© Julieta Cervantes. (Click image for larger version)

Contemporary Dance at the Hong Kong Arts Festival

Trisha Brown Company

Rogues, Les Yeux et l’âme, Foray Forêt, Set and Reset

Hong Kong, Academy for Performing Arts, Lyric Theatre

21 February 2014

www.trishabrowncompany.org

Akram Khan Company

iTMOi (In the Mind of Igor)

Hong Kong, Cultural Centre Grand Theatre

6 March 2014

www.akramkhancompany.net

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch

Iphigenia auf Tauris

Hong Kong, Cultural Centre Grand Theatre

12 March 2014

www.pina-bausch.de

Hong Kong Jockey Club Contemporary Dance Series Programmes 1 & 2

Hong Kong, Cultural Centre Studio Theatre

15 March 2014 (matinee & evening)

Review of Ballet at the Hong Kong Arts Festival 2014

A version of this review previously appeared in the South China Morning Post

The 2014 Arts Festival offered contemporary dance from established international masters along with new wave work from Asia, Scandinavia and Hong Kong itself. I didn’t make it to everything – too little time, too many shows. Those I did see were a mixed bunch which offered illuminating examples of the contemporary genre’s strengths and weaknesses.

First up was Trisha Brown, one of the key figures of modern dance in the United States since the 1960s. An artist as well as a dancer/choreographer, she is known for her frequent collaborations with avant garde artists and composers, notably Robert Rauschenberg and Laurie Anderson.

Brown’s company had not appeared in Hong Kong since 1988 so this was an important opportunity for local audiences to discover her distinctive style.

The opening programme offered 4 pieces, starting from 2011 and moving back through the 1990s to the 1980s. All demonstrated Brown’s celebrated fluidity of movement, which has a strikingly natural quality, it looks like a genuine extension of normal movement rather than something contrived by a choreographer for the sake of it – her musicality and her fine visual sense. However, while the programme was well-danced and aesthetically pleasing, there was a certain lack of substance.

Interestingly, although the earlier works are considered among Brown’s “masterpieces”, it was the later ones, created when Brown was in her 70s, which proved more satisfying, with a purity which showed the choreographer’s art stripped down to its essence.

© Stuart Shugg. (Click image for larger version)

Rogues is a duet for two men who echo and occasionally interrupt each other’s movements, now one leading, now the other. Set to a score by Alvin Currant, the piece is beautifully paced, starting slowly and building to an effective finale.

Les Yeux et l’âme (The Eyes and the Soul) is a suite for four couples developed from Brown’s choreography for Jean-Philippe Rameau’s 1745 opera Pygmalion. The piece has a limpid elegance and charmingly solemn playfulness which go perfectly with the baroque score. The graceful juxtaposition of bodies in duos, trios or with all eight dancers together is exceptionally pleasing. The piece is further enhanced by Elizabeth Cannon’s costumes which match the simplicity and flow of the movement.

© Stephanie Berger. (Click image for larger version)

The 1990 Foray Forêt is famous for the conceit of having the dancers on stage while a marching band (always locally recruited, in this case the Ying Wa Primary School Senior Band) circles the auditorium outside, playing. The music fades in and out as the band passes the entrances to the theatre, so the dancers sometimes perform to music, sometimes in silence. While this disconnect between sight and sound may be intriguing at first, by the third time the music comes around the interest wears thin. It also seems unfair that the band (who did an admirable job) do not get to take a bow. The best aspects of the piece are a powerful solo at the end with impressively long-held balances (originally danced by Brown herself) and Rauschenberg’s elegiac, autumnal designs.

Set and Reset is another collaboration with Rauschenberg, created in 1983 to a score by Laurie Anderson. Three geometrical shapes are suspended above the stage with a rapid succession of black and white video from different eras of the 20th century projected on them while the dancers perform beneath. No doubt this use of multi-media was innovative and cutting-edge at the time, but it now looks dated and for anyone not equipped with two pairs of eyes, the video distracts and detracts from the dance.

Nonetheless the programme as a whole proved that Brown is indeed that rare beast – a distinct, original choreographic voice.

There was a chance to compare her work with that of another grande dame of 20th century dance, Pina Bausch, whose Tanztheater Wuppertal performed her 1974 dance version of Gluck’s opera Iphigenia in Tauris. Bausch is a choreographer you probably love or loathe – the best prize I can offer for guessing which camp I belong to would be not having to sit through an evening of her work.

Where Brown responds to Rameau with lightness, elegance and wit, Bausch’s Gluck has the subtlety of a sledgehammer, every phrase of the libretto laboriously translated into movement. The choreography for Iphigenia made me think of a friend’s comment on another Bausch piece that it looked “like a shampoo commercial”. Ruth Amarante undoubtedly has lovely hair (I would have been happy to know what conditioner she uses) but tossing it endlessly is no substitute for actual dance.

