© 2013 Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

Sentimental Education: Martha Clarke Takes on Colette’s Chéri and Herman Cornejo interview

Chéri is at the Signature Theatre through Dec. 29.

marthaclarke.com

www.signaturetheatre.org

www.hermancornejo.com

Herman Cornejo interview with Marina Harss in 2012

Novels are treacherous terrain for choreographers. So much of what draws us into a book and imprints itself in our imagination – the atmosphere, the inner lives of the characters, their way of expressing themselves and the complicated byways of their thoughts – is almost impossible to convey in the language of the body. The body does, but only a small fraction of the universe of a novel consists of action. That said, some adaptations of literature work marvelously well. Some, like Frederick Ashton’s A Month in the Country, are even better than their literary sources. Ashton’s affection for its central character, Natalya Petrovna – a bored, empty-headed country aristocrat caught in a passion-less marriage – renders her infinitely more touching than she appears in Turgenev’s play.

Despite the pitfalls, the attraction of literature is strong. In Chéri, Martha Clarke’s new work for the stage, the veteran choreographer and theatre director takes on Colette’s belle-époque portrait of a Parisian demimondaine nearing the end of a long, fruitful career. The stars of her adaptation are the ballerina Alessandra Ferri, who retired from American Ballet Theatre in 2007, Herman Cornejo, one of the great male ballet dancers of our time (and a member of ABT), and the actress Amy Irving. Irving acts as the story’s narrator; neither Ferri nor Cornejo speak. The musical accompaniment is a collage of piano pieces by Poulenc, Ravel, Debussy, and the lesser known Federico Mompou, stylishly and sensitively played onstage by the pianist Sarah Rothenberg. Chéri is at the Signature Theatre through Dec. 29.

Chéri Trailer

Colette’s tale comes in two segments, Chéri and La Fin de Chéri, written in 1920 and 1926 respectively. (The first is in part a retelling of Colette’s own affair with her stepson, Bertrand de Jouvenel, whom she seduced at sixteen.) Clarke, a founding member of Pilobolus, is known for works that cross the line between theatre and dance, often, as in her Garden of Earthly Delights and Tiepolo, inspired by images from art history. (She has also directed quite a bit of opera.)

On the surface of it, Chéri is a simple story. At forty-nine, Léa de Lonval (born Léonie Vallon) leads the well-appointed life of a “courtisane bien rentée…à qui la vie a epargné les catastrophes flatteuses et les nobles chagrins…[qui] aimait l’ordre, le beau linge, les vins muris, la cuisine réflechie.” (A courtesan with a healthy annuity, who had been spared life’s flattering calamities and exalted sorrows…[a woman] who loved order, fine linen, well-aged wines, and sophisticated cuisine). Her lover, Fred Peloux, aka Chéri, is the twenty-five-year-old son of a former corps-de-ballet girl at the Paris Opéra. Now, like Léa, she is a wealthy dowager and Léa’s “best friend,” always ready with a sweetly-worded insult. Chéri, who has grown up in this luxurious, almost exclusively female milieu – like an exotic bird in a silver cage – is spoiled, over-sexed, vain, and cruel in a mindless, almost innocent way. (In this, he resembles his creator, for whom hedonism, according to her biographer Judith Thurman, was a kind of faith.) He is even prettier than Léa.

© 2013 Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

Léa and Fred have been lovers for five years. Now, at twenty-five, it is time for him to settle down and arrange a good marriage. His mother and Léa choose the perfect girl: pretty, docile, and rich. The lovers bid farewell, but Chéri, feeling trapped, returns for one blissful but decisive night. Their affair will not recover its previous insouciance. In La Fin de Chéri, the years have passed. Fred has fought in the First World War and returned a broken man. Léa has moved on; she’s fat and content. He spirals into despair, and the inevitable happens.

