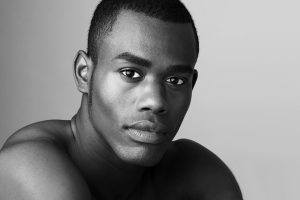

© Rachel Neville. (Click image for larger version)

Virginia Johnson: An American Ballerina

Wherever Virginia Johnson goes, she seems to travel on a cloud, with a kind of regal composure few possess in our day. She appears imperturbable. Sitting across from her at a café, her open, serene expression immediately puts one at ease, as does her voice, quiet and easygoing, but at the same time slightly formal, belying a steely sense of purpose. She describes herself as a “space cadet,” but this slight air of detachment that surrounds her has served her well, both as a pathbreaking black ballerina growing up during the Civil Rights movement and more recently as the Artistic Director of the renascent Dance Theatre of Harlem, forced to close for almost a decade because of economic troubles.

She is someone who gets things done. But it hasn’t been easy. When she graduated from the Academy of the Washington School of Ballet, in 1968, she was the only black student. Her teacher and mentor, Mary Day, advised her to look into opportunities in modern dance because it was unlikely – or, to be honest, practically impossible – that any ballet troupe would take her. Johnson’s hometown, Washington D.C., was being torn apart by race riots brought on, in part, by the assassination of Martin Luther King. It was a lot to think about, but she didn’t let it faze her. Johnson went to New York and, almost before she knew it, became a founding member of Arthur Mitchell’s exciting experiment, a ballet company based in Harlem. A place for black American ballet dancers to dance. She immediately became one of its top ballerinas – many would say, its prima ballerina – dancing roles as diverse as Sanguinic in Balanchine’s Agon, Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, Giselle, and the lead in Glen Tetley’s Voluntaries. (In addition to being determined, she was also versatile.) In 1986, Jennifer Dunning wrote, of her Blanche: “Johnson gives one of those flamelike performances that give the lie to her reputation as an almost exclusively lyric ballerina. All long, broken and stretching limbs, [she] is frighteningly intense.”

After a long career (twenty-eight years), she went back to college and, soon after, took on yet another experiment, a new ballet magazine, Pointe. She remained there, as editor-in-chief, until 2009. Then she got a call from Arthur Mitchell. The company was making a comeback. Would she be willing to try her hand at directing? She accepted the challenge, with some hesitation. It’s no secret that the world of American ballet has remained relatively closed to black dancers, especially women. Johnson is determined to change this, in part by changing attitudes toward ballet itself. A few weeks ago, we sat down for a long and winding conversation about her career, ballet’s place in culture, and her work at DTH.

© Matthew Murphy. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Tell me a little bit about your background and how you got started in ballet.

VJ: I’m from Washington DC. My mother had a very good friend, an extraordinary woman – she’s actually 95 and still teaching – who fell in love with ballet and wanted to be a dancer. Her name is Therrell Smith. She couldn’t find anybody to teach her ballet in Washington. Washington is still in many ways a segregated city, but back in the forties and fifties, it was completely that way. Two parallel societies. She was fortunate to be the daughter of a doctor and took herself off to Paris to study with Mathilde Kschessinska. And then she came back and opened her own studio. My mom wanted to support her friend, and sent her two daughters to study with her. She would drop us off on Saturday mornings and go off to do the grocery shopping and then pick us up. I fell in love with it right from the start. I was actually no good at it at all; I was uncoordinated and clumsy. I was three when I had my first lesson, and that clumsiness persisted until I was seven or eight. I was very shy; I think I was afraid to move. But I fell in love with it. I just loved dancing to the music. When I was thirteen, I auditioned for a scholarship with the Washington School of Ballet and Mary Day accepted me. [Mary Day was a distinguished figure in American ballet education and, for many years, artistic director of the Washington Ballet.] I got a scholarship to attend classes after four in the afternoon. When I went to high school, I got a scholarship to attend the academy. I graduated from the academy in April 1968 [at eighteen]. Dr. King had just been assassinated and the city was burning. There were riots all over the city, so to get to my graduation we had to cross the middle of the city, where all the tanks were. Mary Day was an ardent supporter of me as a dancer. But in the year I graduated she came to me and said, “well you know you’re not going to get a job as a ballet dancer, so you should really think about modern dance. I think you can dance, and you can have a career, but it’s not going to be in ballet.” That was the first time anybody had said to me that there was a reason I couldn’t do ballet.

