© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

Birmingham Royal Ballet

Shadows of War: La Fin du jour, Miracle in the Gorbals, Flowers of the Forest

London, Sadler’s Wells

17 October 2014

www.brb.org.uk

www.sadlerswells.com

The linking theme of Birmingham Royal Ballet’s triple bill of ‘ballets touched in some way by war’, though tenuous, makes for an interestingly contrasted programme. Kenneth MacMillan’s 1979 La Fin du jour is an acid fantasy of pre-WW2 bright young things; Robert Helpmann’s 1944 Miracle in the Gorbals , recreated by Gillian Lynne, is dance theatre in an urban setting; David Bintley’s 1985 Flowers of the Forest romanticises Scotland’s pre-industrial past.

While Bintley’s playful ballet develops into a lament for brave warriors fallen in battle, MacMillan depicted a hedonistic generation oblivious of the carnage to come. His dancers are puppets, manipulated by forces outside themselves. The first sight of them in Ian Spurling’s white box set is of shop-window dummies, twitching like automata. The opening notes of Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major resemble Stravinsky’s motif for the Doll in Petrushka, jerking into action.

© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

The female corps remain anonymous in their fashion-plate outfits; the men, when not required as partners for the two leading women, adopt sporting poses as if for a clothing catalogue. The two principal women (Yvette Knight and Céline Gittens on opening night) are more like hyper-mobile Art Deco figurines than puppets. Their choreography is perversely contradictory, reflecting the changing moods in Ravel’s music. At times they appear bendy and boneless, needing support from as many men as possible; yet their priapic legs are powerful, their feet flexed and pointed like jack knives.

In the languorous second movement they are manoeuvred in aerobatics, smiling complicitly: Knight is sultry, Gittens sparky. They swoop and slide on the music, both aviatrices and lightweight flying machines. The jazzy third movement brings on the cast in fondant-coloured evening dress, as preposterously glamorous as Busby Berkeley chorines. (All credit to Tyrone Singleton for surmounting his oversized beret to cut a dash as a Hollywood hero.) Bright lighting should darken more effectively as the door to the garden is closed at the back of the set. An ominous future waits outside.

© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

Gillian Lynne has added the sound of gunfire to the overture of Arthur Bliss’s score for Miracle in the Gorbals. The ship-building Clyde was a target for German bombers, which is why Michael Benthall, who prepared the ballet’s scenario for Helpmann, had been stationed there at the start of the Second World War. Edward Burra’s frontcloth (recreated by Adam Wiltshire) imagines a vast, looming ship, as bulbous as a missile. Behind it, a huddled mass is about to erupt into a busy street scene as the ballet starts.

Lynne has re-choreographed what Benthall described as a dance-drama. Nobody can now recall the exact steps they danced, though since the set, score and scenario are the same as the originals, Miracle must have been much like this. Its impact is bound to be less, nearly 70 years later, not least because it seems a precursor to The Judas Tree. But it’s a reminder that British ballet dealt with unsavoury subjects well before MacMillan upset his audiences. Burra gleefully recorded Miracle’s first-night reception: ‘You’ve no conception how I enjoyed myself. Everybody was disgusted’.

© Roy Smiljanic. (Click image for larger version)

Lynne’s version is very much an ensemble piece for dance-actors, with the Christ-like Stranger, Helpmann’s own role, less dominant than it was. She sets the Gorbals scene with vivid dance routines reminiscent of her L.S. Lowry ballet, A Simple Man (for Northern Ballet Theatre in 1987). Rather than animated stick figures, however, these are Burra’s Grosz-like slum-dwellers: urchins, old crones, drunkards, layabouts and gossiping women. A scarlet-clad prostitute (Elisha Willis) loiters in a doorway while a laundrywoman hangs out clothes in a tenement across the street. Peter Teigen’s lighting captures the gloomy, sometimes lurid effect of a winter evening in a claustrophobic street.