In 2009 there was an unsatisfactory movie adaptation by Stephen Frears, which captured the period style but reduced the plot to a wistful bit of frou-frou. Martha Clarke has gone in the opposite direction, and in so doing, taken certain liberties, some of which stem from casting choices. Colette’s Léa oozes a well-earned sense of ease and self-satisfaction; she is rightfully proud of her “pale, statuesque body, tinted with pink, endowed with long legs and a straight back like a nymph in an Italian fountain, a dimpled behind, and high breasts.” Alessandra Ferri, one of the great dramatic ballerinas of recent memory, is small and highly-strung, like an exposed nerve. In the book, Léa betrays weakness only once, and quickly conceals it; Ferri’s interpretation is heavy with loneliness and a kind of desperate sadness, verging on self-destruction. Vibrating behind her characterization of Léa, one senses Ferri’s hunger for self-expression. Chéri marks her return to the American stage after seven years, and coincides with the end of her marriage. She has said that life away from the stage was difficult. A lake of pent-up emotion and energy flows into her performance.

© 2013 Joan Marcus. (Click image for larger version)

Cornejo’s Chéri is also quite different from the character drawn by Colette, more generous, and more gentle. As when he dances the princely roles in Swan Lake or Giselle, there is a kind of modesty and selflessness in his performance. His focus is directed outward, toward his partner. And thus, the emphasis of the story shifts. This change of mood is also reflected in the set designs. Colette describes Léa’s room as pink, gay, and opulent, with double layers of lace over the windows, gilt furniture, and lamps veiled with rose-colored shades. In short, a room made for giving and receiving pleasure. Here, however, Léa’s apartment is painted in a washed-out blue, sparsely furnished, unlovely. The hallway looks draughty. Nothing hangs on the walls. In a sense Clarke has left Colette behind and turned Chéri into something else: an evolving, intimate pas de deux, colored by the personalities of her collaborators.

A few days ago, I asked Cornejo about the creation of the work. Here is an edited version of our conversation, translated from Spanish (Cornejo is Argentine):

MH: How did you become involved in Chéri?

HC: Over a year ago, we were rehearsing Paul Taylor’s Black Tuesday at American Ballet Theatre. Martha was walking by the studio and stopped to watch from the doorway. Afterwards she came up to me and said, “I never do this, but I was really moved by what I just saw. I would like to work together.” Then, a few months later, she had the idea of doing Chéri. First she called Alessandra and then she called me.

MH: How was the piece developed?

HC: We started about a year ago. We worked whenever I was free. Sometimes it was just Mondays, or after seven in the afternoon. Then, when Signature Theatre signed on to present the work, we were able to rehearse for two or three months in the theatre. At the beginning, we would go to the studio without a plan, without preconceptions, and read the book together. A word or a phrase from the book would inspire us, and we would start creating steps to express the emotions in that line or word. From the beginning, Alessandra and I had amazing chemistry and that’s why we were able to go as far as we did. We all made it together.

