Chancellor, known to us as a founder of the Joffrey Ballet, explained that UNSCA students “wouldn’t be here if they weren’t good already.” At the end of each orientation rehearsal we all stretched out on the floor for a mini-seminar about what the dancers were reading. Generally, though, we tried to keep the dialogue going while setting the steps so that interpretation, moving with meaning, became second nature. By the end of this initial week the trio that took precedence over the others included Anthony Sigler, just 20, a college sophomore, Shelby Finnie, 18, a high school senior and Clara Superfine, 17, a high school junior.

![The racquet arch at [34] in the orchestra score in the reconstructed Jeux with Shelby Finnie as Schollar, Anthony Sigler as Nijinsky and Clara Superfine as Karsavina. © Donald Dietz. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/dd-jeux-34-shelby-finnie-anthony-sigler-clara-superfine-arch_1000.jpg)

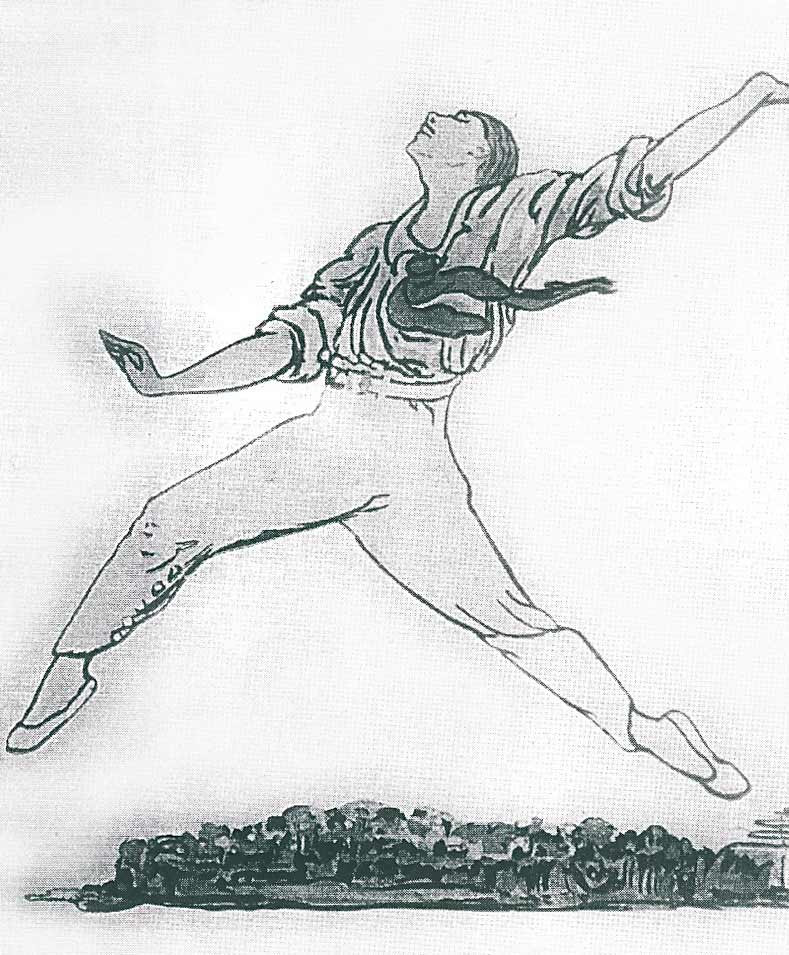

Anthony’s athleticism and ballet technique pleased us, but Millicent asked him to be a bit more British in his manner. Not an easy task: to imitate Nijinsky imitating an Edwardian Englishman. We noticed that, when Kenneth was on the floor photographing the dancers or talking to them about the costumes and decor, Anthony began to observe his scarcely Edwardian but nonetheless English body language. On our return in late March to complete the project, Susan Jaffe, still in her inaugural year as dean, had raised the already high technical standard of the students. Following the progress of Jeux, she teased us with the notion that Anthony was now “channelling Nijinsky”. Modest, affable, slightly introverted, Anthony resembled Nijinsky in the Jeux photos. In 1913 Debussy had observed that Nijinsky was always “adding up crotchets” and quipped that he was “a very mathematical gentleman.” (1) Anthony became meticulous about counts, and we could hear him, sotto voce, clocking the syncopations. They are especially marked in preparation for what we call the “Wimbledon leap” (a jeté croissé) when Nijinsky swept into a leap with his downstage leg closed to the audience (quite anti-classical), his arms in a tennis serve. Anthony studied the leap in a magazine drawing we had found from 1913. (2)

From the earliest rehearsals we wanted to see Shelby test her own limits. Formidable technique is a mother lode – there’s always more to discover. Her character in Jeux is sassy, quick-witted but vulnerable. She’s the first to be excluded in the tensions of the trio and the last to face the threat to their world. Shelby had the makings of her character from the outset, given to repartee, mood swings and droll humour. We hoped to tap these traits and use them to sharpen her technique in the specific style of Jeux. Shelby astonished us with her grasp of the role.

