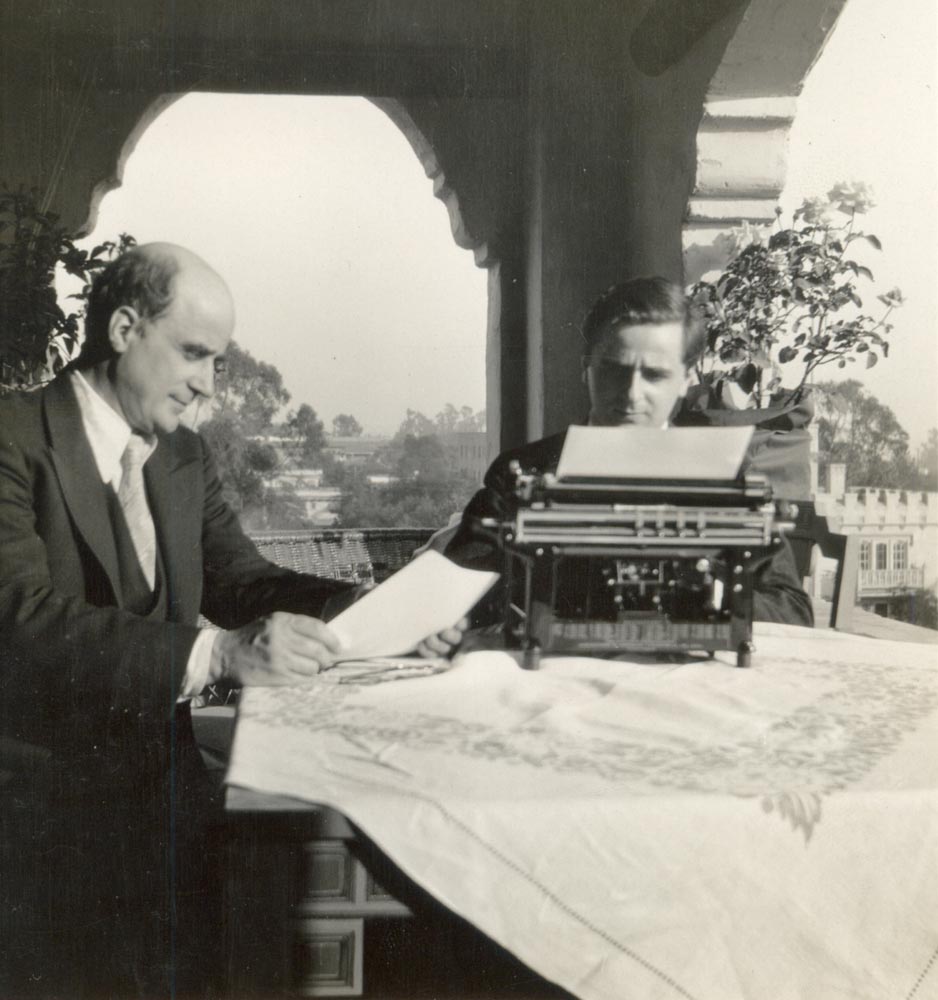

© & courtesy of Isabelle Fokine and Fokine Estate Archive. (Click image for larger version)

Born in Paris in 1958, Isabelle Fokine is the daughter of Vitale Fokine and granddaughter of choreographer Mikhail Fokine. She is artistic director of the Fokine Estate Archive, which holds the worldwide copyright to his work.

She began her ballet training with her father and went on to Ballet Theatre School in New York. She performed with the Bolshoi Ballet and American Ballet Theatre until reoccurring injuries ended her dancing career. In the latter years of his life, Isabelle assisted her father as he recreated the Fokine repertoire for companies around the world. In 1994, she began an association with the now Mariinsky Ballet in an effort to restore the ballets of her grandfather to his homeland.

Here she answers questions put to her by Paul Arrowsmith.

Why revive Mikhail Fokine’s ballets? Are they historical curios or works that are theatrically alive today?

Interest in them has stood the test of time. A hundred years on, they are still performed and revived regularly. Over the last 20 years, evenings devoted exclusively to Fokine’s work have become popular. They are very much alive.

Given everything subsequently in dance, can Fokine’s revolutionary aspects still make an impact?