MH: Had the idea never crossed your mind?

VJ: No, it hadn’t.

MH: Did your family support the idea of your becoming a dancer?

VJ: My mother taught school, everything from phys-ed to English, and my father was a physicist – he designed submarines for the Navy. They weren’t thinking I was going to be a dancer. They wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer or another kind of professional. Race plays a huge part of everybody’s story. As I said, Washington was a very segregated city, and even though my father worked for the Navy Department, he had a long history of battling with racism in institutions. So he wasn’t really thinking of me going into ballet, because he knew that ballet was a closed world. But they never thought I would go into ballet anyway, so there was never a discussion about it.

MH: Were you the only black student in your class?

VJ: I was the only one in the whole school. Mary Day had not welcomed African Americans into the school before. Mary Day was a tremendously complicated individual. A Washingtonian, she was a creature of her time, so her thinking was part of the territory. On the other hand, she could go against the social standards when she saw talent and I wasn’t the only beneficiary. In the sixties, she brought in Louis Johnson to choreograph for the Washington Ballet.

© Rachel Neville. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Did it feel like a crushing blow to be told you couldn’t have a career in ballet?

VJ: I just knew I had to dance. Ok, so there’s an obstacle; it’s like when you don’t know how to do a double pirouette. You have to learn. I wasn’t crushed, I was re-focused.

MH: What was it like to be a ballet student in DC with those huge events – the Civil Rights movement and the assassination of Dr. King – going on around you?

VJ: The rest of the world didn’t exist. It was only dancing. We weren’t an especially political family. We were told that we had to find a place for ourselves in this world. The world is not necessarily a friendly place, but you shouldn’t worry about that. You should find a way to make a place for yourself.

MH: And had you ever had a discussion about race at the school?

VJ: No, there was never a discussion. I was oblivious to anything that wasn’t dancing. There probably was all kinds of talk going on, I just wasn’t tuned into it. They just thought of me as that person over there who wants to dance.

MH: What did you do next?

VJ: To make my parents happy, I came to New York University as a dance major. I wanted to see if there was any way I could become a ballet dancer. I was there for a couple of months, down at the School of the Arts, before it was Tisch. Nanette Charisse taught class. It was a fantastic ballet class. But I really missed dancing fulltime. So somebody said to me, “Arthur Mitchell is teaching ballet classes on Saturdays up in Harlem, why don’t you go up there and get it over with and then come back and do some real dancing?” So I did. I found out that he was forming a company. And I had a very long discussion with my parents and convinced them that it was OK for me to take a leave of absence from NYU, where I had a full scholarship and a stipend, and go work in the basement of a church in Harlem with this guy Arthur Mitchell.

MH: Were they worried?

VJ: Of course. But they thought, “if it’s that important, how do you say no?” They gave me a year. And in that first year, things really took off. There was no looking back.

MH: Did Dance Theatre of Harlem feel like the thing you’d been looking for?

VJ: This was a place where I could dance. There was no other place. I wasn’t thinking racially, I was thinking: “I can keep going.” Certainly later on, dancers had the chance to think: “Do I want to keep trying to get into a white company, or do I want to just go over there and join a black company?” But there was no other choice at that point.