![Shelby Finnie as Ludmilla Schollar sulking when Nijinsky chooses to dance with the other woman at [28] of the reconstructed <I>Jeux</I>, UNCSA, 2013. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-28-shelby-finnie-sulking_1000.jpg)

During the spring rehearsals we pushed Clara – long and tall with very turned-out feet – to master the parallel stance basic to Jeux. She struggled with second position, the feet blocked and solidly planted. One day it emerged that she was a Barack Obama fan and loved basketball. That was the trick: we asked her to dribble, like she was actually defending on the court and, behold, a perfect parallel. The role of the Karsavina character has a touch of the Romantic and Clara was a natural. There is a moment when she must do a port de bras from Firebird, a Rimsky-Korsakov quote in Debussy’s score for which we adapted a gesture from Fokine. Her projection of Karsavina entrapped as the magical bird, a metaphor for her claustrophobia in the Jeux triangle, stunned us and her fellow students. At the technicals some of them came up to us and marvelled, “We never knew Clara could dance like that.”

![Anthony Sigler as Nijinsky grasps Clara Superfine as Karsavina when she tries to escape at [49] in the reconstructed <I>Jeux</I>, UNCSA, 2013, The <I>port de bras</I> is a quote from Karsavina’s duet with Fokine in his <I>Firebird</I> from 1910. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-49-firebird-quote-c_1000.jpg)

During our initial production meeting for Jeux Katharine Laidlaw had pondered the ballet’s “mature subject,” reminding us that some UNCSA students are still in high school, have curfews, need parental consent to leave the campus.. Were we overestimating what the dancers could do? Laidlaw assured us the students would rise to the occasion. They did not disappoint. Conversations with Mauceri, Jaffe, Laidlaw and the dancers grew richer and more complex as the project evolved, often through email as the two of us travelled to different countries rehearsing and lecturing on The Rite. We exchanged thoughts and references with Mauceri about Europe at the time of the first world war, with Jaffe about choreography, with Laidlaw about Nijinsky biographies, rehearsal photos with the dancers and all kinds of shop talk with the technical staff.

Mauceri located an early recording of Jeux by Pierre Monteux. the conductor for Nijinsky’s Paris premiere in 1913. So we were debating Jeux tempi ages before we got into the studio with him. He sent us many questions – from the fit of Nijinsky’s trousers to the timing of the infamous triple kiss at the end of the ballet when the trio lie down together on the ground. In 1913 the erotic ambiguities of the choreography had troubled Debussy. Mauceri, it seemed to us, wanted to conduct the piece from inside these ambiguities. We were thrilled to have a maestro probe the meaning of the ballet as we had done during the years of our research and reconstruction.

Jeux in Paris and London, 1912-1913

After its first night in Paris on 15 May 1913, Jeux had several more performances there before the Ballets Russes moved on to London, where the title was euphemistically translated as Playtime for its opening at the Drury Lane Theatre on 25 June. Two girls and a young man meet in a park after a tennis game. It is dusk. Electric lights cast cool shadows. Sounds innocent enough. But from the outset Nijinsky set up attractions that broke codes of Edwardian conduct, not just the man toying with his two companions, but the women making advances to each other and, ultimately, the three forming a ménage à trois.