© John Ross. (Click image for larger version)

Image from John Ross Balletco photoshoot at Sadler’s Wells in October 2010.

The best moments came from Iphigenia’s brother Orestes (Pablo Aran Gimeno) and his friend Pylades (Fernando Suels Mendoza) who both managed to generate some emotion despite the heavy-handed homo-eroticism of their duets, with both dancers clad in skin-tight flesh-coloured underpants.

Humour is not this work’s strong suit, but unintended comic relief arrived in the form of the villain of the piece, King Thoas. The forward-tilted, off-balance walk, the hands curved backwards, the glazed, glaring eyes reminded me of someone, now who could it be… Then enlightenment came: Mr Bean.

The compensation of the evening was the music, beautifully performed (with the singers placed upstairs at the sides of the circle) by the soloists, the Hong Kong Arts Festival Chorus and the Hong Kong Sinfonietta orchestra under the baton of Jan Michael Horstmann.

Akram Khan has been a regular visitor to Hong Kong in recent years with his solo performance masterpiece Desh and his collaborations with international divas Sylvie Guillem and Juliette Binoche. This time it was the turn of Khan’s company, made up of 11 dancers from a variety of countries and dance backgrounds, with a much-praised new piece.

© Louis Fernandez. (Click image for larger version)

iTMOi (In the Mind of Igor) was created in 2013 at the request of Sadlers Wells to mark the centenary of Igor Stravinksy’s The Rite of Spring. Rather than create a piece set to the original music, Khan commissioned a new score by three different composers, Nitin Sawhney, Jocelyn Pook and Ben Frost with the concept of drawing inspiration from Stravinsky’s ground-breaking work and gaining a deeper understanding of how he achieved it. Hence the title, as choreographer and composers seek to enter the master’s mind and break new ground themselves.

Khan has also drawn inspiration from the original work’s theme of primitive ritual and human sacrifice. In Nijinsky’s version, a Chosen Maiden is forced to dance until she dies as part of a tribal rite to ensure that spring and fertility return to the land. Khan is more oblique in his approach – the piece opens with quotations from the Biblical story of Abraham being commanded by God to sacrifice his son Isaac, a young girl dressed in white appears to be the chosen victim but it is a man who tried to save her who is ultimately killed.

The work is admirably ambitious – perhaps too much so for its own good. It certainly makes tremendous theatre, many individual segments are extremely powerful and the dark, brooding atmosphere with flashes of brutality is a fitting tribute to The Rite of Spring. There is much ambiguity – a man in black who may be God, a woman in white who may be the Earth Mother and a slinking figure with horns who may be the Devil or just an animal. However, the piece suffers from a lack of structure and the overall effect is more confused than profound (ambiguity can be irritating as well as intriguing).

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

The choreography draws inventively on the many disciplines from which the dancers come – as the programme acknowledges, they themselves created much of it – and the whole cast perform with passion and commitment. Stand-outs include the blazing energy of Christine Joy Ritter, Nicola Monaco’s glorious sinuosity of movement as the horned figure and Denis Kuhnert’s brilliant use of moves derived from break-dancing. The score is strong (a pity there is no way of knowing which composer was responsible for which part), Kimie Nakano’s costumes are well-imagined and Fabiana Piccioli’s lighting design is absolutely stunning.

In contrast to the big international companies, for the third year in a row the Festival presented two programmes of new work by local choreographers, sponsored by the Hong Kong Jockey Club. (For those unfamiliar with our rather strange city, Hong Kong has two horse racing tracks and all betting – well, legal betting, anyway – goes through the Jockey Club which then ploughs back much of the resulting massive revenue into community projects including support to the arts.)

Without doubt a valuable opportunity to nurture new talent, it must be said that the overall results of the series have been mixed in quality. This year’s crop had good moments, but the choice of work was disappointingly limited – five pieces were on offer, of which one was included in both programmes and two were almost identical in theme.

The work also underlined the lack of variety which plagues so much Hong Kong contemporary dance. The vocabulary of movement is too limited and too often the same (is there ever a piece where no-one falls down on their back and waves their legs in the air?). The juxtaposition of a solo or duet front stage while another dancer moves slowly along the backcloth is fine in itself but not when it features in piece after piece. There is an increasing trend to use dialogue instead of movement to express ideas – dance should be able to do without this. And why, oh why are there always chairs?