In contrast to the busy action, an isolated young girl (Delia Mathews) dances a sorrowful solo with deep, yearning backbends to surging strings. Bliss’s score is sympathetically cinematic in the way it describes the characters and their dilemmas. Lynne ensures that nobody is ever alone for long: there can be no privacy in a congested slum. A prominent figure is that of a minister of the cloth (Iain Mackay, handsome and uptight) providing food for a beggar, reprimanding urchins and rescuing a young man from the clutches of the prostitute.

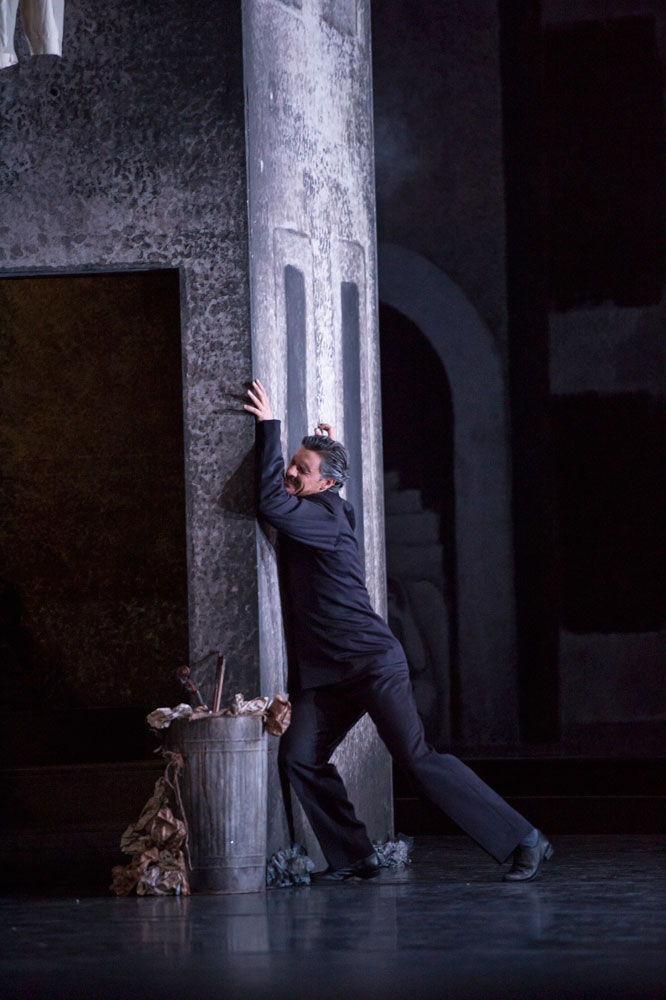

© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

He cannot, however, resuscitate the drowned girl who has committed suicide in the Clyde. A crowd of onlookers forms a Pietà tableau around her lifeless form. They part to reveal the mysterious Stranger (César Morales) in white, who tenderly revives the bewildered girl. The onlookers fling up their arms in Expressionist poses of astonishment. The miracle-worker moves modestly among the inhabitants without appearing mawkishly saintly – Helpmann’s huge hooded eyes must have looked extraordinary in the role.

© Roy Smiljanic. (Click image for larger version)