Jeux goes down in the history books as the first ballet to address modern sexual mores and the first performed in modern dress. It was danced in clothes that had nothing to do with either ballet or tennis in 1913. At that time men wore cricket-style flannels for the game and women negotiated long full skirts. Instead, Nijinsky asked Bakst to imagine how tennis would be dressed in 1920. The designer produced for the girls chic A-line skirts cut to the knee with cropped jumpers and for the man shorts with braces. Diaghilev took one look at Nijinsky in the proposed costume and demanded that a version of his rehearsal gear be made – a silk shirt and close-cut jodhpurs, complementing the snug fit of the female garments. The Mariinsky ballerinas Karsavina and Schollar wore short socks with their pointe shoes, an oddity for the public, but the effect was fresh and athletic. It made sense with the blunted lines of Nijinsky’s choreography, which squared off the curves of classical dance and imitated cinema with its stop-and-start phrasing of movement. The sports-loving British cheered Nijinsky for making tennis the subject of a ballet – apparently another first. Had there ever been a ballet about sport? But Brits were perplexed that the actual game figured so little in Nijinsky’s creation. It was all about scoring points – but emotional ones.

Diaghilev had commissioned the music from Debussy right after the Paris scandal of Afternoon of a Faun in the spring of 1912. That summer, in London, Nijinsky worked with designer Leon Bakst on the new ballet. It was the winning Faun team together again; only now, writing a score to Nijinsky’s scenario, Debussy was dubious and kept remote from the process. He participated only through correspondence and conversations with Diaghilev and his go-between, Jacques-Emile Blanche, a painter, writer and unofficial agent of the Ballets Russes. (3)

Diaghilev wanted Nijinsky to make a ballet about a threesome of men. The choreographer’s transformation of the male love triangle idea into a mixed gender trio gave him more dramatic scope and no doubt less censorship. Liberties taken for granted in the 21st century were hard won. Homosexuality was illegal in England, and while lesbian relationships were less censured in France than England, they were not sanctioned by European society in that period. Still, critics on both sides of the Channel skipped over the sexual politics of the ballet, perhaps because the female roles seemed so youthful, naive, adolescent really.

The Disappearance of Jeux

Jeux, like The Rite, was performed in Paris and London from late May to late July 1913. That was it. Diaghilev never revived Jeux, not even with a different choreographer, as he did with Massine’s “second Sacre” in 1920. During the war years Nijinsky was out in the cold due to his marriage on the South American tour in autumn 1913, for which Diaghilev had fired him from the Ballets Russes. Just before the tour Nijinsky learned that Diaghilev was cutting Jeux and The Rite from the company roster; opera house directors did not want Nijinsky’s modernist anomalies and called for the return of Fokine. Maybe Nijinsky saw marriage with the Hungarian socialite Romola de Pulska as a way to preserve and pursue his choreographic revolution.

![Clara Superfine as Karsavina, briefly abandoned by the others in the trio, gazing into a flowerbed where she sees a bright vision of the future at [43] in the reconstructed Jeux, UNCSA, 2013. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-43-clara-superfine-bright_1000.jpg)

Yet when Nijinsky organized a season of his own in London in 1914, he only included Faun from among his creations. The season foundered. Diaghilev mocked him. In 1916, however, when the Ballets Russes was suspended due to hostilities in Europe, the Metropolitan Opera offered a North American tour on condition that Nijinsky lead it. Diaghilev agreed. Nijinsky had been in Budapest with his young wife when the war broke out. As an enemy alien he was put under house arrest. The Met tour set him free, but the repertoire was, by all accounts, determined by the Met and included neither Nijinsky’s Rite nor his Jeux.

Nevertheless, an intriguing interview during the tour records something of the choreographer’s thoughts on his work at this time. The critic H. T. Parker, writing in November 1916 for the Boston Evening Transcript, paraphrased the interview, no doubt infusing Nijinsky’s words with his own distinct voice. But the interview reveals the status of Jeux then:

In “Jeux” [Nijinsky] sought to simplify and spiritualize light fancy until the audience should forget that it was looking upon youth that might be on their way to or from tennis, yesterday, today, tomorrow and feel only the play of ever-renewed young moods, caprice, pastime and affections. (4)

This tepid description of Jeux accords with Diaghilev’s original publicity. Nothing of the ballet’s undercurrents are there, not even the anxious euphemisms of reportage in France and England about the “jeux d’amour” as well as “jeux de sport”. Nijinsky must have wondered if anything but Faun would ever be staged again.