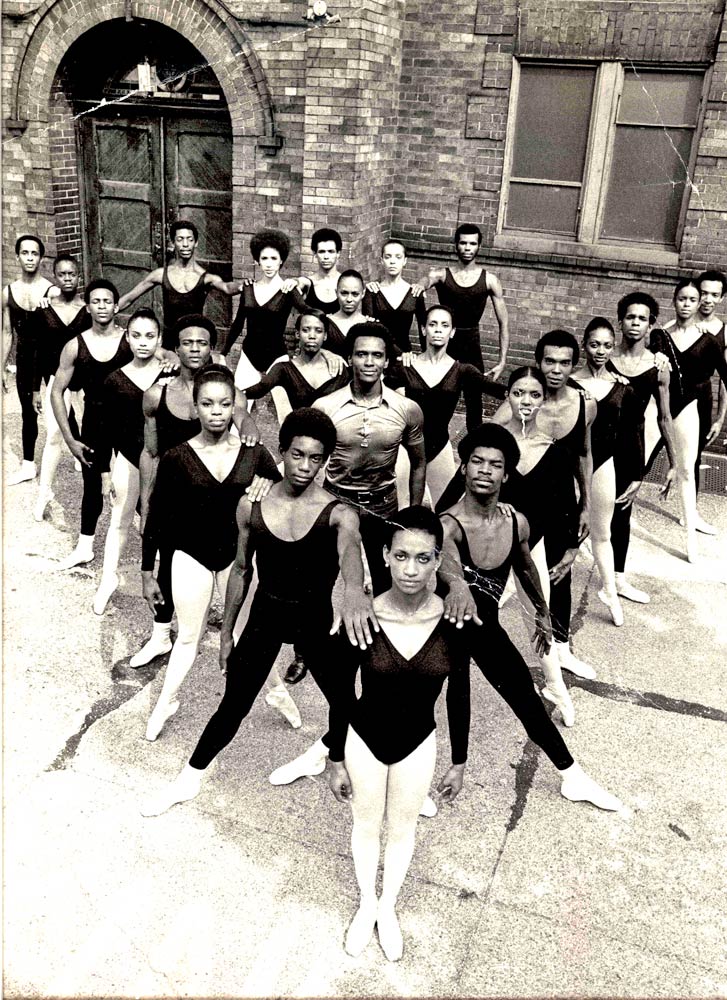

© Courtesy of the Dance Theatre of Harlem Archives

MH: What were those first years with DTH like?

VJ: It was a very exciting time. We were a group of people working for a “controlled maniac,” as Clive Barnes referred to Arthur Mitchell. A group of people who had been told, “you can’t do this,” being given a chance to do it. So there was a lot of commitment, a lot of “well then I’ll have to show you.” It was a fantastic environment. We came from all over the place, and there were many different styles of dancing. I studied with Mary Day; she was very Vaganova. The first thing Arthur Mitchell [whose background was with Balanchine’s New York City Ballet] said to me was, “you don’t know how to dance at all; I’m going to have to teach you everything.” It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, being torn down to nothing. But if this is what you want, this is what you want.

MH: What were your strengths as a dancer?

VJ: My strength was the very thing Arthur hated most: I was a very lyrical dancer. But my real strength was my persistence, my will to make this happen.

MH: Did you tour a lot from the beginning?

VJ: We started by doing what must have been hundreds of thousands of lecture-demonstrations, educational performances. Mr. Mitchell used them to turn us into a company. We didn’t do a full performance until fifteen months into our existence. The lecture demonstrations started with a barre, and then we would do some excerpts. We did a whole week of them out in Long Island with the Orchestra Da Camera. The first session was at eight o’clock in the morning. In your pointe shoes.

MH: What was Arthur Mitchell like?

VJ: Very dynamic, very very very demanding, very forbidding.

MH: What was your relationship with him like?

VJ: He was the man who was going to make it possible for me to do what I wanted to do.

MH: Were you close?

VJ: I don’t think he was close to any of the dancers. It was important for him to maintain that level of distance.

MH: Did that change over time?

VJ: It never really did. I would be his official date for some things. But it was like, “this is a business thing.” There’s much more individual conversation now.

MH: From the beginning, were you a star in the company?

VJ: I was one of the top dancers. And I think, looking back, that I was better than he ever let me think I was. That was one of his tactics. Lydia Abarca was the other principal dancer. There were probably twenty dancers by the time we started touring. I think we were never ranked, but there were people who did the principal roles. And there was Llanchie Stevenson, a wonderful dancer who had performed with the National Ballet in Washington. She was the real professional in the group. The rest of us were just kids.

MH: Were all the dancers black?

VJ: Occasionally we would have a white dancer, a Mexican dancer, an Asian dancer, it was always a mix.

MH: What was that transition like for you, from being a student to essentially being one of three principal dancers in a company?

VJ: I never felt like I was a principal dancer. I probably would have benefitted from having that feeling, but I never had it and it never came to me, because it was the doing that was important to me. When we got Allegro Brillante, I thought I was going to die; I didn’t think I could do it. I wanted to be the girl in the pink dress, but I didn’t think I could.

MH: Was Balanchine the hardest for you, technically?

VJ: Yes, I think so.

MH: What were some of your favorite roles?

VJ: Well I came to love Allegro, and Agon, and even Four Temperaments. But I liked the narrative works best. It was so much fun to dance Lizzie Borden [in Agnes de Mille’s Fall River Legend], but also to become Giselle. There’s something about telling a story with movement that resonated with me.

Virginia Johnson… as Lizzie, Blanche and others.

