© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Spectral Evidence, Soirée Musicale, Namouna

New York, David H. Koch Theater

8 October 2013

www.nycballet.com

Namouna Returns

Some ballets improve with age, or, to be more accurate, our eye evolves and we learn to see them better. I remember being befudled at the New York City Ballet première of Alexei Ratmansky’s Namouna, A Grand Divertissement in 2010. By the second viewing, I had started to warm to its oddball charm. And by the end of that season, I was smitten. Tonight, revisting this ballet for the first time in three years, it was clear that it is the best new work the company has commissioned since, well, Ratmansky’s Concerto DSCH (2008). What at first seemed puzzling – the deconstructed plot, the peculiar costumes – now only adds to its charm. It’s such a clever ballet, a little bit ironic, quite sophisticated, but in the end also tremendously warm and steeped in joy.

In its first life, Namouna was a late nineteenth-century adventure-story by Édouard Lalo and Lucien Petipa. Created for the Paris Opéra in 1882 (and inspired by a poem by De Musset), it was set on the island of Corfu and told the very slight, exotique story of a slave girl gambled away by an Italian Count. Ratmansky’s ballet does away with the game of dice, the harem, the exotic locale and most of the plot, retaining only a whiff of the ballet’s original atmosphere. His Namouna is a suite of dances and set-pieces, loosely strung together to suggest a love-quest. He has allowed Lalo’s marvelously descriptive score to be his guide. The overture, with its shimmering, ever-accumulating waves of sound, invites us on an enchanted voyage. Each dance is colored by Lalo’s evocative rhythms and witty orchestration (castanets, cymbals, tambourine); the shifting soundscape is as vivid as a series of scenery changes. Ratmansky brings these colors to life. Lalo would surely be pleased.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

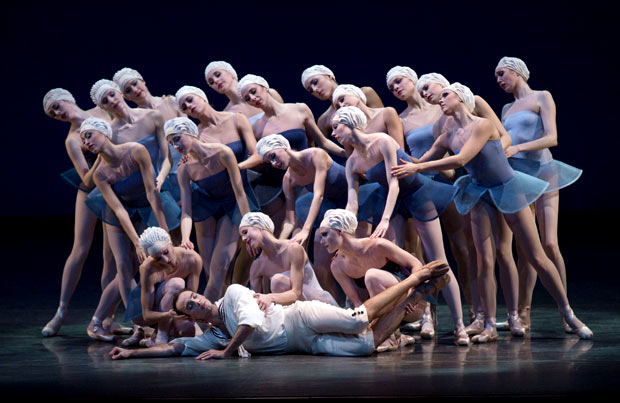

The ballet’s nautical atmosphere is further suggested by Rustam Khamdamov and Marc Happel’s costumes: the principal male character wears a sailor suit and many of dancers are in shades of blue (some even wear bathing caps). We are introduced to a young man – danced tonight by Tyler Angle – and three temptresses, possibly figments of his imagination (Ashley Bouder, Sara Mearns, and Sterling Hyltin). There is also a high-flying sidekick (Daniel Ulbricht), backed by two mischievous soubrettes (Abi Stafford and Megan Fairchild), whose skittering petit-allegro steps further add to the ballet’s varied texture. And, best of all, there is a chorus of nymphs in yellow sun-dresses and Louise-Brooks bobs, who tease and tantalize our young hero. (Touchingly, one of them falls in love with him and has to be held back by the others.) With this skeleton cast of characters, Ratmansky populates a fairy-tale world.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

As the ballet begins, the nymphs glide on, arms held out at their sides like the wings of art-deco birds. A sinuous line of them curves around the stage, then forms a circle, then a circle within the circle, blossoming outward like a flower. The inner core of women pushes the outer layer to the ground, suggesting a kind of agression. But then the victims of this agression arch their backs and pose like 1930’s pinups. Moments later, the nymphs form lines that advance like waves, arms slowly rising and falling. It is a ravishing beginning. A series of set-pieces follows. Sara Mearns, reprising a role she created three years ago, is a devastating femme fatale dancing a habanara overflowing with exuberant leaps and swoons. She dances with an army of men, flinging herself from one group to the next with a kind of voluptuous vitality. Her attendants fall to their knees in adoration; some are so overcome that they faint at her feet and need to be helped into the wings. Other than the twin role of Odette and Odile in Swan Lake, for which she is justly admired, this may be the ballet that most fully expresses Mearns’s almost terrifying forcefulness. At the same time, the character’s over-the-top exuberance is a joke, a riff on a certain type of irrepressible ballet heroine (think: Kitri). Ratmansky has given Mearns the chance to play a tongue-in-cheek version of her own onstage persona.

