© Tina Sutton. (Click image for larger version)

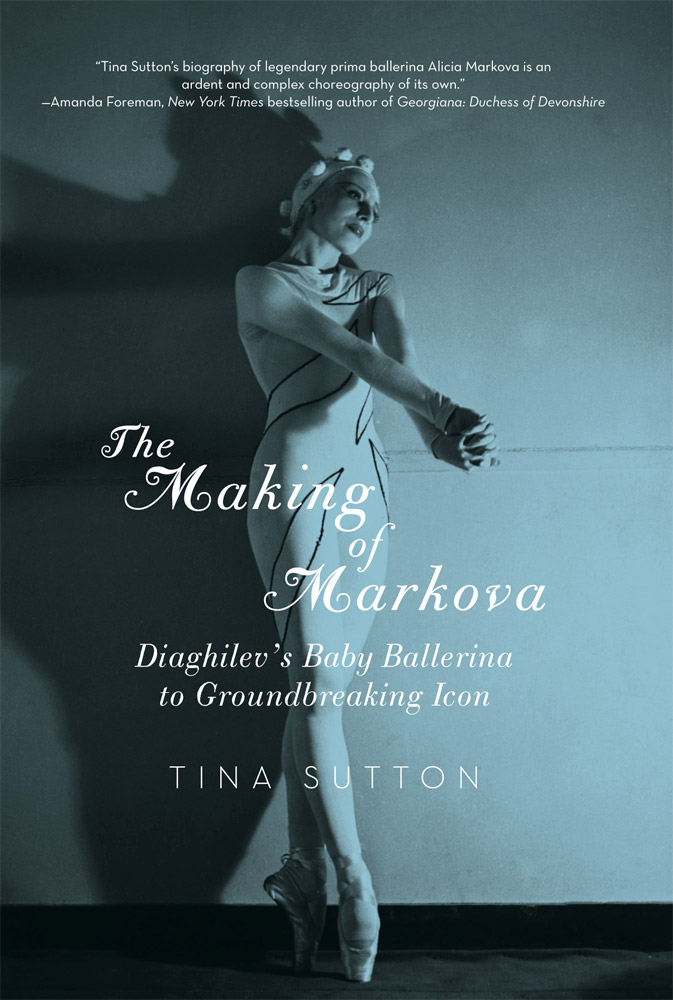

The Making of Markova: Diaghilev’s Baby Ballerina to Groundbreaking Icon

Pegasus Books

Published in paperback 2 September, at £12.99.

Publishers page

Markova Archive at Boston University Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center

Tina Sutton is keen to point out that her book is about the making of Alicia Markova’s career as a world-famous ballerina, not her life story : ‘It’s not a complete biography because she lived on for four decades after she retired from dancing. I wanted to show how she became the woman she was, how she managed her life as a dancer. I never met her – I never saw her perform – but from her archives I found out a lot about who she was during the time she was dancing’.

Sutton, who is not a dance writer but a fashion journalist for the Boston Globe, volunteered to sort out the 137 boxes that Markova had given to the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University. Some of the material came in 1989 from a warehouse store the ballerina kept in Brooklyn; the rest was sent from her Knightsbridge flat after Markova’s death in 2002. Why Boston rather than London? ‘Well, Vita Paladino, the archives director, approached her – and since you ask, no money was involved. The Gotlieb Centre has an international reputation for archiving and displaying collections given by significant individuals, and Markova wanted to make sure her ballet memorabilia would be available to everyone, not just historians and researchers.’

© Pegasus Books. (Click image for larger version)

According to Sutton, the bequest was typical of Markova’s mission to bring the joy of ballet to as wide a public as she could. ‘That’s why she toured so much to out-of-the-way places and countries that had never seen ballet. She performed to huge audiences in sports arenas and concert halls as well as the Hollywood Bowl. It may sound very zealous but she truly believed ballet should be for everyone. And she kept everything. Valuable mementoes, like Pavlova’s shoes, plus masses of photos, all her programmes, cuttings, letters from fans as well as famous people, transcripts and tapes of interviews she’d given – a treasure trove for a biographer’.

Sutton was originally asked to write a brief account of Markova’s career for the Gotlieb Centre but soon realised that her subject’s life, personal and public, was so fascinating that she undertook a substantial biography. She decided to rely entirely on material that she could verify, either from Markova’s collection or from contemporary accounts in print. ‘I couldn’t trust people’s memories from so long ago – the stories changed over time and I know from letters in her archive that some of the anecdotes couldn’t have been true. I wasn’t prepared to speculate about anything I couldn’t prove. What I found out was entertaining enough’.