![Clara Superfine as Karsavina gazes into another flowerbed where she sees a dark vision of the future at [43] in the reconstructed Jeux, UNCSA, 2013. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-43-clara-superfine-dark_1000.jpg)

After the tour of North America, urged by his wife, Nijinsky turned his back on a very real rapprochement with Diaghilev in Madrid in 1917. Suddenly the Nijinskys disappeared from public life in Switzerland where the dancer trained alone on the balcony of their villa in St. Moritz. He did masses of abstract drawings, made notes on dance theory and, fighting recurrent depression, created a farewell solo performance in January 1919. He then wrote his famous Diary, revealing, among much else, a state of deep denial about his choreography. The Rite remained unmentioned. And he simply dismissed Jeux as Diaghilev’s fantasy about a pair of male lovers. Nijinsky went with his wife to Zurich, thinking to meet publishers for his Diary. Instead he was put into the first of numerous mental institutions, where the Diary was used as proof of his madness. (5)

The Last Summer of Peace before the First World War

The year Nijinsky created The Rite and Jeux was stressful on many levels, not just the struggle to forge his “new dance”, as he called it, but the rest of life, too. During the company’s constant touring and performing across Europe plus his bouts of flu and tiffs with Diaghilev, Nijinsky brooded on Jeux. He had made a strong start in summer 2012 then abandoned it for a while, perhaps because his sister Bronislava, key to the cast, had become pregnant and was replaced by Schollar. It also seems he had arrived at a point in the scenario which blocked him: the ménage à trois. When he did return to the piece, finishing just before the premiere, we think his interpretation of his scenario had altered.

Nijinsky captured Edwardian Englishness to a fine degree in Jeux, recalling the luminous evening he and Bakst had seen the painter Duncan Grant playing tennis at Lady Ottoline Morrell’s in Bedford Square. “Ah, quel decor,” they famously sighed, as the young man darted about in his whites against the darkening greens of the garden. Lady Ottoline was the only London hostess and patron with whom Nijinsky could communicate in his limited French and virtually non-existent English. He visited her often. At the parties she gave for him and the Ballets Russes he met the Stephen sisters – the painter Vanessa Bell and the younger one who would, within in a year, get married, publish her first book and become known as the novelist Virginia Woolf.

Already there was a triangular attraction between the sisters and Duncan Grant. They all went to Ottoline’s parties to observe Nijinsky, but he beat them at their own game, catching how they moved, how they stood still, and how they watched each other. These Bloomsbury figures were, we believe, models for the trio in Jeux. Grant’s influence on the male role is widely accepted. But it was discussions with Nijinska’s daughter Irina (the baby who changed the cast of the ballet) which revealed the connection to Virginia Woolf and her sister. (6) In Jeux Nijinsky explored British restraint and Bloomsbury license, embedding this paradox in a taut structure of stripped-down classical steps.

![Millicent Hodson teaches the Cambodian phrase to the trio and the female cover, Kate Baier, at [51] in the reconstructed <I>Jeux</I>, UNCSA, 2013. Nijinsky saw Rodin’s drawings of Cambodian dancers at the artist’s studio and, we think, adapted such movements for the gamelan simulations in Debussy’s score. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-51-cambodian-phrase-c_1000.jpg)

During the final period of Jeux at UNCSA we had the unprecedented experience of working directly and consistently with the orchestra, even during recording sessions, remarkable for all concerned. The dancers and musicians communicated, unifying the performance of Jeux. On one occasion Maestro Mauceri stopped the music and said, “Here’s the most sensuous movement in the whole ballet – put down your instruments and have a look!” The student orchestra was enthralled. Questions poured forth from all our collaborators but from Mauceri in particular. “Surely Nijinsky saw these three Bloomsbury residents play tennis together,” Mauceri asserted. Maybe. In the summer of 1912, when Duncan Grant and Virginia Woolf shared a house in Brunswick Square, Vanessa Bell lived just a few blocks away in Gordon Square. They could well have met up for lawn tennis at either residence. But it is improbable that Nijinsky, busy with rehearsals, came round to see them play. He could have watched a game with all three, not just Grant, at Lady Ottoline’s, but that too is unlikely. She was possessive about her time with Nijinsky and wrote about each visit to friends who taunted her with jokes about her obsession with the dancer. (7)

![Kenneth Archer documents Millicent Hodson teaching the Cambodian phrase to the cast, including the male cover, Tommy Burnett, at [51] in the reconstructed <I>Jeux</I>, UNCSA, 2013. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-51-documenting-cambodian-phrase-archer-hodson-c_1000.jpg)