MH: Tell me about the creation of Creole Giselle.

VJ: Giselle was an extraordinary experience because it really brought together a lot of different elements. It was based on an actual historic community in Louisiana. When we were on tour there, a patron invited us over. He took a group of us into a study – Arthur Mitchell and me and a few others. He brought out these daguerreotypes and drawings of a community who lived outside of New Orleans. A whole culture of free people of color, who sent their kids off to Paris for their education, and who themselves owned slaves. It was a parallel society. That’s where I think the idea came from. DTH has always been about posing the question of who belongs in ballet. Giselle was not the first work from the classical canon that entered our repertoire. We had already done the second act of Swan Lake, Paquita, the Le Corsaire pas de deux. But the idea with Creole Giselle was to bring it new relevance. Carl Michel, the designer, did a lot of research as he put together the costumes and the designs. He worked with Frederic Franklin [who set the choreography] and Mr. Mitchell, conceptualizing how it would all make sense.

MH: Was that a very exciting time?

VJ: You know, Dance Theatre of Harlem was exciting from day one. It kept growing and growing, up and up. So you got to that place where you just expected more and more. It was all growth. I danced there for almost thirty years, because every time I thought, “it’s time for me to quit,” something new and exciting would happen.

MH: How did that marriage of setting and story fall into place?

VJ: You know, the story of Giselle is a basic human story. It’s about a cad, a young innocent, and the transformative power of love. It’s all right there. So it was a joy to be able to tell that story, to be inside of it. The [Adolphe] Adam music could be described as cheesy, but one can also use the words delightful and dancey and buoyant. The music doesn’t have a lot of weight, but when you put all the elements together, the ballet does have weight. When ballet is wonderful, it’s because the elements add up to something monumental.

Virginia Johnson in Creole Giselle

MH: What was your favorite moment in the ballet?

VJ: My favorite thing was the journey I had to go through during the intermission. That change from flesh and blood to spirit. You have to think differently. From the moment you’re lying on the floor, and you’ve died, and the curtain comes down, you start going into the second act.

MH: What was it like dancing the mad scene?

VJ: It’s that heartbreak, that feeling that the world has ended. It was very painful. I mean, have you ever been betrayed? It’s a physical thing. You can feel a knife in your heart, an actual physical knife in your heart. That’s the really weird thing about performance; you can do that every night.

MH: Are you more of an instinctual or intellectual dancer?

VJ: I think I was instinctual. I always felt dancing and experienced a lot of joy from it, but as I mentioned I was clumsy and uncoordinated from the beginning. To make up for that I had to tap into the intellectual to make up for my deficiencies.

MH: What was it like touring to the south?

VJ: We were part of the Civil Rights movement. We were founded [in 1969] at the cusp of the movement, and we became a manifestation of what was possible if given the opportunity. And we felt that. I can’t actually remember any overt dismissal of us as black people doing ballet, but that’s typical of me because I don’t think about things that don’t make me happy. Maybe things happened, but I don’t remember. We travelled all over the place, especially the South, and the thing that was wonderful about touring to the South was that we attracted huge African American audiences who had never seen anything like this and who were completely blown away by what it meant. We still attract a very mixed audience.

MH: Did you feel patronized?

VJ: I think people thought, “let’s go see if they’re any good.” And then by the end they were standing up and cheering.

MH: You were constantly outmeasuring their expectations.

VJ: Right. It was different from what they had anticipated.

MH: Did that put extra pressure on the company?

VJ: Of course. Arthur Mitchell was such a “controlled maniac” because he had certainly experienced racism. He was so difficult and tough with us that we didn’t have time to worry about what the audience was thinking. He was protecting us. Growing up black in America you have to be a credit to your people, and people think you can’t do anything. That was the world he grew up in. So before anybody else said we couldn’t do it, he would. He had to be tougher than anybody. And he could be brutal, but most of the time I was able to understand that the brutality had a purpose and that it worked. I can work for anybody in the universe now because I’ve worked with Arthur Mitchell.

MH: Did you talk about race in the company?

VJ: We talked about our passés and the roles we were dancing. There were probably some discussions. Arthur Mitchell would say, “when you go to the airport, you’d better look like you’re traveling in first class, because they’re going to be expecting you to come to the airport with fried chicken in your pocket.”

MH: How central was the school to the company’s life and identity?