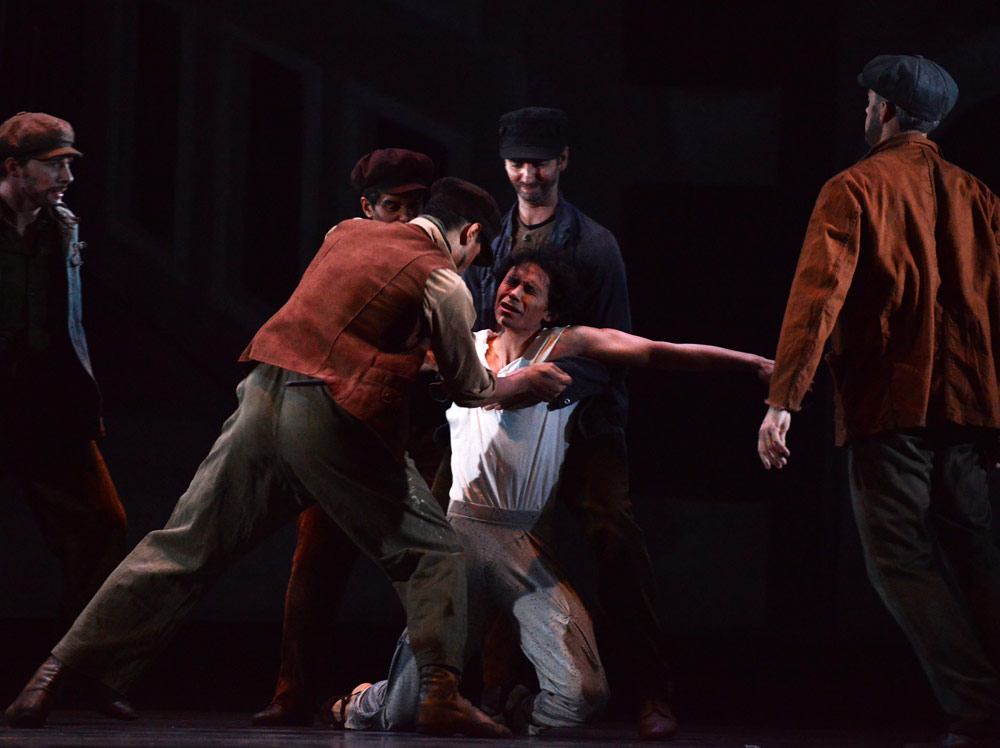

The pious Minister turns out to be no better than anyone else, as he lusts after the prostitute. Willis is impudently brazen as the fallen woman, a welcome break from her good-girl castings. The hypocritical minister, envious of the Stranger, stirs up a vigilante gang who slash the outsider to death. There are seven of them, instead of The Judas Tree’s twelve, but the vicious crowd mentality is the same. Two Marys mourn by the martyr’s body, cradled by the fiddler-beggar (Michael O’Hare): the saved girl and the reformed Magdalen. How widely recognisable is Christian imagery these days, as opposed to the 1940s?

Lynne has made Helpmann and Benthall’s wartime collaboration into a gutsy dramatic ballet, probably with more choreography than Helpmann attempted. Like him, she tells the story admirably clearly, without the need for a synopsis (though BRB’s cast sheet provides one). Although the miracle is supposed to be contemporary, Burra’s designs place it in an era when Glasgow was still an industrial city, so it now has a period feel. I wonder why Lynne didn’t refer more overtly to Scottish dancing, since one reason for its setting was that the tenement-dwellers would have danced socially for their own entertainment. Perhaps she felt there were enough reels in Bintley’s Flowers of the Forest.

© Roy Smiljanic. (Click image for larger version)

Initially inspired by Malcolm Arnold’s Four Scottish Dances, Bintley invented a fleet-footed balletic version of Highland dancing to set his dancers a speedy challenge. The choreography favours the men, their long swirling kilts and flying plaids sweeping across the stage. Nao Sakuma, Arancha Baselga and Maureya Lebowitz were perky and buoyant as the women in the first half, with Elisha Willis elegiac in the second with Mathias Dingman, to Benjamin Britten’s Scottish Ballad.

The change of mood from merry to mournful doesn’t need to be signalled by red lighting across Jon Goodwin’s misty Scottish landscape. The music, based on an old folk tune now used at memorials, accomplishes that effectively enough. A somewhat relentless Highland fling finale, bringing on extra dancers, suggests they might all be reeling on the edge of another abyss – from Flodden Field to modern conflict. The current generation of BRB dancers perform Flowers of the Forest well, relishing the intricate steps Bintley deployed in its creation.

© Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

Two comments on the first night programme at Sadler’s Wells: the interval before Miracle in the Gorbals lasted for 50 minutes, making for a very long evening; however, the two pianists, Jonathan Higgins for Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G and Ross Williams joining him for Britten’s Scottish Ballad were excellent, putting the playing for the Covent Garden company’s Ashton programme to shame.

Correction: I overestimated the length of the interval before ‘Miracle in the Gorbals’. I’ve now checked that it was 40 minutes, due to problems with the set, not 50 – just felt like a very long time.