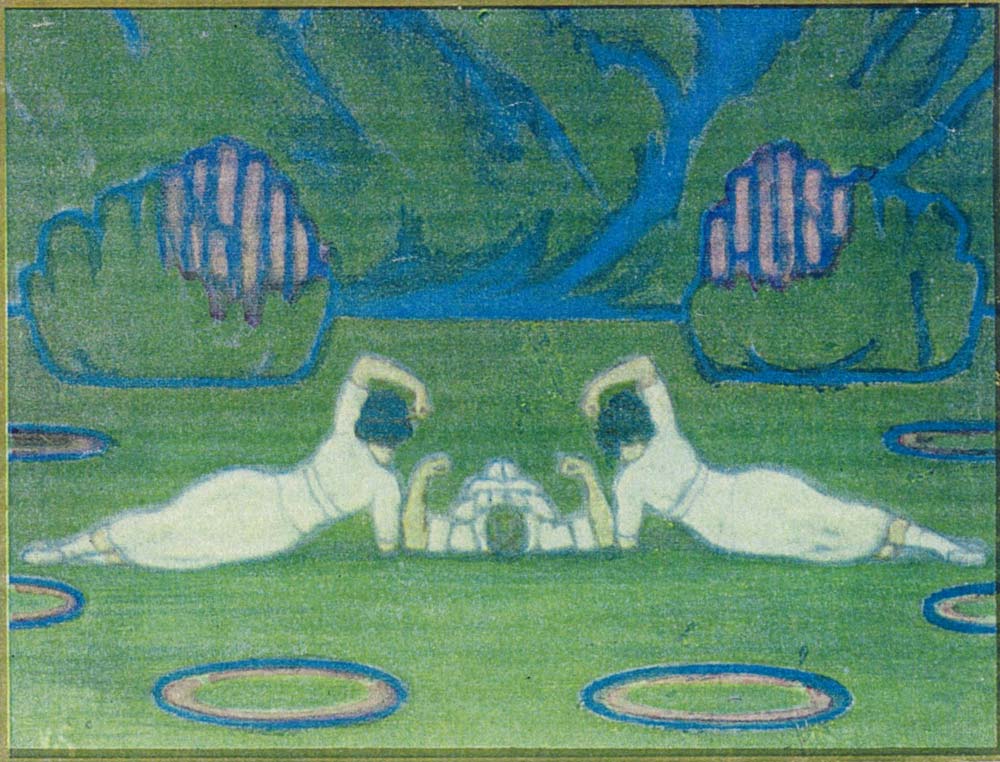

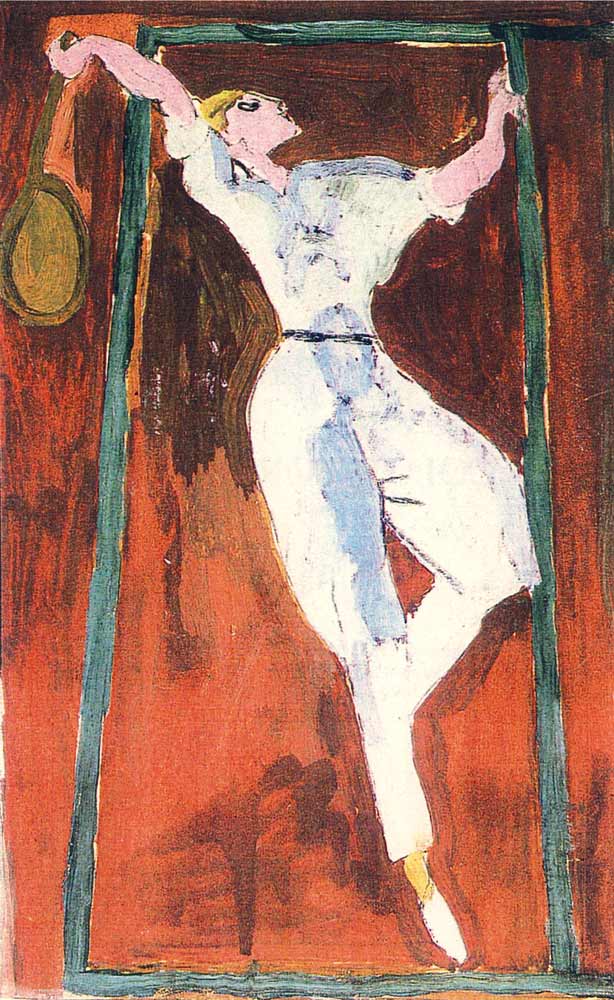

Another question from Maestro Mauceri and the dancers was whether the Bloomsbury models for the Jeux trio had ever seen the ballet, and thus Nijinsky’s portraits of them, on stage. Over our years of work on Jeux we have trawled through memoirs, collections of letters and biographies trying to place Grant, Bell and Woolf at the Drury Lane from late June through July 1913. To no avail. We can, however, track their involvement with each other. Duncan Grant was essentially homosexual but he and Vanessa Bell were beginning a close artistic liaison that soon became an actual affair. Meanwhile, Grant was considered by some Bloomsbury friends as a potential husband for Virginia, until she had become engaged in July 1912 to another lodger in the house at Brunswick Square, the writer Leonard Woolf. (8) During the summer of the premiere, Vanessa Bell was mostly out of London with her husband and children so probably missed Jeux. We think that Grant, however, did see the ballet. He painted a vibrant picture in 1913 of a tennis player with powerful Nijinsky thighs and the exact costume by Bakst. Of course, Grant could have seen black and white photographs of the Jeux in a magazine. But he very likely saw the ballet. Grant was as obsessed with Nijinsky as Lady Ottoline. For years he performed imitations of the dancer at parties and made drawings reminiscent of the Jeux dancers. (9)

Virginia Woolf had loved the Ballets Russes since it first came to London in 1911. That season she showed up at a fancy dress ball costumed as Cleopatra after Ida Rubinstein in the Diaghilev production (10). Virginia and her husband Leonard often went to see the Russian dancers perform. During the first week of July 1913, she was briefly in London and could have seen Jeux at Drury Lane. That month, however, she was already suffering another breakdown that led this time to attempted suicide. Despite the Bloomsbury habit of artists and writers using each other as subjects for their work, we doubt the sisters would have identified themselves on stage, even if they had seen the ballet. But Grant probably saw and recognize himself. Nijinsky’s identification of the trio with these Bloomsbury figures may have been unconscious, though the gestures of Vanessa and Virginia and the postures of Duncan seem unmistakable in photos and drawings that remain from Jeux. (11)