VJ: Arthur Mitchell started a ballet company in Brazil, back in the mid sixties. He was on his way to the airport when he heard about Dr. King. And he thought: “why am I going to Brazil? I’m can use my expertise at home.” He really wanted to start a school. And he did. He ran the ballet program at Dorothy Maynor’s Harlem School of the Arts. Then he got foundation money, and one of the stipulations was that we had to have earned income. So he had to have a company. So the company was a second idea behind the school. He wanted to give children in the community a way to change their lives. It was about connecting to the community in a very specific way. But once DTH started, we were always on the road; so the school and the company were like two different things. By the time we got into the eighties, the school had established itself as this mega-monster, producing some dancers but mainly giving a huge number of young people the chance to go into the world and do something, to go off to college and become physicists or whatever. From the mid-seventies through the time I left at the end of the nineties, maybe a quarter to a third of the dancers in the company came from the school. There were always people whenever we performed in this or that city who wanted to audition. And people came from around the world to audition. We were like a magnet.

© Judy Tyrus. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Did you teach when you were dancing?

VJ: I taught a little bit. I’m not that big on teaching. Even now.

MH: You had such a long performing career [1969-1997]. To what do you ascribe that longevity?

VJ: Being a space cadet? [laughing] Having that singular focus. This was the thing I wanted to do; this was the thing I felt I was growing in and that I could keep growing in. And good fortune. I didn’t really have any injuries until I was forty-two. I didn’t have an easy body, I was never very flexible. I was just lucky.

MH: Did you ever dance Swan Lake?

VJ: Freddie Franklin set a version of the second act for us. I think that ultimately it was a disappointment to me because the music is so exquisite, and I knew I wasn’t getting anywhere near it. I wasn’t able to turn my body into the music. I didn’t have that endless continuity. I couldn’t transcend the technique.

MH: What was it like working with Freddie?

VJ: He was artistic advisor for a number of years. When we started to bring in the narrative ballets, in the eighties, Mr. Mitchell called up and asked him to come work with his dancers. But even before that, he brought Danilova in to set Paquita on us. She was incredibly sweet, which was not what we were expecting. And incredibly funny. She would come in, and she would be wearing all green, shoes and everything, and something in her hair, and she would stand there and put out one leg. She just had this style. And she was very soft-spoken. She would zero in on that moment when the knee is not quite at the right angle; the technical detail was there. But both what Freddie and Danilova both focused on was the flair of the movement, the shape of the movement, the sound of the movement. They really wanted us to communicate; they didn’t want us to worry about the technique.

MH: Is there anyone like that now?

VJ: Who has time, now, to do that? People used to be molded and nurtured. Now you have to have it, and you hold onto it for a couple of seconds, and then it’s on to the next thing.

MH: What did you do when you stopped dancing?

VJ: I decided I was going to have a real life. I finally went back to school. I went to Fordham full time to study communications, because I wanted to go into journalism. That was pretty fun. It was weird being forty years old in a class of eighteen-year-olds. It was a fun thing to see this other world. A couple of months in, I got an opportunity to interview for a job at Lifestyle Ventures, the publisher of Dance Spirit and other magazines. They said, “we’re thinking of starting a ballet magazine; why don’t you go home and write down some things that you think should be in a ballet magazine?” I made a big outline of all the things I wished someone had told me when I was a young dancer. And they said: “That’s really good. We want you to be the editor.” Can you imagine? So I became the editor of Pointe. I was there for ten years. The office was across the street from where I lived, so I would be there eighteen hours a day, learning all the bits and pieces. It was kind of like being a dancer. Our first issue came out in Feb. 2000.

MH: Did it already feel like dance journalism was on the rails?

VJ: Yes. It’s a very challenged field. And it’s so heartbreaking because so many people want to be part of it and have something to say. And people want to read about it. That was the big lesson for me about Pointe: it’s a business. A lot of the decisions that are made at these publications are business choices, not about the art form. It’s certainly been exacerbated by the Internet, which gets in the way but also gives us more opportunities. You couldn’t make a living then and you probably can’t make a living now. The same thing is happening with so many dancers. If you are fortunate enough to be in one of the big companies life can be good, but the vast majority of young dance artists have to cobble together a living with several jobs. I don’t know how to monetize the field. But I think that people want to think and talk about ballet in a meaningful way. Money is a pernicious thing; it doesn’t have a heart, or morals, or feelings. So if we’re going to change the situation, it has to be because people perceive a need for it. And the need for reading about dance has to be connected to the need to experience dance.