His revolutionary impact is in every dramatic ballet created over the last century. It is invisible because it is present everywhere. Whenever the drama in a ballet is told through dance and movement rather than mime, whenever the costumes and décor are accurate to period and character, whenever there is unity of all the arts towards creating one artistic picture, you are seeing the influence of Fokine.

Imagine Romeo and Juliet or Le Jeune homme et la mort created in the time of Petipa. Fokine’s influence on Cranko, MacMillan, Robbins, Petit, Ratmansky – to name a few – is ever present. With regard to the impact of Fokine’s individual ballets, something very odd has happened. Because they are seen as ‘old’ and therefore historical, they are often presented in a way which is in complete contradiction to Fokine’s original ideals.

For example, Les Sylphides is seen as a ‘white ballet’ and now performed as if it were a classical work. In fact it was meant to revive the romantic era, but filtered through my grandfather’s reforms. So while there is an essence of Marie Taglioni, there are revolutionary elements throughout. My grandfather broke the idea that classroom technique be performed on the stage. Any movement in his ballets would no longer go from preparation to position. Positions should flow from one movement to another. However, there are productions that have removed this element. Having been cleaned up, consequently the ballets appear more conventional.

© & courtesy of Isabelle Fokine and Fokine Estate Archive. (Click image for larger version)

What could choreographers working today learn from Fokine?

Nothing in a Fokine ballet is pointless. Nobody ever just appears onstage or dances a variation. Every character enters the stage having come from somewhere. They exit to go somewhere else. The wings do not exist. They are just locations the audience cannot see. The fourth wall is never broken to address the audience – except in Carnaval, which is a commedia dell’arte piece.

Beyond the stage, both upstage and down, are horizons the dancer sees beyond within the world of their character. No movement is without purpose, all have reason and intention. An arabesque is not merely a position. It is an attempt to get away, a reach, a longing. Fokine reached for dramatic authenticity in ballet, the way Stanislavsky did in theatre.

What qualities do dancers need to make a Fokine ballet live?

Artistry, musicality, acting ability – in abundance!

Every character in a Fokine ballet has an internal monologue and every movement stems from that internal thought. There are no superfluous gestures. If one is aware of what the dialogue or monologue is, the movements all make perfect sense. They are all based in reality.

Dancers are not trained to approach acting this way. They are more accustomed to indicating dramatic action. However, every single Fokine ballet demands a thinking actor. Much more time is spent in rehearsal on this aspect than on anything else.

What are your sources? I understand there is a large amount of material that your mother catalogued.

There is an enormous amount of material and comes in various forms – notation, film, photos, annotated scores.

With regard to sources, all of the ballets I have restaged so far, are ones in which I have also had direct experience. This means that I learned them from my father, performed in them or was present during their restaging. For all of these I have archival film footage, scores, dance notations, descriptions, photos, sketches …

© & courtesy of Isabelle Fokine and Fokine Estate Archive. (Click image for larger version)

These serve as reminders and reference points. In addition, my grandfather chronicled what he wanted to accomplish with each work, detailing the obstacles, and how he tried to surmount them. With each ballet he had a vision. Sometimes what came to fruition didn’t meet his aspiration. In subsequent productions, he often tried to rectify what hadn’t succeeded. This information is quite interesting and I do make use of it.

For example, in the first staging of The Firebird, there were two knights riding horses. Live animals being unpredictable, they did what came naturally and soiled the stage. When he revived the work with Ivan Bilibin, the knights were painted on glass for their ride projected across the sky. According to my grandfather, the results exceeded his expectation and were far superior to the ‘real’ thing.

When I staged The Firebird in Russia I tried to incorporate this effect. Our designer was unable to make the knights on horseback visible across the backdrop – but I will continue to try to surmount this problem in future productions as my grandfather intended.

I believe there is a Dying Swan ‘bible’, photographed pose by pose and notated. Are there other bibles, for Le Spectre de la rose, for example?

There are, but they don’t all resemble the Swan book because of their size. The other ballets do not use the photo pose-by-pose format, due to the number of dancers involved and length of the work. Instead they often contain sketches outlining positions. The Spectre book does contain many photos, again, due to the smaller size of the work.

Where notation does not exist, can ballets be revived from photos and other fragments?

I suppose it depends on the scope of the material in your possession.

Obviously the less material and experience one has, the further the result is likely to be from the original ballet. Having said that, some repetiteurs have made very interesting use of very limited material. Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring is a case in point.

