© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

Baltic Dance Theatre

The Netherlands 2: Body Master, Sarabande, Falling Angels

The Netherlands 1: Clash, Fun, Light

Gdansk, Baltic Opera House

8, 9 November 2014

www.baltyckiteatrtanca.pl

The architecture in the old city of Gdańsk is liberally marked by the style of the Dutch, notably in the proliferation of tall, narrow buildings topped off by a rich variety of curiously-shaped, picturesque gables in streets rippled by colourful facades. This influence reflects the mercantile trading links that constituted the Hanseatic League, an economic confederation of merchants sailing along the coasts of the North and Baltic seas from the 13th to the 17th centuries, and in which Gdańsk (then known as Danzig) was the major market connecting to Prussia and the Eastern Baltic. Four centuries of boat-borne trade from the Netherlands to Danzig – and then up into Riga, Reval (now Tallinn) and Novgorod – has left its mark on the old city, like freckles on the face of a much-loved friend.

This long association with the Dutch has been recognised by a two-day festival of dance, masterminded by Marek Weiss, general and artistic director of the Baltic Opera House, in Gdańsk. The festival is designed not only to reflect this rich history but to recognise the geo-political and cultural similarities of both nations, a statement made possible by the fact that, for long periods in the middle ages and into the modern era, Danzig was a free city state. This mutuality is neatly summarised by Weiss in his written introduction to the festival: ‘The Hanseatic links of our city with the cities of the Netherlands, the love of liberty and the defence of independence from the neighbouring empires, the attention given to civil society values….the ethics of hard work and economic foresight – all of that rhymes in the histories of these coastal lands, so distant geographically, yet so close to one another spiritually’.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

And there is another, more immediate, cultural justification for this association, since the Baltic Dance Theatre – not yet five years old – has taken the Nederlands Dans Theater as its model and adopted Jiří Kylián as its mentor. Kylián was artistic director of NDT for a quarter of a century (retiring in 1999) and he remained its resident choreographer for a further eleven years. BDT’s founding artistic director, Izadora Weiss, trained with Kylián at NDT and in March 2010 she turned that influence to her advantage by exporting a new entity from the Dutch mould, becoming a modern-day equivalent to those hanseatic traders. It may be considered ironic that just as she was bringing a Kylián-based dance influence to Gdańsk, his work was being withdrawn from its spiritual home. But, it appears that Amsterdam’s loss is the rest of the world’s gain since repertoire that was not previously permitted (by NDT) to be performed by other companies is now free to spread like wildfire around the globe.

The Netherlands Festival comprised a back-to-back pair of triple bills, entitled Niderlandy 1 and 2 (although I saw them in reverse numerical order), marrying the existing work of two choreographers long associated with NDT (although one is Czech and the other French) with three “new” works by Weiss herself. The Niderlandy 1 programme had been aired – as a trial run – back in April, but the company counted these November performances as the official premieres.

Although, Weiss’s development as a choreographer has been significantly influenced by Kylián, whom she still reverentially addresses as “maestro”, she has evolved her own unique and powerful brand of choreography. Her movement style is distinctively neoclassical and ever governed by musicality, delivering concepts that are overtly based on narrative, either in terms of an explicit interpretation of literature (she has already tackled Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream and will embark on her third Shakespearian text – The Tempest – in 2015); or by exploring a theme that has been suggested, for example, in a piece of poetry or a work of art (Light is a mixture of both, through Wisława Szymborska’s poem inspired by seeing Vermeer’s painting of The Milkmaid in the Rijksmuseum) or a particular recording: her Rite of Spring is specifically based on Gustavo Dudamel’s conducting of the Orquesta Sinfónica Simón Bolívar; and Fun is the product of her past collaboration with the English violinist and music director, Nigel Kennedy, who has had a home in Poland for many years.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The newest creation came in the very first of the six works seen. Body Master is the latest piece by Weiss and continues her fascination with the power dynamic in master/servant relationships, seen here in a theatrical context and approached with a view to exploring the ironic consequences of changes to the balance of that power. This theatrical concept of the Master, linked to the fact that both Weiss and the other choreographer in this programme (Patrick Delcroix) learned their craft from a man that both refer to as “maestro”, suggested that art might here be imitating life. In every respect, the whole Netherlands weekend could have been sub-titled “Between Master and Pupil”, with Kylián, the master, and Weiss and Delcroix, his pupils, now developing their own artistic trajectories.

Weiss’s self-devised dramaturgy for Body Master is loosely based on the life of Gordon Craig, the English pioneer of modernist theatre who was the son of Dame Ellen Terry and a lover of Isadora Duncan. Craig wrote a cycle of puppet plays and founded a theatre magazine entitled The Marionette, hence the relevance of a puppet character at the beginning and end of the piece. He was also notoriously difficult to work with and although he lived to the grand old age of 94, Craig accomplished little of note after the age of 40.