MH: Why do you think DTH came to an end when it did, in 2004?

VJ: You know that ballet William Forsythe did, Impressing the Czar, and how it reflects ballet’s origins in the court? Then Diaghilev came along and created a ballet company, but it ended up being a miserable financial failure. Because that czar mentality was still there: “We’re making beauty, and it has to be paid for, therefore somebody will pay for it.” Balanchine was fortunate to have Lincoln Kirstein, who had his feet firmly planted on the ground. But all of Balanchine’s acolytes – and Arthur Mitchell was one of them – felt the same way, “I’m making beauty, you have to pay for it.” We came to that crossroads earlier than most. You have to run this like a business: money in, money out. By 2004, we’d accumulated two million dollars in debt and people were saying, “we’re not going to just keep giving you money.” To save the organization, it was necessary to close the company. Mr. M didn’t think it was his job to make good business decisions; it was his job to make good artistic decisions.

MH: How did they get you to come on board?

VJ: So, they let me go from Pointe. Things had not been going well for me for a while there. I picked up my telephone one day, and it was Arthur Mitchell: “well you know I’m thinking about moving on. And I want you to take over.” And I couldn’t say no. How could I say no? It’s not something I wanted to do in a million light years, but if he’s going to ask me to do this, I have to at least give it a try.

MH: Is Arthur Mitchell involved with DTH today?

VJ: I talk to him frequently. He’s “emeritus.” I think he wanted to step all the way back in order not confuse people about whom to pay attention to. But we’re reeling him in. I think it’s just a matter of time.

© Rachel Neville. (Click image for larger version)

MH: What was the trajectory from the moment you agreed to come back to DTH to your first season?

VJ: My start date was January 1st 2010. I spent the previous summer putting together a five-year-plan with Laveen Naidu and the board. We had the company coming back in year three. In January 2012 we started auditioning for the company, in Chicago and San Francisco and Miami and here in NY, looking for dancers. And you know, I didn’t find people out there. It’s the same story as before: where are the dancers of color? Dancers are not in an environment where they’re expecting to find a job where they’re welcome. So people came to the audition who were just not ready, just not at the right level. With the exception of New York, in every one of those auditions, if there were fifty people in the room, there were just ten black people.

MH: Were you open to people of any background?

VJ: Yes, but we wanted this nucleus. It was very sobering. The disparity hasn’t changed. But you know, I think in the next five years there is going to be a big change. The problem of course is in the schools and this idea of what it is to be a ballet dancer. For many people, it’s so very narrow. It’s cruel, because first of all you have to conform to all these physical things. And for many people, even if the physical things are there, this one physical factor – skin color – makes it hard to see the others. We have a summer session going on right now and it’s one of the most joyous and heartbreaking things to me to get kids from around the country; for so many of them this is the first time that they’re in a classroom that really welcomes them. But I look at these dancers and I see that they’re not being corrected. There are some very basic things going on that reveal that they’re being ignored. And we see changes in them so quickly because they are finally getting corrections. The schools need to not only embrace the fact that ballet doesn’t have a color but actually work with the material in the room.

MH: Do you think teachers give up on black dancers?

VJ: No, I think they don’t even notice them. They’re not the material.

MH: It’s as if they had bad turnout.

VJ: Yes, it’s as if they had bad turnout. Or maybe their turnout needs working on and if they worked on it they would get it, but if it’s not already there and little Susy J has it all, they think, “I’m going to work with little Susy J.”

MH: Do you think that the visibility of dancers like Misty Copeland [of American Ballet Theatre] is important?

VJ: Absolutely. We do these things called “lemonades on the terrace,” and we had Misty come up last year to talk to the dancers. It’s very important, that notion of a role model.

MH: Is it the same for male dancers?

VJ: No, I think, in part because of the model of Arthur Mitchell, that many companies have at least one male dancer of color. It’s a normal thing. But the ballerina is a difficult position. For many reasons. To be a ballerina is to be an exception.

MH: Is it better than when you were dancing?

VJ: Yes, of course it’s better. It’s changing. Like an iceberg, but it’s changing.

MH: What does it mean today to be a predominantly African-American ballet company?

VJ: We’re a diverse company. We’re about changing people’s perception of what this art form is. People have to understand that ballet is not just Les Sylphides. It needs to speak to many different people in many different ways. So what we’re really doing is changing perception, because I think the art form is magnificent and important.