Given that Fokine is only known by a fraction of his works, among your sources, is there material that would enable the reconstruction of lost ballets, Daphnis and Chloë or his later works, Bluebeard, Russian Soldier?

Unfortunately not the ones you mention but yes, there are others – Paganini, Igroushki ‘Russian Toys’, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Panaderas, Le Coq d’or and several others.

© & courtesy of Isabelle Fokine and Fokine Estate Archive. (Click image for larger version)

How far did your involvement extend in productions such as those by Andris Liepa of Le Coq d’or, Thamar, Le Dieu bleu where new choreography has replaced Fokine’s original?

I have not been involved at all. Andris and I worked together 20 years ago and have not collaborated since. What became clear during our work together is that we have very different views. Our artistic tastes and sensibilities are not at all similar. I have only seen an excerpt of Andris’ Thamar which bore no resemblance to my grandfather’s ballet.

Ballets shift in performance. How do you decide which version to mount?

There is a belief that anything passed down from Diaghilev or the later Ballet Russes companies are somehow more authentic. The problem here is that Fokine himself didn’t believe that to be the case. After he left the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev made alterations to some of his ballets.

The Firebird is a case in point. The production passed down from Sergei Grigoriev [for The Royal Ballet] was one my grandfather disapproved of. As most people know, when Alexander Golovin’s designs were destroyed, Diaghilev commissioned Natalia Goncharova to design a set that would be easier to tour. My grandfather was horrified by the result – “It dealt a death blow to my ballet.” This was due to the fact that dancers were reacting to elements of the staging no longer present.

This may not have troubled Diaghilev, but to a choreographer for whom dramatic sense was paramount, Fokine believed it made nonsense of his work. There are other instances affecting his choreography. Diaghilev had Nijinska make changes to Polovtsian Dances. My grandfather greatly resented his ballets being altered. Today nobody would dream of tampering with the work of a living choreographer, so it seems inconceivable that it took place, but it did – often.

© & courtesy of Isabelle Fokine and Fokine Estate Archive. (Click image for larger version)

With Petrushka, different dancers have made alterations to the choreography during their interpretations. When researchers look to recordings for their knowledge of a ballet, they need to be conscious of how removed that may be from Fokine’s original work. For example, the Joffrey Ballet production by Léonide Massine and Yurik Lazowsky was wonderful in their original live performances. When it was filmed with Rudolf Nureyev, he was at the end of his dance career. As a result he made changes to the choreography to suit his physical abilities and very personal acting choices, taking numerous liberties with the role.

And in Paris, the production of Petrushka is Nicholas Beriozoff’s version “based on Fokine’s”. In fact he made so many changes that he requested that we – the Fokine Estate – gave him permission to copyright it as his own ballet. So Beriozoff did not claim this to be an accurate rendition, quite the opposite.

How much in demand are Fokine’s ballets, those we tend not to see as much of, say Carnaval?

Yes, of course but I rarely suggest ballets to companies. They make their own choices. Interest in particular repertoire is cyclical. A number of circumstances need to come together to make a ‘rare’ revival possible.

For several years I was in discussion with repetiteur Airi Hynninen. She is a specialist in my grandfather’s ballet L’Épreuve d’amour. We were both keen to get a production done. In the end, she finally staged it in Korea. Their interest in the ballet was connected to its libretto, but it seemed a long road for a work premiered in Monte-Carlo to great acclaim.

Is the lack of a recent performing tradition an issue?

Russian character dance is no longer part of the vocabulary of most contemporary western ballet dancers. While many dancers will do a bit of character work in say The Nutcracker or Swan Lake, it does not hold the level of importance it once did. With character dance, comes feeling and behaving like an individual ‘earthy’ character.

In Petrushka, the dancers should appear as actors in a film, completely natural, involved in their own lives, spontaneously reacting to what happens around them. This comes more naturally to some dancers that to others. One normally hires actors to perform the non-dancing roles and rehearse them for a few weeks. When given a specific character and a set of actions to fulfill, they usually relish the opportunity.

However, for many ballet dancers if a role is not technically demanding they don’t view it as important. They perceive ‘a walk on part’ as just that, ‘walking on’, instead of a chance to explore another aspect of being a performer.

I also think we’re in a period of ballet history where modern abstract ballet has created a generation of dancers for whom naturalism can be difficult. Having said that, there are always individuals who find this an exciting challenge and rise to the occasion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.