Filip Michalak captured the contradictions inherent in the “Craig” character, exercising authority over the ensemble of 18 other performers, while at the same time seeking dramatic success from their emotion and artistry. He is eventually supplanted by a new reforming “Master” (Hodei Iriarte Kaperotxipi) who has to relive the same dilemma of how to balance achieving theatrical success by enforcing the creator’s vision with encouraging great performances from his cast. A dichotomy between control and nurture appears to be the work’s defining theme.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

Michalak was a towering presence throughout the unfolding events, a powerful and fluid dancer, combining strength and vulnerability as the narrative’s controlling force. The dénouement of the puppet reviving his comatose body was a remarkable coup de theatre. Two female dancers stood out: Julia Sanz Fernandez, a new recruit to the company, in a tell-tale yellow skirt and white shoes, contrasting with the grey costumes and brown laced boots of the other performers; and Beata Giza, who portrayed the Master’s inquisitive muse with starkly angular athleticism.

The two other pieces in Niderlandy 2 were Kylián creations and the weekend gained an extra frisson since the choreographer oversaw final preparations personally and was present to see the outcome. Kylián doesn’t travel by aeroplane and so his attendance at such premieres is necessarily limited by this constraint. That this was a special occasion was marked by a post-festival banquet hosted by the Dutch Ambassador to Poland who had travelled up from Warsaw for the event.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

Although both are constituents in Kylián’s Black and White series, Sarabande and Falling Angels were created separately (respectively premiering in 1990 and 1989) and the musical accompaniment and casting could not be more diverse: six men perform to Bach’s eponymous music in Sarabande; and eight women dance to the first part of Steve Reich’s Drumming in Falling Angels. And yet a common structural formality coupled with the “Black and White” minimalism in costume and design somehow encourages the works to be conjoined and here they were performed seamlessly, without the separation of a break. As the lighting fades out on the men, the women emerge as upstage silhouettes in an impactful transition.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The casting of both pieces is vital to achieve the patterns, harmonies, synergies and precise timing that both choreographies demand and I must say that the dancers achieved what was required to the extent that I doubt any other group could have bettered. Letting go is a distinct requirement of any Kylián choreography where his brand of dance theatre places an equal emphasis on both elements, with as much stress on expression and gesture (often vocal as well as physical) as on movement. There is no hiding place for inhibition in performances which require meaning in every millisecond and the Baltic dancers responded with an alacrity that was totally integrated across the two groups. The striking contrast of the works is stretched at either end, breaching and mixing gender stereotypes of grace, aggression and emotion.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The dancers appear to have a natural affinity for the strength, athleticism and musicality of Kylián’s work, which must reflect a combination of their artistic director’s own immersion in his style, her motivations when recruiting dancers and the skill of the repetiteurs (Delcroix for Sarabande and Roslyn Anderson for Falling Angels).

Delcroix turned choreographer for the opening work of Niderlandy 1 (the second programme, chronologically). He made Clash, in 2008, for Ballet Junior Genève (a graduate dance company from L’Ecole de Danse de Genève). Originally created for nine women and three men, this new iteration builds on the strength of the male cohort at BDT by doubling that latter number. The women appear first, assembled in diagonal lines of disciplined formation, moving sinuously inside their own personal cylinder of light before being joined by the men, dancing amongst the now stationery women, like Lilliputians playing hide and seek amongst the pegs on a board game. The stage seemed full and I wonder if the impact may not have been stronger with the original casting of just three guys, especially since Delcroix’s sprint-fast, fluid choreography is themed on achieving precise geometric patterns, which must necessarily be changed from his original intentions by these altered proportions.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

Delcroix danced with NDT for 17 years, retiring in 2003, since when he has worked as assistant to Kylián, initially rehearsing his work for NDT and – more recently – staging it on other companies. These influences may be deduced in many elements, not least in the symmetry of movement, changes in tempo and in the strength of association with the music, an eclectic, atmospheric mix of percussion and violins by Murcof (the performing brand of the Mexican musician, Fernando Corona). However, there is nothing remotely derivative about Clash, which has its own trajectory of sequential patterns, entries and exits, which splits into a regenerative process of simultaneous and consecutive duets, sucking dancers from the outer fringes into the central action and closing with a rippling series of three romantic back-to-back duets, which conclude with an emotional and flowing partnership between Michał Łabuś and another new dancer, Naya Monzon Alvarez. There is no let-up in Delcroix’s exhausting choreography, requiring synergised precision timing across the group and the dancers’ tightness in meeting this demand appeared faultless.