MH: Important in what way?

VJ: It’s about the human spirit and expressing it in its highest form. And I think that everything in popular culture goes in the opposite direction. Everything is about being casual and easy and down. There’s nothing wrong with that but there’s another side to being a human being.

MH: How do you conceive the repertory?

VJ: It’s really important to try to find a balance. To have a little of this, and a little of this, and a little of that, and something else that’s unexpected. I’m still a beginner at this. I just realized we only have two closers. So whatever performance we do, we have to end with either this ballet or that ballet. And I have to think about what’s going to speak to an audience.

MH: What works resonated on tour?

VJ: It really depends on where you are. I learned a lot watching the audiences in this first year. What I realized is that the mix is important because we don’t have a homogenous audience. Take Far But Close [by John Alleyne]: in some communities, people were living on the stage with the dancers. Laughing, sighing, crying. There was a whole identification with that narrative. Many people thought, “I’m not going to understand what’s going on,” but here we’re telling you the story. But in other places, some people thought it was too long, and they really loved The Lark Ascending [by Alvin Ailey]. A ballet that seemed to be a hit with everyone, though, was Robert Garland’s Return, set to the music of Aretha Franklin and James Brown.

© Matthew Murphy. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Does Balanchine still resonate?

VJ: It does. People really get that athleticism, they get that clarity and rigor. The funniest thing happened, though. In Detroit, someone came up to me and said, “I can’t take that music, that Stravinsky.” It was Agon. “That doesn’t sound like music. I like the dancing, though.” Can you believe that?

MH: What did you learn from the New York season?

VJ: It was pretty amazing to me how much people wanted DTH back. There was a lot of love. I think there were a lot of people who thought, “this is not what I was expecting, this is not enough.” I can accept that. That’s part of how you build something. We were nine months old when that curtain went up. And of course, we’re going to keep growing. I feel good about where we started. We’re turning ourselves inside out to have live music next year. But the Rose Theatre is expensive, so there were things we had to make choices about.

MH: What is your aspiration for your dancers?

VJ: I tell them all the time, “you have to be a company of soloists.” They all have to be brilliant and expressive and pristinely elegant. There’s a way of not being a body but being a musical note, a shaft of light.

MH: Are they very committed to being in this company of color?

VJ: Yes. Though I have to say, Michaela DePrince has left us. She got a contract with the Dutch National Ballet. She really did want to be in a white company. That was important to her. But our dancers know what we’re about. We’re about the art form and moving it forward. We’re not a social justice organization. It’s not just about being black, it’s about the art form of ballet. It’s not just a job; it’s not just a company, it’s a mission.

[…] This summer, I spoke with Virginia Johnson, the longtime star of Dance Theatre of Harlem, who is now the troupe’s Artistic Director. You can see the interview, on DanceTabs, here. […]

wonderful Wonderful WONDERFUL! I loved Ms. Johnson back in the day, she was my favorite. So happy to see the school & company back with her at the helm!

[…] For the complete Virginia Johnson interview click on this link: https://dancetabs.com/2013/09/virginia-johnson-artistic-director-dance-theatre-of-harlem/ […]

Another super interview. You have such a deft hand at extracting the story from the subject. You really brought Ms. Johnson to life and put her in perspective. Another great piece of work.

Correction: It’s Nenette Charisse, not Nanette Charisse. My apologies!

Great interview. I had the pleasure of being at the Washington School of Ballet and graduating with her. She didn’t have the best body, but when she danced…you could hear breathing stop…she’s that lyrical…..

she was also an amazing intellect and great person. Yes, it was a time of great change and I came from the South..Being at WSB helped cement my world view that people are people of all possible talents, not defined by ethnic race or other barriers. Virginia is also right, we were there becuase dance moved us…everything else was secondary.

Congratulations to Virginia…she’s still amazing!

Ballet is unfortunately exclusionary, not just for dancers but audiences as well. Putting the comments about the difficulties for black dancers into perspective, many of these issues don’t apply in Cuba where there is a state run ballet culture. Cuba is not without is potholes in the area of race but they have succeeded there with ballet in ways that we cannot hope to. It is not always about what you dance but sometimes where you dance. I had the same response to comments made by Eric Underwood, a black dancer who blogs on his experiences dancing with the Royal Ballet. Here is one of his blogs. http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2013/sep/09/ballet-problem-nonwhite-eric-underwood

I agree, though at the same time, I think all elite activities are exclusionary. I’m not sure if you mean the cost of the training and the tickets? In that case, yes, absolutely, the lack of state funding and education in the arts are a huge—perhaps the central—problem.