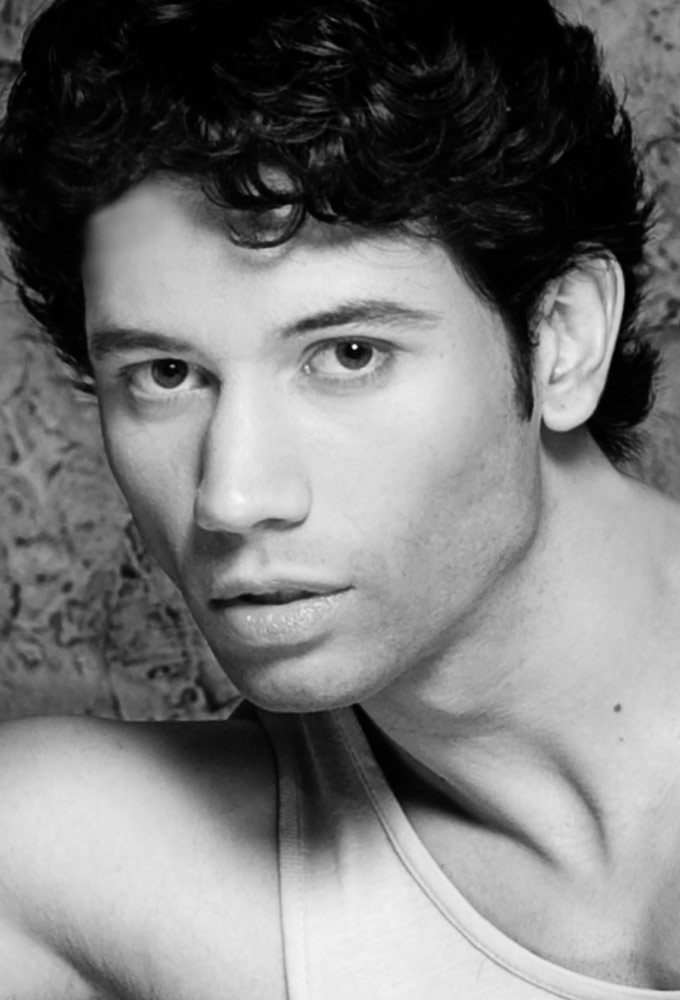

© Manuel de Los Galanes. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Did Martha Clarke have an idea of what she wanted?

HC: She left the door open for us to interpret the characters. She told me that I had a much more masculine, muscular way of moving than the actor who played Chéri in the film, and that she didn’t want to lose that quality. She encouraged me to use my own physicality and feeling for the character, which was slightly more masculine than in the book. But we did it all together, down to choosing the music. In some rehearsals, we would just listen to music. She wanted to use certain composers, and we selected the pieces together. We built the story through the music. The same thing with the stage designs. As we rehearsed, we would say, “we need this here, and that there.”

MH: Did you know Ferri before working with her on Chéri?

HC: I knew her from ABT because when I arrived [in 1999] she was one of the great ballerinas and she and Julio Bocca were the ideal couple onstage. Actually, Bocca sent Alessandra a funny message before our first performance of Chéri, wishing her luck and saying that he was a bit jealous that she had found a new Argentine man. [Bocca was a mentor of Cornejo’s and instrumental in bringing him to ABT.] Before now, she and I had barely ever shared a stage. She mentioned at some point how surprised she was by our chemistry, because even though she knew I was a great dancer, she still thought of me as the sixteen-year-old I was when I first joined the company.

MH: In Chéri, there is a very beautiful scene with a mirror, which I don’t remember from the book. Ferri appears in the mirror, like a memory, looking very lovely, with her shoulders exposed.

HC: It’s not quite the same in the book. Chéri can’t get Léa out of his mind. He’s completely stuck, attached to that period in his life when they were together and when she was young. Now she’s old, and fat, and happy with her new life. He visits a friend of Léa’s who tells him stories about her and shows him photos. The scene with the mirror is an allusion to that, as if he were looking at old photographs.

MH: When you dance a big role at ABT, there are several days between performances, but here you’re performing night after night, for over a month. Is that difficult?

HC: Physically it’s not too difficult, but we’re finding that emotionally, it’s devastating. Especially on days when we have two shows. It can be a bit hard, emotionally, especially the final ten minutes, my solo. It takes some time after we finish, backstage, for me to feel ready to interact with people. But the positive thing is that because we do so many shows, we don’t need to “prepare.” It becomes part of your life. And that gives you the freedom to make every night different. No two performances have been the same. Even when something doesn’t work perfectly, it doesn’t feel “wrong,” we just go with it. Each performance has a different color.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

MH: Over the past year, you’ve had some extraordinary roles created for you: the spirit in Alexei Ratmansky’s Symphony No. 9, Caliban in his Tempest, and now Chéri. What has that been like?

HC: This year has been a highlight of my life. In The Tempest, it was incredible to create a character who is so different from what I do, from who I am. Even though Caliban doesn’t have that much time onstage, he makes quite an impact. Unfortunately I don’t know if I’ll be able to perform it much longer, because it’s very hard on the knees – he spends a lot of time on the ground. And now, Chéri. This role is very close to my heart. I don’t know how to describe it, maybe it’s a bit like when Spectre de la Rose was created for Nijinsky. A role imagined specifically for him. I’ve been lucky to dance it with Alessandra. That was what convinced me to take this on, because in a way, the idea of being onstage without using my technique was a step into the unknown. With her, I know we can rely on each other. I was lucky that my first time was with such an incredible group of artists. I think Martha has created something exquisite.

You must be logged in to post a comment.