Nijinsky’s great achievement was to find gravitas in the seemingly frivolous encounter of this ballet which Diaghilev had originally announced as a “children’s flirtation in a park after a game of tennis”. (12) The action of Jeux builds slowly through intense couplings and triplings. A lot happens in the quarter of an hour or so that takes the trio from sunset to dawn, when their three-way tryst in the grass is interrupted by the crash of a tennis ball right beside them. Nijinsky called Jeux a “dance poem,” presenting images of moths in lamplight, snatches of social chat turned into gesture, fragments of the turkey trot and tango, poses from Gauguin and faces like the ones Modigliani painted, empty of expression but full of meaning. A critic for The Times in London declared pity for the dancers, wishing “to unbuckle their limbs for them and set them free” and proposing to cover their blank faces “with masks”. (13)

It was Nijinsky who disclosed the dark centre of foreboding in Jeux, deepening the significance of Bakst’s pleasure garden and Debussy’s rhapsodic, jazz-inflected score. In Bloomsbury during the gestation of Jeux Nijinsky had been exposed to all the “isms” of the era – French post-impressionism was in vogue, British socialism, feminism, and pacifism were burgeoning. In the reconstructed Jeux, when the music breaks into 2/4 time from its customary variations on the waltz, the trio march as though to their doom. After the so-called Great War, there was one man to every two women in Europe. Nijinsky seems to have turned foreboding into the climax of this ballet, picking up the premonitory hush in the leafy squares around the British Museum and the sexual and political tension he read in the body language around him. Bloomsburians, as the adage goes, “loved in triangles and lived in squares”. Nijinsky caught the meaning of their geometrical lives. When the waltz resumes, accelerating, the dancers in the reconstruction cut in on each other frantically. Will he go? Will he return? To me? To her? Will we all be together again? They embrace, holding on for dear life.