Two more premieres by Weiss completed the Niderlandy 1 programme, although Fun and Light had both been seen in April’s test run. The former had been a hastily-contrived addition to what was originally planned as a double bill, utilising part of Hanna Szymczak’s outstanding set construction for Light, providing a wall diagonally stretched across the stage in which a window and wardrobe provide depth, perspective and a hiding place. The strength of Weiss’ achievement in making Fun so quickly is emphasised by it needing no hindsight revision for this full premiere, six months’ later.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

An ongoing theme of the balance (and abuse) of power threads through the narratives that fascinate this choreographer. In this case it is a battle of the sexes that Weiss explores through the rituals of courtship in a “three-into-two-won’t-go” scenario that leaves Sayaka Haruna as the odd-one-out for a haunting final soliloquy to a recording of Julia Fischer playing Paganini’s Caprice. But it seems that Weiss is not showcasing this performer’s isolation for sorrowful reasons, but to emphasise the strength gained from her independence; an ideal enhanced by the self-centred machismo of the two guys (Łabuś and Daniel Flores Pardo). Paulina Wojtkowska and Tura Gómez Coll also reprised their roles from the pilot in April, bringing humour and contrast to an interesting exercise that easily achieved the enjoyment sign-posted by the title.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The opening spectacle of Light, achieved through a winning combination of Szymczak’s designs and Piotr Miszkiewicz’s lighting, provides a remarkably vivid and evocative animation of Vermeer’s painting of The Milkmaid, capturing an arresting theatrical experience of memorable significance. Put simply, the painting comes to life, replicated on stage, with Natalia Madejczyk as the servant, her flame-red hair covered in a white cap, pouring the milk from pitcher into bowl while singing a Dutch lullaby. But, it is not the painting from which Weiss draws her primary inspiration but the poem by Nobel Prize-winning poet, Wisława Szymborska, which asserts that so long as the maid continues to pour the milk, the world will not end.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The painted pouring will never end, frozen forever in Vermeer’s brush-strokes, but in life the actions of his portrait’s subject – the unknown maid – must have come to an end when the jug emptied. And it is from Weiss’ fantasy of what existed outside the famous image and what happened next that the narrative of Light is constructed. As Madejczyk sings and pours, the audience becomes aware that lurking in the dark, just outside the range of the painting, is the master of the house (Michalak again portraying the authority figure). When the milk stops flowing, Szymborska’s warning comes to pass. The master and the maid kiss with devastating – literally house-demolishing – consequences.

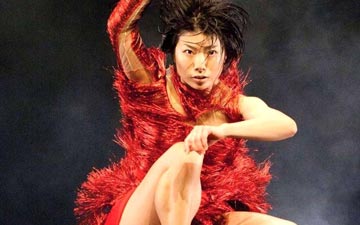

Light is arresting dance theatre that continues Weiss’s predilection for narrative that concentrates on the abuse of power in the master/servant relationship and explores a consequential descent into evil. In addition to the leading performances by Michalak and Madejczyk – who brings both a strength of moral character and a fragile sense of doomed vulnerability to the role of the milkmaid – there are many arresting performances throughout the cast, notably from Giza as the vengeful Mistress, Monzon Alvarez as “the Girl” (a modern-day allegorical victim representing the maid); Haruna and Gómez Coll as the devils unleashed by that kiss, wearing red bikini-tops and shorts; and Łabuś is suitably, vindictively vicious in the guise of ‘The Evil One’. Amongst the quartet of violators, I was struck (as I had been in the corps for Body Master) by the charismatic presence of Beniamin Citkowski (another new recruit for this season).

I admired and enjoyed the concept and visual spectacle of Light, enhanced by the atmospheric choice of music by Philip Glass (Weiss seems to have an unerring ear for just the right music in all her work), and her tactic of developing action simultaneously on two stages (one raised to the side) provides a fascinating perspective in concurrent choreography that reacts in different – but equally rhythmical – ways to the same music. It is an essential ingredient of an undeniably unique style.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

Weiss is well-served by a company of 21 excellent dancers who bring charisma and dramatic expression to the solo roles and cohesive uniformity to the group dancing. In an achievement of remarkable stamina and recall, four dancers (Gómez Coll, Haruna, Łabuś, and Flores Pardo) appeared in five of the six works over the weekend. Given the attention that was naturally focused in rehearsals and preparation for the all-new programme of Niderlandy 2, it was especially impressive that the three works in Niderlandy 1 stood up so well, even exceeding the depth of quality experienced in April’s first run.

It is also worth tipping the cap towards the backstage team at the Baltic Opera House since difficult overnight transitions needed to be achieved in set and lighting requirements. It was undoubtedly an artistic and technical risk to programme six works on consecutive nights but the whole company accomplished this complex challenge with considerable success.

© K. Mystkowski. (Click image for larger version)

The Baltic Dance Theatre now has four of the six Kylián Black and White Ballets in its repertoire since the two new acquisitions performed over this weekend join Six Dances and No More Play, which the company first performed in 2011. On the evidence of how well the company has risen to the challenge of performing these works, I would be surprised if there are not more Kylián classics that follow the hanseatic route to Gdańsk. Petite Mort and Sweet Dreams would complete the Black and White suite and since these particular works also employ minimal sets and costumes, they will be easy to package for export.

While any increase in BDT’s Kylián repertoire is to be welcomed, it is clear that the pupil is now herself becoming a master. Weiss’s bold and imaginative choreography has already established her unique brand of dance theatre through a collection of excellent works that deserve a world audience of their own. The reputation of this nascent company – already significant after just four complete seasons – and their resident choreographer/director must surely continue to grow, reminding us that the trading route does not just end in Gdańsk, but can start there, too.

[Note – the author attended this performance as a guest of the Baltic Opera House]

You must be logged in to post a comment.