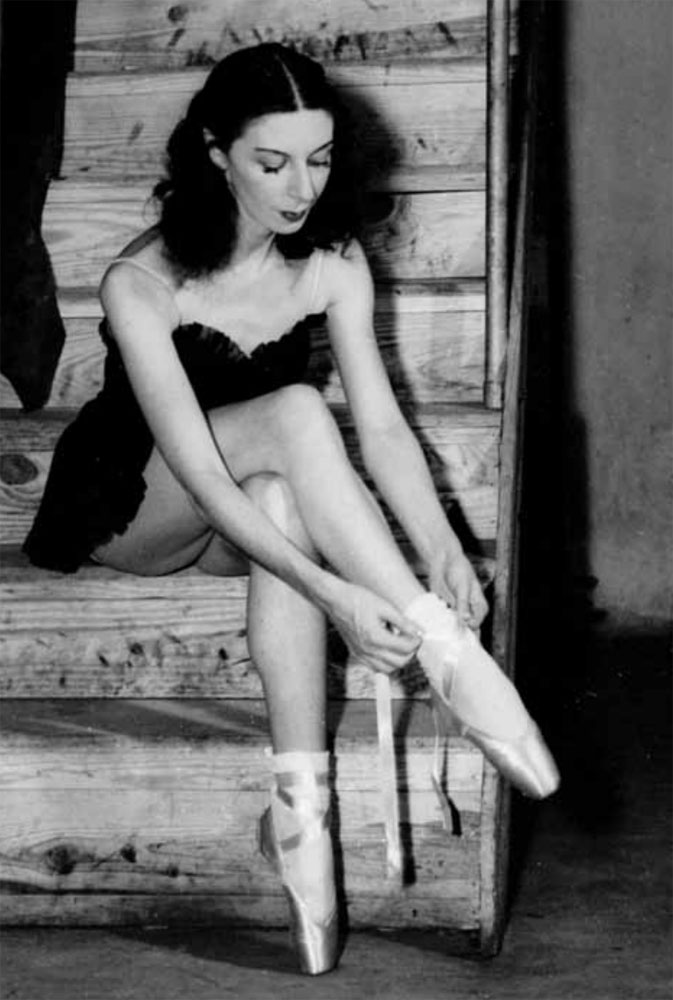

One of her most touching finds was young Alicia’s pink-covered autograph book. (Her first name – actually her second, after Lilian – really was Alicia, not Alice Marks, which made better newspaper copy.) As photographs show, Alicia at 14, when she joined Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, looked even younger in her long white socks. ‘She was a starstruck fan. She went to each dancer in the company to ask for an autograph, curtseying to them, and she kept scrapbooks where she pasted photographs of her favourites. Her governess kept them and sent them home, where her mother hung on to them as the family moved from place to place. The boxes even survived the bombing of their house during the war, and ended up in storage in New York. I opened them in Boston some 80 years later’.

Picture courtesy Pegasus Books, Markova Archive, Boston University Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center (©)

Alicia’s sisters, Doris, Vivienne and Berenice (Bunny), kept albums of her reviews and interviews over all the decades she was performing. The last surviving sister, Vivienne, who married the balletomane Arnold Haskell, willingly gave Sutton permission to use the archival material, pleased that someone was so enchanted by Alicia. ‘Of course I empathised with Markova’, says Sutton. ‘ I read her diaries and letters, I listened to tapes of her radio interviews, so I knew what she sounded like when she was in her prime – that light-pitched voice, still vivacious. Of course I was on her side’.

Sutton is indignant on her subject’s behalf about the treatment Markova received in England after Diaghilev’s death in 1929. She was stranded in London, aged 19, virtually penniless and longing to dance. But when the Camargo Society was set up to provide an opportunity for British ballet to develop, she found herself virtually excluded. Sutton cannot understand why, unless it was the anti-semitism and jealousy shown by Lydia Lopokova, one of the prime movers of the Society. Although Markova’s name figures in histories of the Camargo Society, she was not invited to the inaugural dinner nor to take part in early performances. Perhaps she was thought too grand for a modest enterprise? ‘But they invited Spessivtseva as a guest artist, and Lopokova, of course. Dolin and Haskell were involved and they knew how hurt Markova was. I don’t get it. Here was this Ballets Russes soloist and they didn’t use her’.