Shortly after that in the ballet, according to sketchy annotations Nijinsky made on a piano score, comes a definitive moment. He wrote the Russian word чрех (chrokh), meaning “sin.” It occurs at [73], just before the trio “behave like mad people,” then, as he said, they are “crazy,” and “enraptured.” Although the annotations give just rough ideas and occasional movement clues, they show the choreographer thinking. When we encountered the annotations – they became public almost a decade after we premiered the reconstruction in Verona – we wanted to figure out what the word “sin” meant to Nijinsky when he wrote it and how, as we sensed, the meaning of the word imploded at the end of Jeux. Our reconstructions are a kind of dance archaeology, building a facsimile of a ballet. The reconstructed Jeux was based on how it was reported in reviews and memoirs and reproduced in photographs and drawings of the time. The annotations, however, like Nijinsky’s Diary, tell us more about how he looked at his work. (14)

The passage Nijinsky marked “sin” occurs in the music as the trio turns away from its moonlight reverie to face reality. In his annotation, probably made early in the process, Nijinsky merely adds the instruction that the dancers are “en pointe” (he actually contemplated wearing blocked ballet shoes like the women but abandoned the idea). His assistant in that period, Marie Rambert, maintained that pointe in Jeux meant 3/4 pointe. (15) In the reconstruction the movement at [73] is the promenade of the three dancers in high relevé (3/4 pointe), walking stiffly in line as if carrying glass balls, “the crystal moment” of William Plomer’s poem about Jeux, “in the last world peace before the First World War.” (16) The Nijinsky character collides with Schollar in front of him and falls to the ground, letting go of the ball as though his life is crashing around him. The logic of the annotation is that all three react to some shock (in the reconstruction the collision and fall) with mad frenzy then rapture. Nijinsky wrote the note “sin” again at [78] when the trio embrace, interlacing their arms and pressing into each other, the grouping Diaghilev called “the fountain” and declared a masterpiece. (17) But now they intensify the movement by squeezing together. At this point, we think, sexual attraction has turned into mutual desperation.

![Clara Superfine, Anthony Sigler and Shelby Finnie as “the fountain” turns into a closer embrace and the three-way kiss at [78] in the reconstructed <I>Jeux</I>, UNCSA, 2013. © Kenneth Archer. (Click image for larger version)](https://dancetabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/ka-jeux-78-fountain-clara-superfine-anthony-sigler-shelby-finnie_1000.jpg)

From the hindsight of the Diary, Nijinsky, like Debussy, apparently disapproved of the triple kiss. Yet he managed a climax for Jeux that caused unease far more profound than what Debussy’s critics called the composer’s “prudery.” When the trio give in to the triple relationship, we can understand it as a sign of fear, hope for survival, a grasp for unity in the face of a common threat. That does not diminish the erotic promise of the ménage à trois, as the discrete pastel by Valentine Gross manages to suggest. Nijinsky’s “loss” of his sister (his muse and confidant, his double in a different gender) triggered, we believe, an alienation that kept him from working on Jeux for a while. We also believe he was conflicted about the triple kiss section. But, forced to finish the ballet for the premiere, he seemed to redefine his sense of loss and conflict into the larger threat of war. Bloomsbury foresaw the end of their pleasure garden, the erosion of their generation and the terrifying invention of aerial bombardment. That, we think, is the meaning of the tennis ball crashing on stage at the end of Jeux. (18)

The Aftermath of Jeux, 2013-2014

This interpretation of Jeux we have argued in lectures and publications during the various stagings of the reconstruction. (19) The change in Maestro Mauceri’s view of Jeux over the months we worked together fascinated us, as he was considering the implications for Debussy, too – what the score, intentionally or not, may have conveyed about the pre-war ethos in Europe. Mauceri shared his views with the dancers and musicians, as did we, and kept pursuing the idea of a film to document this production of Jeux. With Laidlaw he succeeded in engaging director Matthew Diamond, renowned for films of the performing arts and transmissions “Live from the Met”. UNCSA organized the shoot right after our last matinee of Jeux at Chapel Hill so that all involved in the production were on hand to consult as Diamond filmed. Mauceri also proposed doing an e-book to provide context for the Jeux film. In a letter asking us to contribute to it, he explained the change in his point of view to what he now regards as “the Debussy-Nijinsky ballet called – not without irony – “Games”:

This work is nothing less than a prediction of a future world, imagined through the magic of electric light. Somewhere in the process of setting this scenario, Nijinsky moved from a charming piece about three in a park at sunset, into a story of two desperate women and a young man as night falls – and that night is the Great War. When Debussy writes “violent” in the run-up to what was once the infamous triple kiss, it is no longer a triple kiss, but rather a pure physical representation of three humans, standing next to each other, linked only by their arms and then slowly melting into the earth – a very different climax! (20)

It remains to be seen whether musicologists and dance historians will seriously rethink this lesser-known masterpiece from Diaghilev’s 1913 season. Soon a professionally produced film of the reconstructed Jeux, with stellar performances by UNCSA artists, will be available for study. The depth of the collaboration on the ballet and film was gratifying for us. And it was especially poignant to witness the reaction of our youngest ever cast of dancers, and their classmates in the orchestra, to this reading of the ballet, echoing as it does the many “jeux de guerre” facing their generation.

