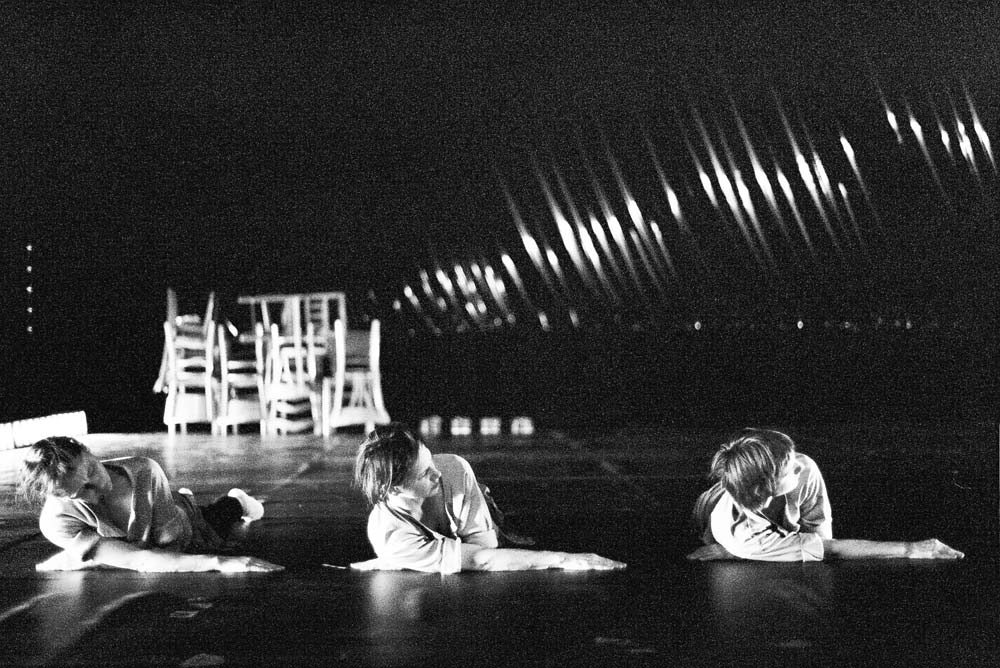

© Jean-Luc Tanghe. (Click image for larger version)

Rosas – Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Rosas danst Rosas

New York, Gerald W. Lynch Theatre

12 July 2014

www.rosas.be

lincolncenterfestival.org

Girls Will be Girls

To say that the early works of the Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker are repetitive is merely to state the glaringly obvious. As with the music of the American Minimalist composers, endless repetition – with minute variations – is an essential compositional feature. Minimalism was in the air when De Keersmaeker started her dance-making career. Her Fase: Four Movements, was composed in New York in 1982; it used a series of musical pieces by Steve Reich that consisted of looping phrases that went in and out of sync. Six years earlier, Lucinda Childs had collaborated with Philip Glass and Robert Wilson on Einstein on the Beach, a four-hour epic built out of loops of text, rhythm, movement.

In a kind of mini-retrospective, four of De Keersmaeker’s earliest works are being presented by the Lincoln Center Festival this summer. Fase was performed earlier in the week. Next came Rosas danst Rosas (1983) perhaps the most famous of them all. Its enduring prominence is due in part to the fact that it was filmed in 1997, each section set in a different zone of a prison-like school in Leuven. (The movie, by Thierry De Mey, is available in several parts on YouTube.) More recently, the pop star Beyoncé “borrowed” choreography from the film of Rosas danst Rosas in one of her music videos. De Keersmaeker’s company, Rosas, will perform Elena’s Aria (1984) and Bartók/Mikrokosmos (1987) next week.