On a dark, crisp autumn evening in little Norway my gratitude, admiration and love are hereby carried from me (a little former dancer with the late ballerina Gerd Kjølaas (founder of New Norwegian Ballet)) across land and stormy seas to honor a true hero on many levels – Virginia Johnson! She has made the world richer, lifting it on keys of purpose, inner strength, dedication, beauty and the love of dance…

Aasve, this may be my favorite comment ever.

I do not understand how or why the comment about my daughter, Michaela DePrince, appeared in this article, or why her reason for leaving the Dance Theatre of Harlem was presented as her wanting to dance in a “white company.” The truth is that Michaela’s dream has always been to dance in a top tier world-class ballet company; one that is capable of producing the romantic classics and the neoclassical ballets with all of their delicacy, pomp and elaborate settings and costumes. She has said this many times in interviews. The fact that these companies are all white concerns her. Michaela does not agree with “Separate but equal: not in education, nor the arts. She believes that, like public schools, universities and industry, ballet companies should be integrated. She is working hard toward that end.

Dear Ms. DePrince,

First of all, thank you so much for writing. You bring up a lot of interesting questions. I think Ms. Johnsons’ reasons for mentioning Ms. DePrince (quite spontaneously, I might add) are rooted in her excellent dancing, which was such a feature of DTH’s season. [See my review here https://dancetabs.com/2013/04/dance-theatre-of-harlem-april-2013-revival-bill-new-york/, in which I wrote that “the prodigiously talented (and young) Michaela DePrince, would grace any ballet company in the country.”]

Ms. DePrince’s leaving the company—for Het National Ballet JC, I believe?— brings into relief some tough and unavoidable questions about the nature of DTH: What function does it play within the national and international ballet culture? Can the company keep the very best dancers it recruits into its ranks? How do the dancers perceive being part of a company like DTH? Is it a stepping stone to bigger and better opportunities? The answers are equally complex. I thought it was interesting when Ms. Johnson said: “we’re not a social justice organization.” But social issues are not far from the surface.

Every insight we can get into the knotty issue of diversity in ballet is invaluable. If your daughter would like to continue the discussion, I would be happy to.

All the best,

Marina

Another of Marina’s exceptional interviews. I had the pleasure of speaking

with Virginia Johnson at two International Ballet Competitions in Jackson,

and felt it to be such a privilege. I also felt she gave Pointe Magazine a special sheen which hasn’t been equaled subsequently.

I am particularly delighted to have seen the video clips of her dancing, for

I remember when DTH danced Creole Giselle at the San Francisco Opera

House, sponsored by San Francisco Ballet in the days when Michael Smuin shared artistic direction with Lew Christensen.

A friend a Agnes de Mille mentioned to me how impressed de Mille was

with Johnson’s performance in Fall River Legend. The clip helps to convey her

response to Johnson’s artistry.

Thank you, thank you for such absorbing reading.

Watching Virginia dance was pure pleasure; writing for her at Pointe Magazine was the same–her grace as an editor was the same as her grace on stage; dining with her one rainy Sunday night in Copenhagen was memorable. I thank the author for an enlightening and insightful interview, and I have one small correction: Virginia danced the Sanguinic variation in Four Temperaments, not Agon.

Dear Martha, thank you so much for your note and your stories. And of course, you are correct. Yet another “typo”–I was thinking of course of the The Four Temperaments.

M

Although I know Virginia was speaking from the point of view of how her performances of Swan Lake felt to her, I will respectfully disagree with her perception of not getting anywhere near the exquisite quality of the music, not turning her body into the music, or transcending the technique. She has simply failed to realize that she achieved exactly that, and more, for those of us who experienced her performances from outside her body. I viewed her Swan from both the front of house and backstage. In particular, as viewed from the wings, where every facial tic, bead of sweat, and strain in the attempt to approximate the illusion of physical perfection, is plain for the eye to see, Virginia was indeed as exquisite, frightened, in love, and ultimately as heart broken as the music. I am certain her many fans around the world were so moved as they lived the Swan’s journey through her utterly real emotional portrayal.

[…] posting my interview with the great American ballerina Virginia Johnson (now artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem) on DanceTAbs, I heard from the young dancer […]