–oOo–

References

(1) Letter from Debussy to Robert Godet, 9 June 1913, Francois Lesure, ed. and Roger Nichols, ed. and translator, Debussy Letters, Faber and Faber, London, 1987, p. 272,

(2) Pamela Colman Smith drawing, found loose at the back of a William Beaumont Morris Scrapbook, London Theatre Museum. For the story of the “lost” drawing, see transcript for Millicent Hodson’s Selma Jean Cohen Fulbright Lecture in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet: Jeux, Hillsdale, New York, 2008, p. 275.

(3) Documented in “Nijinsky’s Annotations and the Chronology of Jeux”, Hodson, Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, Jeux, pp 30-52.

(4) H. T. Parker, “Manifold Nijinsky,” included in Motion Arrested, The Dance Reviews of H. T. Parker, ed. Olive Holmes, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Conn., 1982, p. 108.

(5) For analysis see Joan Acocella, introduction to The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, Unexpurgated Edition, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1999 and Peter Ostwald, “Playing the Roles of a Madman,” A Leap into Madness. Robson Books, London, 1991, pp. 198-203, p. 201 in particular. For specific reference to Jeux, see Hodson, “Two Halves Do Not Make A Whole” in Nijinsky, Legend and Modernist, edited by Erik Naslund, Dans Museet, Stockholm, 2000, pp. 68-85.

(6) Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson, Interview with Irina Nijinska, New York, 1982, later discussed in “Three’s Company”, Part I, Dance International, Vol. XXIV, No. 2, Vancouver, Summer, 1996,pp. 4-9, reprinted in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, pp. 263-270, see p. 266.

(7) Miranda Seymour, Ottoline Morrell: Life on the Grand Scale, Hodder and Staunton, London, 1992, Sceptre edition, 1993, pp. 223-232. For more detail, see Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey A Biography, Penguin, London, 1971, 1979.

(8) See Lytton Strachey letter to Leonard Woolf, quoted in Victoria Glendinning, Leonard Woolf: A Life, Simon and Schuster, London, 2006, p. 115.

(9) Richard Shone, ed. The Art of Bloomsbury: Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, Tate Gallery, 1997, plate 102, p. 179.

(10) Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf, Vintage, London 1997, p. 239.

(11) Archer and Hodson, “Three’s Company” in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, p. 266.

(12) Quoted in Nesta MacDonald, Diaghilev Observed By Critics in England and the United States 1911-1929, Dance Books, London, 1975, pp. 93-94.

(13) The Times, London, 26 June 1913, quoted in MacDonald, p 93.

(14) For a discussion of the annotations and comparative critical views, see Hodson, Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, p. 31 .

(15) Millicent Hodson, Interview with Marie Rambert, London, April 1979. In Marie Rambert’s autobiography, Quicksilver, Macmillan, London, 1972, p. 69, she says “half-point” but indicated by gesture in the interview the full height of the relevé, concurring with testimony by Lydia Sokolova; see Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, p. 264.

(16) William Plomer’s poem about Jeux is quoted in Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson, souvenir programme Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, May 2000. Reprinted in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, p. 1.

(17) Quoted from Richard Buckle’s biography, Nijinsky, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1971, p. 287. For discussion of this grouping in its art historical context, see Millicent Hodson, “The Three Graces and Disgraces of Jeux” in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, Jeux, pp.9-24, especially p. 12..

(18) Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson, “Bakst’s Pleasure Garden,” Dance Now, Summer, 1996, pp. 19-23 and “Three’s Company”, Vol. 3, Fall, especially p. 9. Republished in Nijinsky’s Bloomsbury Ballet, Jeux, pp. 260-262 and p. 269, respectively.

(19) The war issue is discussed, for example, in “Jeux at the Clore”, lecture-demo at the Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, May 2000, filmed but not distributed by French cinematographer, Hervé Nisic. Copies are in the Royal Opera House Archives and the media archives of Kenneth Archer and Millicent Hodson.

(20) Letter by email from John Mauceri to Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer, 26 April 2013.

You must be logged in to post a comment.