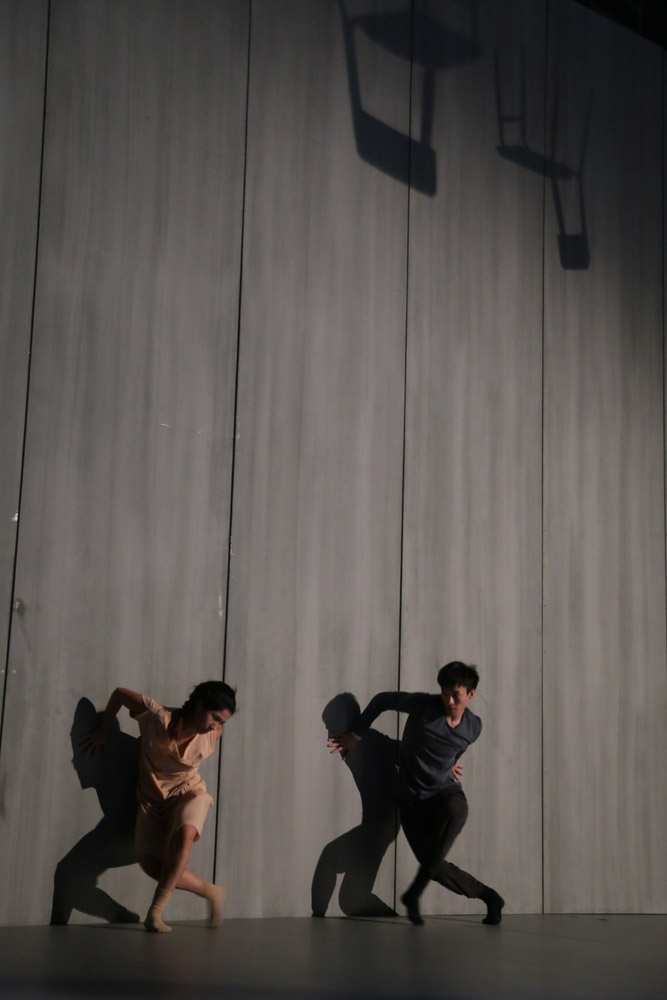

© Keith Hiro. (Click image for larger version)

The most satisfying of the five pieces on show was Ivanhoe Lam Chun-ho’s Even – Odd. Three dancers dressed in white, two male and one female, compete for possession of a bottle of water and a glass, around which a succession of solos, duets and trios lead into one another. This ongoing struggle is observed and occasionally interrupted by an elegantly dressed Chinese opera artist (Geng Tianyuan) who sings and in one charmingly whimsical section brandishes a furled white umbrella like a traditional operatic sword. There is a strong duo for the two male dancers and a wittily choreographed fight over the water between girl and boy.

The work has strong visual effects – Goh Boon-an’s stunning lighting projects the performers’ silhouettes like shadow puppets and the all-white costumes lend a dreamlike quality.

Lively and entertaining, this was a well-crafted piece with good performances by the three dancers (Lim Wei-wei, Liu Heung-man and Bruce Liu) as well as the benignly authoritative Geng. Lam gets extra marks for using a chair only once, when Geng sits on it at the end to drink a cup of tea.

Two choreographers produced duets which explored the difficulties of communication between man and woman. Puzzle was choreographed by Huang Lei and danced by him with Gigi Yang, who was making a welcome return to the stage after maternity leave. The piece consists mostly of solos – the final section when the two dance together is the strongest, with some complex doublework. The choreography is rather too busy and yet again a chair plays an unnecessarily prominent role. However, the relationship between the protagonists is intriguing and the brief moments of tenderness when they manage to communicate are touching.

Above all, Yang and Huang are two of Hong Kong’s finest dancers – their speed, control and attack were a pleasure to watch. They are also old friends who both became parents for the first time last year and while the piece was not outstanding, it had an appealing emotional resonance and depth.

© Keith Hiro. (Click image for larger version)

Xing Liang’s Reaction was more aimed at the intellect than the emotions. Xing is by far the most experienced of the five choreographers and the piece was smooth and assured but oddly uninspired. The choreography featured the convoluted, spiky yet flowing arm movements characteristic of Xing’s work along with some complicated lifts. There was a lot of standing on (yes, you guessed it) chairs and two more chairs were suspended upside down above the stage for good measure. Although there were good moments there was little structure – basically the work meandered on until it stopped. A disappointment from a choreographer of Xing’s ability.

Also disappointing was Outspoken, the first solo piece by Yang Hao, a promising young choreographer who was involved in some of the best work in the two previous Jockey Club seasons. Sadly, Yang seemed out of his depth – his performance was heartfelt but ideas were lacking and the whole effect disjointed. The appearance of a man in a plaid shirt who sits down (on a chair…) and proceeds to read the same text in Cantonese over and over again while Yang dances did nothing to improve matters.

© Keith Hiro. (Click image for larger version)

Chloe Wong’s Heaven Behind the Door was a well-meaning attempt to explore the current climate of political angst in Hong Kong. Alas, while the intentions were good the execution was inept, with far too much dialogue instead of dance and weak choreography when there was dance. The projected image of a fish swimming desperately round and round a small bowl of water while the dancers ran round the stage was presumably meant to symbolize Hong Kong’s plight. This clever lighting effect was the best thing about the piece although the fact that it was a real fish, live on stage (if not for long) made it not for the squeamish. Still, at least there weren’t any chairs.

You must be logged in to post a comment.