© Tina Sutton. (Click image for larger version)

They did, eventually, just as Ninette de Valois was launching the Vic-Wells ballet with Markova and Dolin as leading dancers. Sutton is intrigued by the relationship between the two. ‘It was the oddest friendship over so many years. Dolin took credit for everything, from her social life to managing her career. He was mean-spirited about her in his books but she never said anything bad about him. He proposed to her a couple of times but she would never accept. They wouldn’t speak to each other but then they’d go on holiday together’.

Sutton thinks Dolin was Machiavellian. ‘To read his letters, you’d believe he was the nicest man, so loving. Then you’d look at the date, at what was happening at the time and what help he wanted from her… he needed her more than she needed him. He tried to make her insecure socially. Yes, he was funnier than her, more of a party person, but I could tell from her diary that she had plenty of dates with friends without him. And she managed the companies they ran together, not him. There are files and files of budgets in her handwriting for costumes, pianists, programmes, publicity on tour. She let him take the credit because she’d say: “How can anyone look at me with any credibility as the disembodied spirit of Giselle if they know I’m a businesswoman?”

Both Markova and Dolin went to the United States when World War II broke out – an apparent defection for which many in Britain never forgave them. But Markova was under contract to impresario to Sol Hurok, needing to earn enough money to support her mother and sisters back in London. ‘She sent frequent care packages to her family and friends and to dancers in England’, says Sutton. ‘The dates and lists of contents are in the back of her diary. She volunteered for charities and she performed for injured American servicemen.’

war-ravaged city where she danced in 100-degree heat with Anton Dolin, 1948.

Picture courtesy Pegasus Books, Markova Archive, Boston University Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center (©)

One of Sutton’s revelations is Markova’s long distance wartime love affair with an Englishman, Stanley Burton, serving in the RAF. She wrote to him longingly while she toured America with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, then with Ballet Theatre. When he eventually married someone else, he returned her letters, which she kept along with everything else – so the record of her lost love is in her archives. ‘They remained good friends’, says Sutton. ‘She used to visit him and his wife when she was in England. She accepted that her career meant the sacrifice of a married life of her own.’

Sutton puzzles over why Markova chose to lead such a relentless life of non-stop travelling to perform into her fifties. ‘She often said “God gave me this talent and I have a responsibility to use it.” Of course in the days before YouTube, she had to be seen dancing worldwide. That way she became the first famous freelance prima ballerina. Pavlova, yes, but she toured with her own company. Markova in her forties guested with other companies all over the world, boosting their reputation as well as her own. She used her fees to fund her next tour to a remote country.’

Sutton insists that Markova wasn’t primarily interested in money. ‘She was publicised as the highest-paid ballerina ever, but she wasn’t rich. She didn’t invest in property, unlike some dancers. She lived in small apartments in New York and London, sharing the Knightsbridge flat with her sisters. She dressed well and she had a mink coat, which kept her warm on tour. But the money she made was spent on touring, on costumes, pointe shoes, hotels, travel, all things that ballerinas had to pay for themselves in those days.’

Picture courtesy Pegasus Books, Markova Archive, Boston University Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center (©)

Medical records in the archive reveal that Markova was often in pain from injuries and illness, with warnings not to dance that she often ignored. ‘She suffered from bouts of bad depression’, Sutton says. ‘There are letters from her sisters saying she had crying jags. I found a private letter in her handwriting on Royal Opera House stationery addressed to “Dear God. I offer you my heartfelt thanks for giving me the power and strength to live and dance through the last two years. [Markova was 47 at the time] … No one will ever know how much I have suffered mentally and physically… there is nothing here on earth to make me feel I want to stay so I am ready to leave at any time”.

Markova carried on dancing for four more years and lived to the age of 94. I remember interviewing her in the Knightsbridge flat above the Scotch House shop. She was very grande dame then, graciously sending her greetings to Sylvie Guillem, who I was interviewing next, from one prima ballerina to another. Tina Sutton’s account of Markova’s ‘hardscrabble’ early years and globe-trotting later ones paints a very different picture of a remarkable woman who battled to establish herself in the eyes of the world. Revealingly, towards the end of her life, Markova said to Vita Paladino (the Gotlieb Archives director), as they drove past Westminster Abbey: ‘They’ll never do a memorial for me.’ They did, with a rabbi in attendance to honour her Jewish faith; and dancers – for the first time in the Abbey – performing roles associated with her.

You must be logged in to post a comment.