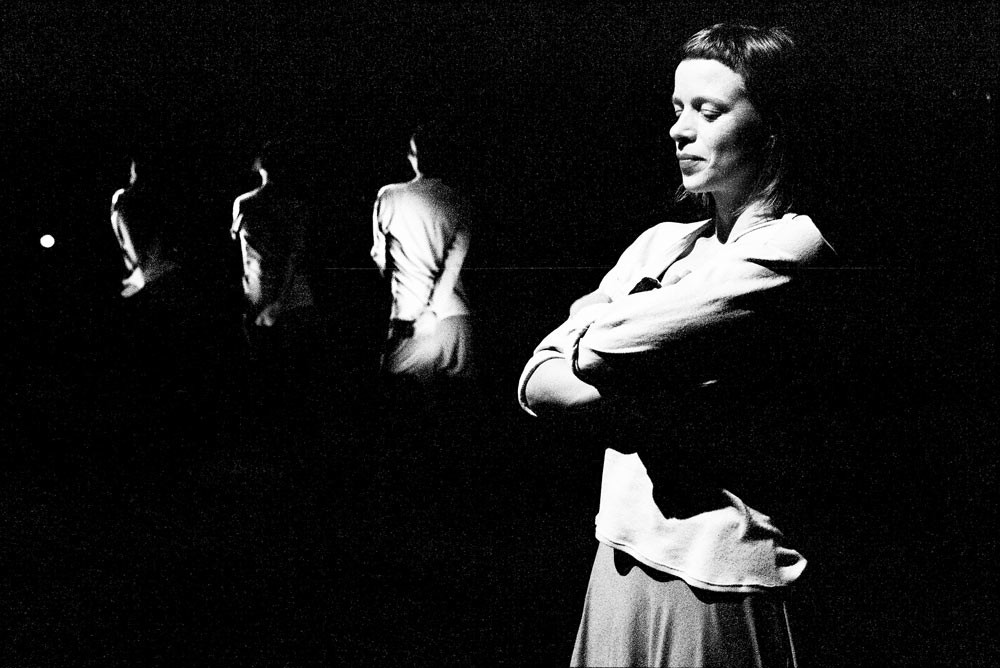

© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

Watching Rosas danst Rosas this weekend it was easy to understand why it still stands as a prime example of De Keersmaeker’s choreographic approach. Like Mark Morris’s Gloria or Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, it’s one of those works that immediately announces a highly individualized style. In this case, the style is characterized by sharpness, speed, rhythmic alertness, and almost manic precision. The piece begins in near-darkness. A dancer walks on, then another, and then two more. As in Fase, they are all women. They face the rear of the stage, tilt, and fall to the ground, where they roll and breathe in unison, almost like pistons in a machine, until finally one of them breaks away and begins to move in partial counterpoint to the others. Later they will sit in chairs, cross and uncross their legs, bend forward, or, once erect, pivot and swing their arms, balance on the tips of their toes, lunge, and glide. Most of the movement travels either side to side, or forward and back, or, in the final section, in a circle around the stage. No-one touches.

But what distinguishes the goings-on as pure De Keersmaeker isn’t so much the precision and the rigor – though these are essential – as the types of gestures that punctuate the simple and often-repeated movement phrases, and the spirit in which they are executed. From the start, there is an underlying note of tension, a “mean girl” hostility that seems to emanate from a tightly-wound sexuality. The dancers look like women – tall, lean, long-limbed, of different ages – but also like girls, or rather like adolescents. They wear a variant of the schoolgirl uniform – short grey skirt and top, black leggings and socks, clunky, nun-like shoes. No makeup. Their long, straight hair is tightly pulled up in a pony tail, at least at first. Again and again, they touch their bangs or swish their hair, delicately place a hand on one breast, pull up their skirts – only slightly – and yank at their shirts. These aren’t sexless or angelic creatures like Lucinda Childs’ endlessly gliding dancers. They are women made out of flesh and blood, mischievous, sexual, often bored, well acquainted with impure thoughts.

© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

In one section they sit in wooden chairs, facing the diagonal; they could be teenagers waiting to be called to the principals’ office, sprawled and petulant, bound by a silent bond of mischief, sharing sly glances. In another, they take turns baring one shoulder and then both, testing out their sexual charms on an invisible – perhaps male – observer, or the mirror. The dancers imbue these little moments with their own individual hue. Sue-Yeon Youn is almost bashful, but curious; Cynthia Loemij is more serious, hard-edged. Tale Dolven is the most brazenly sensual, almost taunting the audience in the shoulder-baring sequence. Unsurprisingly, De Keersmaeker’s take on her little seduction scene – she’s performing in some of the shows – has many layers, a fascinating mix of sarcasm, private pleasure, and playfulness. She seems to be dancing mainly for herself.

Which isn’t to say that at over ninety minutes, Rosas danst Rosas doesn’t feel rather drawn out at times. Long stretches proceed in silence, punctuated only by the dancers’ sharp breaths. Others are accompanied by ticking sounds or repetitive rhythmic patterns composed by Thierry De Mey and Peter Vermeersch. The mind wanders, and more than one person within earshot breathed a sigh of relief when one section finally transitioned into the next. The ending is weak. In many ways it’s the maddening creation of an obsessive imagination. But it’s one of those works that leaves its little imprint on the mind’s eye.

You must be logged in to post a comment.