Then there is the alluring “cigarette” solo, originally made for Jenifer Ringer, a dancer who oozes old-fashioned glamor. (It was danced here by Ashley Bouder). She puffs away on her cigarette while undulating her free hand, mimicking the trail of smoke. She shakes one leg, hops on pointe, skitters like a cat on a hot tin roof, then peers over at our unsuspecting hero to calibrate the effect of her charms. (Bouder sharpens the edges of her characterization. She’s less beguiling, more devious.) When her antics fail to elicit the desired response, she plays dead, dangling limply in the arms of one of her attendants. Then she dusts herself off and smokes some more. Three girls repeat the sequence: puff, hand-wave, leg shake, hop. Then the larger ensemble joins in. The sequence becomes funnier each time, but also more abstract; it begins to look more and more like a dance, with its own beguiling rhythm and logic.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

There are many more felicitous touches in Namouna – more than I can mention here. But while we’re at it, here are just two more: a dream ballet in which the nymphs stretch and loll about, bowing their heads with late-afternoon weariness, and, a favorite, a lullaby in which the full ensemble rocks the hero to sleep, suspending him just above the floor. The final pas de deux is playful and tender; the two lovers (Angle and Sterling Hyltin, in the role created for Wendy Whelan) dance side by side and for each other with kid-like glee, as well as in each other’s arms. In an expression of his joy, the hero flings his bride into the air, catches her and lowers her, with a whoosh, into a swan dive. The scene is as triumphantly joyful as the finale of Sleeping Beauty. But what is even more thrilling is the over-abundance of ideas Ratmansky has poured into this hour-long ballet; it is a cornucopia of steps, with complex beats of the legs and quickfire changes of direction and constantly shifting coordinations of the torso, the shoulders, the head. It’s ballet made fresh again. In his hands, the dancers look articulate, complicated, sensual, witty. The costumes – long shifts or rigid flower-petal-like tutus, wigs, even, in some cases, close-fitting caps – are fanciful and strange to be sure, but they work within the dream-logic of the piece. Little flickers of mime (“I remember,” or “what’s that sound I hear in the distance?”) form a bridge to the ballet’s nineteenth-century origins. Ratmansky is hyper-aware of ballet’s clichés, and he embraces them, with a twinkle in his eye. “Yes,” he says, “it’s all right to love these ballet clichés. I love them too.”

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

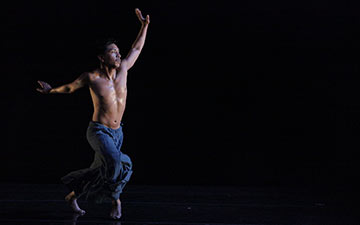

The program was rounded out by a performance of Angelin Peljocaj’s Spectral Evidence, new this season, and a pice of Wheeldon juvenalia, Soirée Musicale. The latter is a light, pouffy piece from 1998 inspired in part by Balanchine’s La Valse but also by Hollywood notions of ballet style. (It was originally created for the School of American Ballet’s end-of-year performance.) On this evening, the fresh-faced cast, containing several débuts, was still slightly rough around the edges, but then again, the ballet suits young dancers. The men are in well-tailored suits, the women in flattering, gauzy skirts that skim the calf. This suite of balleticized social dances – a scottische, a waltz, a tango, etc. – is sweet and pretty enough, but evaporates as soon as the curtain closes. [I reviewed it in depth earlier] Spectral Evidence, on the other hand, tries all too hard to impress with its air of mystery. [My original review] Accompanied by a series of John Cage vocal pieces (and an interlude of electronic music) four waifs in white shifts entice and then fall prey to four men in priestly garb. (Preljocaj has said that the ballet was loosely inspired by the Salem witch trials.) At first, the women handle the men like puppets; then they perform a kind of witchy circle-dance, set to Cage’s sighs. Two of the characters, danced by Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild, share a tender moment – they tussle and kiss. (The duet’s romantic feel clashes with the rest of the ballet.) Afterward, Fairchild performs a kind of self-exorcism, lip-syncing, to somewhat comical effect, along with the sound of John Cage’s moaning and whimpering voice. The waifs are burned alive in white boxes that, once laid flat, become their tombs. Earlier, the white boxes had been configured as a kind of altar. Both the costumes, by Olivier Thuyskens, and the uncredited stage design are intriguing.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

But despite some striking moments, Spectral Evidence becomes increasingly bogged down by its conceit. The formulaic structure doesn’t help. Groups – all women, all men – dance in unison while others watch, standing behind a wall of white boxes (or disappearing below them). There is no counterpoint, no play with entrances and exits. Performed alongside a ballet as imaginative and many-layered as Namouna, Preljocaj’s invention looks all the more flimsy. One feels as Débussy did when he wrote, at the end of the nineteenth century, that “amid too many silly ballets, Lalo’s Namouna is something of a masterpiece.”

[…] review it here, for DanceTabs. And here is a short excerpt: “Some ballets improve with age, or, to be more […]

What an enchanting review. For someone who sadly will not be able to attend (but would have loved to), you brought this performance to vivid life. Thanks so, SO very much, Ms. Harss. Bless you for this.

[…] You can read more about it here. […]

[…] You can read more about it here. […]